Shahram Chubin

- Iran’s nuclear program, initially cancelled after the 1979 revolution, was revived in the closing phases of the 1980-1988 war with Iraq. Tehran wanted to guard against a future surprise analogous to Iraq’s repeated use of chemical weapons.

- Iran has depicted international pressure to suspend its uranium enrichment as a politically motivated attempt to keep it scientifically backward and to deprive its rights under the Nuclear Non Proliferation Treaty.

- Through appeals to nationalism, Tehran has used the prolonged crisis to revive flagging support for the regime and keep the revolutionary faithful mobilized.

- The nuclear issue has long been a proxy for the broader question of how Iran should relate to the world – and whether it should pursue its interests unilaterally or with reference to others’ concerns.

- In a profound sense, the nuclear dispute is now inextricably tied to the political nature of the regime itself.

Overview

One of the central ironies about Iran is that its controversial nuclear program has become a defining political issue, even though many of the program’s details remain shrouded in secrecy. Tehran is public about its quest to acquire peaceful nuclear energy to serve a population that has doubled since the 1979 revolution. But the theocracy vehemently denies any interest in developing a nuclear weapon—even as it boasts about its growing ability to enrich uranium, a capability that can be used to generate power or for a weapons program.

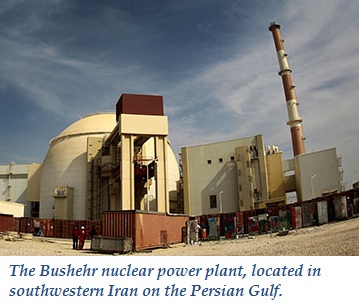

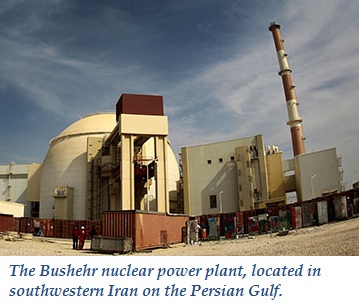

Technically, Iran does not yet need to enrich, since Russia is providing the fuel for the new reactor it built in Bushehr. Tehran counters that it has the right to enrich uranium as a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). It also intends to build additional reactors and says it does not want to be dependent on foreign powers for fuel. But since 2002, international suspicions about Iran’s long-term intentions have deepened because of revelations—by other governments or Iranian exile groups—that it has built secret facilities that could be used for a weapons program. The Islamic Republic has only acknowledged them after the fact.

Iran appears to have wanted to start a secret program for several reasons, from its experience during Iran-Iraq War to the fact that five of the world’s nine nuclear powers are nearby or on its borders. At the same time, it also appears to have adopted a strategy of nuclear hedging—or maintaining the option of a weapons program, while trying to remain within the nuclear treaty. But the disclosures between 2002 and 2009 about its secret facilities and the subsequent international pressure have turned the program into a major political issue at home. In the already tense environment after disputed 2009 presidential elections, Iran’s nuclear program became a political issue that pitted the hardline regime against both conservatives and the Green Movement opposition.

After President Hassan Rouhani took office in 2013, Tehran began more than 18 months of nuclear talks with the world’s six major powers. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei supported the negotiations. But he was careful to balance between reformists and hardliners.

Program’s evolution

Iran’s nuclear weapons program was part of a broader attempt to become more self-reliant in arms and technology in the 1980s. Increasingly isolated, Tehran struggled to acquire arms to fight Iraq, which used chemical weapons and had a nuclear weapons program. The eight-year war was the Middle East’s bloodiest modern conflict. Iran’s nuclear program was an outgrowth of this experience.

The program may also have been a byproduct of the troubled revolution’s omnipresent need for legitimacy and Iranian nationalism’s quest for respect and international status. Tehran has long sought access to nuclear technology generally as a key to development and a means of restoring its former greatness as a center of scientific progress. The theocracy appears to have further dug in its heels because of a perception that the outside world is trying to deny technology and discriminating against a country that—unlike Israel, Pakistan and India—signed the global treaty on non-proliferation. The regime views the international community’s dictates as an attack on a founding principle of the revolution, namely Iran’s independence from outside influence or intervention.

Nuclear politics

Iran’s nuclear program unfolded in context of its overall politics. Since the 1979 revolution, Iran’s political elite has long been divided over how the theocracy should evolve and what international role it should pursue. Beyond broad concepts, such as independence, self-reliance and social justice, consensus has proven elusive—even three decades after the Islamic Republic’s birth. The most fundament difference is whether Iran should continue as a revolutionary state willing to defy the world, or whether it should settle down and become a normal state that plays by international rules. The nuclear issue is increasingly a reflection of this basic division.

Throughout the program’s early stages, there appeared to be a general consensus among the political elite about the need or right to proceed. But by 2005, the consensus appeared to be crumbling. Rival factions in Iran’s political labyrinth began to criticize the nuclear program’s costs and centrality to Iran’s development goals. Iran’s nuclear program had become a domestic political football.

For the public, the nuclear program also initially enjoyed broad popular support since it promised energy independence and scientific progress. It was also popular because the regime depicted it as an assertion of Iran’s rights against foreign arrogance. But the program has not been subjected to informed debate or public discussion about its ultimate goals, the costs, and the relationship with Iran’s other objectives. Consensus ends where specifics begin.

Politics goes nuclear

The nuclear program has evolved through four phases.

Phase one: Period of consensus 1987-2002

The period of maximum consensus on Iran’s nuclear program spanned 15 years. The revival of the shah’s nuclear program was initially presented as necessary to diversify energy sources. Nuclear technology was equated as cutting edge for development and indispensable for any self-respecting power.

But the regime only presented a rationale for energy; it did not acknowledge whatever weapons intentions it had. The program progressed slowly during this phase, as Iran encountered problems of organization and getting access to technology that had to be acquired clandestinely abroad. The United States, already wary of Iran’s weapons intentions, sought to block its access to any nuclear technology. Ironically, the regime may have received a boost from blanket U.S. opposition, which extended to the construction of a light-water reactor at Bushehr that Washington had approved when the shah was in power. Iran’s attempts to evade international opposition—which included purchases from the Pakistan network run by A.Q. Khan—were never discussed domestically.

Phase two: Early controversy 2003-2005

Throughout this period, the nuclear program was largely a concern of Iran’s political elites. The Supreme National Security Council technically acted as the body that reflected all political tendencies. Its decisions therefore allegedly reflected a national consensus.

The 2002 revelation about Iran’s construction of an undeclared enrichment facility at Natanz put Tehran on the defensive. The disclosure coincided with U.S. concern about the spread of weapons of mass destruction to rogue regimes and extremist networks. To avoid exacerbating the issue, the reformist government of President Mohammad Khatami won agreement in the Supreme National Security Council to meet international concerns halfway. Iran agreed to apply the NPT’s Additional Protocol – without ratifying it—which permitted stricter international inspections. It also agreed to voluntarily suspend enrichment for a limited though unspecified time.

Iran’s ensuing negotiations with Britain, France and Germany proved unproductive and added to mutual suspicions. With the U.S. military preoccupied in Iraq, the threat of military action against Iran receded. But hardliners who gained control of Iran’s parliament in 2004 began criticizing reformists for being too soft on the United States for compromising Iran’s interests. In 2005, newly elected President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, backed by Iran’s supreme leader, began enriching uranium again. The deal with the Europeans was dead.

Phase three: Deep divisions 2005-2012

Iran’s nuclear program became increasingly political during this phase. By 2005, both the executive branch and parliament were dominated by hardliners and conservatives. Both Ahmadinejad and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei used the nuclear issue to stigmatize reformists, depicting them as defeatists willing to negotiate away Iran’s interests. Their use of the nuclear issue as an instrument of partisan politics ended the phase when the nuclear program was supposed to be a national issue. And debate was actively discouraged.

Yet the nuclear issue gradually slipped from the hands of the elite to the street. Among hardliners, Ahmadinejad’s populist rallies included frequently orchestrated chants in favor of Iran’s nuclear rights. The president announced that Iran’s nuclear program was “like a train without brakes,” not susceptible to deflection by outside pressure. Slogans, stamps, banknotes and medals became substitutes for informed discussion.

Two factors spurred intense backlash—and a reaction on the other side of the street. First, the United Nations imposed a series of U.N. resolutions between 2006 and 2010 that included punitive sanctions. The United States and the European Union imposed even tougher unilateral sanctions. For the Iranian public, the costs of continued defiance became increasingly clear—and complicated daily life.

Second, Iran’s disputed 2009 election—won by Ahmadinejad amid widespread allegations of fraud—sparked the largest protests against the regime since the 1979 revolution. A new Green Movement opposition was born. Many conservatives also had growing concerns about the populist hardline president, particularly his economic mismanagement. Iran’s new political chasm quickly began to play on the nuclear issue. Four months after the election, Ahmadinejad agreed to a U.S.-backed interim agreement designed to ease tensions and open the way for broader negotiations on Iran’s long-term program. Leaders of the Green Movement as well as key conservatives publicly criticized the deal—reportedly in large part just to oppose Ahmadinejad and prevent him from taking credit for ending tensions with the outside world. Iran soon walked away from the deal.

By 2010, the divide over Iran’s nuclear program had more to do with domestic politics—and very little to do with what many of the key players actually wanted to see happen. Ahmadinejad’s policies produced high inflation, low growth, and massive government corruption. The threat of unrest amplified by the Arab Spring, and reformists’ willingness to play by the political rules instead of outright opposition convinced Khamenei to return to a balance between the two factions – a balance he himself had upset by overtly supporting hardliners since 2005.

By 2012, the greatest threat to the government came not from the United States and calls for regime change, but from popular discontent aggravated by the impact of sanctions.

Phase four: from ‘resistance’ to ‘heroic flexibility’, 2013-2015

In the run-up to the presidential elections of 2013, several candidates criticized the government for not being serious about a diplomatic solution to the nuclear question. President-elect Hassan Rouhani linked the nuclear issue to domestic discontent, stating that Iranians needed more than centrifuges spinning for their well-being.

Khamenei threw his support behind the newly elected pragmatic president, though he was careful to balance between reformists and hardliners.

The Supreme Leader himself risked little. The prime domestic imperative was sanctions relief. If achieved, he could take credit for it. If unsuccessful, he had already laid the groundwork for blaming starry-eyed idealists for the failure.

Factoids

- Iran envisages an energy program that encompasses 10 to 12 reactors generating some 24,000 megawatts and several enrichment plants. It is also building a heavy-water plant at Arak, a source of proliferation concern.

- Bushehr’s 1,000 megawatt light-water reactor was built by Russia and took 15 years to complete. The deal stipulates that fuel is provided by Russia and the spent fuel rods will return to Russia.

- The average reactor takes at least a decade to construct and a minimum of $1 billion before start-up, with costs likely to increase with inflation and international sanctions.

- Even with its own enrichment capability, Iran may lack sufficient indigenous sources of uranium ore.

Major players

Hassan Rouhani, elected president in 2013, took a more pragmatic approach to the nuclear issue than his predecessor Ahmadinejad. Rouhani previously served as Iran’s chief nuclear negotiator under President Mohammad Khatami. Upon taking office, he made it a priority to resolve the dispute with the West over Iran’s nuclear program and end Iran’s diplomatic isolation. On Sept. 27, 2013, Rouhani discussed the nuclear issue with President Barack Obama over the phone – the first direct communication between a U.S. and Iranian president since the 1979 revolution. Iran and the world’s six major powers reached an interim nuclear agreement in November 2013, and Rouhani remained a strong advocate of nuclear diplomacy throughout the months of talks that followed.

Hassan Rouhani, elected president in 2013, took a more pragmatic approach to the nuclear issue than his predecessor Ahmadinejad. Rouhani previously served as Iran’s chief nuclear negotiator under President Mohammad Khatami. Upon taking office, he made it a priority to resolve the dispute with the West over Iran’s nuclear program and end Iran’s diplomatic isolation. On Sept. 27, 2013, Rouhani discussed the nuclear issue with President Barack Obama over the phone – the first direct communication between a U.S. and Iranian president since the 1979 revolution. Iran and the world’s six major powers reached an interim nuclear agreement in November 2013, and Rouhani remained a strong advocate of nuclear diplomacy throughout the months of talks that followed.

Mohammad Javad Zarif was appointed foreign minister in 2013. He has been involved in both formal and informal talks with the United States throughout his career. As Iran’s U.N. ambassador from 2002 to 2007, Zarif attempted to improve relations with the West, including the United States. Zarif speaks English with an American accent after receiving degrees from two U.S. universities. He has played a pivotal role in the nuclear negotiations between Iran and the world’s six major powers. Since the talks began in late 2013, he has frequently met one-on-one with Secretary of State John Kerry. The direct dialogue was a major reversal after three decades of tension with the United States. After a nuclear deal, Zarif would be well-positioned to play a key role in expanding Iran’s outreach to the world.

Mohammad Javad Zarif was appointed foreign minister in 2013. He has been involved in both formal and informal talks with the United States throughout his career. As Iran’s U.N. ambassador from 2002 to 2007, Zarif attempted to improve relations with the West, including the United States. Zarif speaks English with an American accent after receiving degrees from two U.S. universities. He has played a pivotal role in the nuclear negotiations between Iran and the world’s six major powers. Since the talks began in late 2013, he has frequently met one-on-one with Secretary of State John Kerry. The direct dialogue was a major reversal after three decades of tension with the United States. After a nuclear deal, Zarif would be well-positioned to play a key role in expanding Iran’s outreach to the world.

Ali Akbar Salehi is the head of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran. He previously served as President Khatami’s envoy to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) from 1997 to 2005, and President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s foreign minister from 2011 to 2013. He is fluent and English, and holds a PhD from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In March 2015, he joined Iranian negotiators to provide expertise on the technical aspects of the emerging nuclear deal.

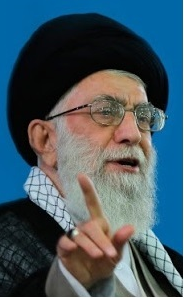

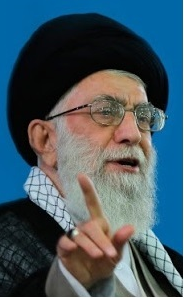

Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei insists that there is an unspecified fatwa against the development of nuclear weapons, but has supported polices that make it impossible to verify this fatwa in practice. Khamenei originally rejected the idea of talks with the United States on the nuclear issue, but indicated openness to negotiations in 2013. In 2014, he issued an infographic outlining his “red lines” in the nuclear talks, in which he defended Iran’s right to a peaceful nuclear program. By April 2015, in the final months before the deadline for a deal, he had expressed his support for a potential agreement. He even defended Zarif and the negotiating team after hardline members of parliament accused negotiators of making too many concessions during the talks.

Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei insists that there is an unspecified fatwa against the development of nuclear weapons, but has supported polices that make it impossible to verify this fatwa in practice. Khamenei originally rejected the idea of talks with the United States on the nuclear issue, but indicated openness to negotiations in 2013. In 2014, he issued an infographic outlining his “red lines” in the nuclear talks, in which he defended Iran’s right to a peaceful nuclear program. By April 2015, in the final months before the deadline for a deal, he had expressed his support for a potential agreement. He even defended Zarif and the negotiating team after hardline members of parliament accused negotiators of making too many concessions during the talks.

Mohsen Rezaie was the Revolutionary Guards commander during the Iran-Iraq War and is known to have told Rafsanjani that Iran could not pursue the war with Iraq to victory without a nuclear weapon. He is now considered a “pragmatic conservative,” and was a presidential candidate in 2009. He suggested an “international consortium” as a possible compromise solution on the enrichment issue. All three of the opposition presidential candidates – Mousavi, Rezaie and former Parliamentary Speaker Mehdi Karroubi – criticized Ahmadinejad’s nuclear policy as provocative and costly for Iran, despite the supreme leader’s explicit support of it. Rezaie ran for president again in 2013, but was defeated by Rouhani. He re-joined the IRGC in April 2015.

Ali Larijani, parliamentary speaker (2008-present) and formerly chief nuclear negotiator (2005-2007), is ambitious and a political opportunist. Larijani started the factionalization of the nuclear issue by accusing the reformists of selling out Iran’s enrichment “pearl” for “candy.” He is a conservative but also had disputes with Ahmadinejad. In 2015, he said it was “the duty of parliament to support the nuclear [negotiation] team,” but also insisted that parliament must approve any additional international protocols to inspect Iran’s nuclear sites.

Ali Larijani, parliamentary speaker (2008-present) and formerly chief nuclear negotiator (2005-2007), is ambitious and a political opportunist. Larijani started the factionalization of the nuclear issue by accusing the reformists of selling out Iran’s enrichment “pearl” for “candy.” He is a conservative but also had disputes with Ahmadinejad. In 2015, he said it was “the duty of parliament to support the nuclear [negotiation] team,” but also insisted that parliament must approve any additional international protocols to inspect Iran’s nuclear sites.

Trendlines

- Iranian support for the nuclear program has always been softer than claimed. Sanctions and low oil prices have done little to strengthen it. The weapons component of the program has never been debated or acknowledged. And further revelations or costs could make it more controversial.

- The success of the nuclear negotiations could lift reformists’ chances in parliamentary elections early in 2016.

- The conclusion of an agreement with the “Great Satan” could establish the precedent that Iran is not always in a zero-sum relationship with the United States – a precedent welcome to reformists but unwelcome to hardliners.

- Iran’s hardline default position to negotiate only under the most severe pressure reinforced a change in the domestic balance of power from 2005 to 2013, making the Revolutionary Guards a principal player in decision-making. The comprehensive nuclear agreement could qualify this change, injecting more moderate voices into the future policies of Iran regionally and domestically.

- By mid-2015, a military strike by the United States or Israel appeared less likely than in earlier years. The final nuclear agreement will need constant, vigilant monitoring - and muscular enforcement if violated. The more turbulent Iran’s domestic politics, the greater the risk that its terms may be violated.

- Iran may find that international acceptance of its de facto right to enrichment has been bought at a very high cost (some estimate over $100 billion) with little in the way of practical benefits.

- Neglected sectors, including the oil infrastructure and the environment - notably water shortages and pollution - should command Iran’s attention in coming years.

Shahram Chubin is a Geneva-based specialist on Iranian politics and a non-resident senior associate of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

This chapter was originally published in 2010, and is updated as of August 2015.

Technically, Iran does not yet need to enrich, since Russia is providing the fuel for the new reactor it built in Bushehr. Tehran counters that it has the right to enrich uranium as a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). It also intends to build additional reactors and says it does not want to be dependent on foreign powers for fuel. But since 2002, international suspicions about Iran’s long-term intentions have deepened because of revelations—by other governments or Iranian exile groups—that it has built secret facilities that could be used for a weapons program. The Islamic Republic has only acknowledged them after the fact.

Technically, Iran does not yet need to enrich, since Russia is providing the fuel for the new reactor it built in Bushehr. Tehran counters that it has the right to enrich uranium as a signatory to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). It also intends to build additional reactors and says it does not want to be dependent on foreign powers for fuel. But since 2002, international suspicions about Iran’s long-term intentions have deepened because of revelations—by other governments or Iranian exile groups—that it has built secret facilities that could be used for a weapons program. The Islamic Republic has only acknowledged them after the fact. Iran’s nuclear weapons program was part of a broader attempt to become more self-reliant in arms and technology in the 1980s. Increasingly isolated, Tehran struggled to acquire arms to fight Iraq, which used chemical weapons and had a nuclear weapons program. The eight-year war was the Middle East’s bloodiest modern conflict. Iran’s nuclear program was an outgrowth of this experience.

Iran’s nuclear weapons program was part of a broader attempt to become more self-reliant in arms and technology in the 1980s. Increasingly isolated, Tehran struggled to acquire arms to fight Iraq, which used chemical weapons and had a nuclear weapons program. The eight-year war was the Middle East’s bloodiest modern conflict. Iran’s nuclear program was an outgrowth of this experience. Hassan Rouhani, elected president in 2013, took a more pragmatic approach to the nuclear issue than his predecessor Ahmadinejad. Rouhani previously served as Iran’s chief nuclear negotiator under President Mohammad Khatami. Upon taking office, he made it a priority to resolve the dispute with the West over Iran’s nuclear program and end Iran’s diplomatic isolation. On Sept. 27, 2013, Rouhani discussed the nuclear issue with President Barack Obama over the phone – the first direct communication between a U.S. and Iranian president since the 1979 revolution. Iran and the world’s six major powers reached an interim nuclear agreement in November 2013, and Rouhani remained a strong advocate of nuclear diplomacy throughout the months of talks that followed.

Hassan Rouhani, elected president in 2013, took a more pragmatic approach to the nuclear issue than his predecessor Ahmadinejad. Rouhani previously served as Iran’s chief nuclear negotiator under President Mohammad Khatami. Upon taking office, he made it a priority to resolve the dispute with the West over Iran’s nuclear program and end Iran’s diplomatic isolation. On Sept. 27, 2013, Rouhani discussed the nuclear issue with President Barack Obama over the phone – the first direct communication between a U.S. and Iranian president since the 1979 revolution. Iran and the world’s six major powers reached an interim nuclear agreement in November 2013, and Rouhani remained a strong advocate of nuclear diplomacy throughout the months of talks that followed.Mohammad Javad Zarif was appointed foreign minister in 2013. He has been involved in both formal and informal talks with the United States throughout his career. As Iran’s U.N. ambassador from 2002 to 2007, Zarif attempted to improve relations with the West, including the United States. Zarif speaks English with an American accent after receiving degrees from two U.S. universities. He has played a pivotal role in the nuclear negotiations between Iran and the world’s six major powers. Since the talks began in late 2013, he has frequently met one-on-one with Secretary of State John Kerry. The direct dialogue was a major reversal after three decades of tension with the United States. After a nuclear deal, Zarif would be well-positioned to play a key role in expanding Iran’s outreach to the world.

Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei insists that there is an unspecified fatwa against the development of nuclear weapons, but has supported polices that make it impossible to verify this fatwa in practice. Khamenei originally rejected the idea of talks with the United States on the nuclear issue, but indicated openness to negotiations in 2013. In 2014, he issued an infographic outlining his “red lines” in the nuclear talks, in which he defended Iran’s right to a peaceful nuclear program. By April 2015, in the final months before the deadline for a deal, he had expressed his support for a potential agreement. He even defended Zarif and the negotiating team after hardline members of parliament accused negotiators of making too many concessions during the talks.

Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei insists that there is an unspecified fatwa against the development of nuclear weapons, but has supported polices that make it impossible to verify this fatwa in practice. Khamenei originally rejected the idea of talks with the United States on the nuclear issue, but indicated openness to negotiations in 2013. In 2014, he issued an infographic outlining his “red lines” in the nuclear talks, in which he defended Iran’s right to a peaceful nuclear program. By April 2015, in the final months before the deadline for a deal, he had expressed his support for a potential agreement. He even defended Zarif and the negotiating team after hardline members of parliament accused negotiators of making too many concessions during the talks. Ali Larijani, parliamentary speaker (2008-present) and formerly chief nuclear negotiator (2005-2007), is ambitious and a political opportunist. Larijani started the factionalization of the nuclear issue by accusing the reformists of selling out Iran’s enrichment “pearl” for “candy.” He is a conservative but also had disputes with Ahmadinejad. In 2015, he said it was “the duty of parliament to support the nuclear [negotiation] team,” but also insisted that parliament must approve any additional international protocols to inspect Iran’s nuclear sites.

Ali Larijani, parliamentary speaker (2008-present) and formerly chief nuclear negotiator (2005-2007), is ambitious and a political opportunist. Larijani started the factionalization of the nuclear issue by accusing the reformists of selling out Iran’s enrichment “pearl” for “candy.” He is a conservative but also had disputes with Ahmadinejad. In 2015, he said it was “the duty of parliament to support the nuclear [negotiation] team,” but also insisted that parliament must approve any additional international protocols to inspect Iran’s nuclear sites.