Iran has emerged as the most influential foreign player in Iraq since U.S.-led forces toppled Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003. Iran and Iraq are Shiite-majority countries that share centuries-deep cultural and religious ties — and a 900-mile border. The Islamic Republic has used these advantages to permeate Iraq’s political, security, economic, and religious spheres.

Iran has capitalized on three pivotal junctures to gain influence in Iraq. The first was the 2003 U.S. invasion, which “constituted a historic opportunity for Iran to expand its influence in Iraq, and to transform it from an enemy into a partner or ally,” according to Michael Eisenstadt. Iran and Iraq fought a bloody war from 1980 to 1988 that produced more than one million casualties. Tehran, haunted by that experience, has worked to ensure that Baghdad will never threaten it again.

Iran has capitalized on three pivotal junctures to gain influence in Iraq. The first was the 2003 U.S. invasion, which “constituted a historic opportunity for Iran to expand its influence in Iraq, and to transform it from an enemy into a partner or ally,” according to Michael Eisenstadt. Iran and Iraq fought a bloody war from 1980 to 1988 that produced more than one million casualties. Tehran, haunted by that experience, has worked to ensure that Baghdad will never threaten it again.

The second juncture was the 2011 withdrawal of U.S. troops. Prime Minister Nouri al Maliki, who was backed by both Iran and the United States, exploited the subsequent security vacuum to move against Sunni leaders. Sunnis deprived of political power, economic inclusion and security were marginalized. Deepening alienation contributed to a resurgence of extremism.

The third juncture was the rise of ISIS in 2014. Tehran rushed to Baghdad’s aid and helped organize new and existing Shiite militias to augment the regular armed forces. “Iranian influence is dominant,” said Hoshyar Zebari, a former Iraqi foreign and finance minister who was ousted in 2016 over corruption allegations. In 2017, he told The New York Times that he lost his position because Iran was suspicious of his connections to the United States.

Since 2014, Iranian officials have made provocative claims about their influence over their western neighbor. In 2014, lawmaker Ali Reza Zakani famously said Iran controlled four Arab capitals —Baghdad, Beirut, Damascus, and Sanaa. “Iraq is not merely a sphere of cultural influence for us,” said Ali Younesi, a senior advisor to Iranian President Hassan Rouhani and a former intelligence minister. In a 2015 speech, he discussed the concept of a “greater Iran” and characterized Iraq as “the center of Iranian heritage, culture, and identity.” Younesi’s comments were criticized by both Iraqi and Iranian politicians, but Iran’s critics saw them as further evidence of Tehran’s alleged expansionist intentions.

Trade and Economy

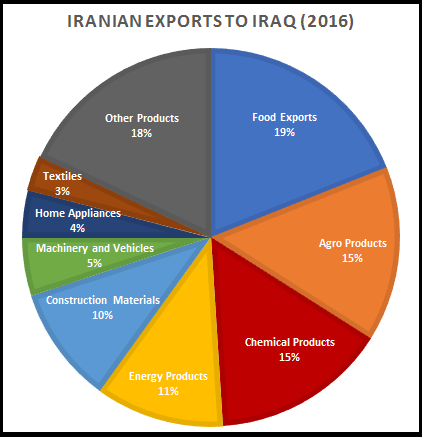

Iran has exported massive quantities of goods to Iraq since 2003. The trade balance has been almost entirely one-sided. “Iran’s exports to Iraq have doubled 17 times over the past decade,” Iran’s trade attaché in Iraq, Mohammad Rezazadeh, said in December 2017. “Iraq doesn’t have anything to offer Iran,” Vahid Gachi, an Iranian official in charge of a border crossing, said in 2017. “Except for oil, Iraq relies on Iran for everything.” Iran’s primary exports have been foodstuffs, liquid fuel, petrochemicals, construction materials, household appliances, and cars.

For years, Iraq’s top trading partners have been Iran, China and Turkey. Their ranks have fluctuated. In 2016, Turkey accounted for 22 percent of Iraq’s foreign trade, followed by China with 20 percent and Iran with 16 percent. Iraq was Iran’s second biggest destination for non-oil exports, after China. “The volume of [annual] trade between Iran and Iraq is around $6.5 and $7 billion, and if we consider other areas like oil, gas, religious tourism, and engineering services it can reach $12 billion,” Naser Behzad, Iran’s Commercial Attaché in Baghdad, said in March 2018.

For years, Iraq’s top trading partners have been Iran, China and Turkey. Their ranks have fluctuated. In 2016, Turkey accounted for 22 percent of Iraq’s foreign trade, followed by China with 20 percent and Iran with 16 percent. Iraq was Iran’s second biggest destination for non-oil exports, after China. “The volume of [annual] trade between Iran and Iraq is around $6.5 and $7 billion, and if we consider other areas like oil, gas, religious tourism, and engineering services it can reach $12 billion,” Naser Behzad, Iran’s Commercial Attaché in Baghdad, said in March 2018.

In March 2018, Iran announced it was ready to open a $3 billion credit line to help with Iraq’s reconstruction. Tehran has shown special interest in infrastructure. Vice President Eshaq Jahangiri stressed the importance of connecting the countries’ rail networks to “give Iraq access to Central Asia and China, and extend Iran’s railway all the way to the Mediterranean Sea.”

Politics

Iran has close ties to Iraq’s major Shiite politicians, many of whom sought asylum in Iran in the early 1980s, during the Iran-Iraq War. They sought support against Hussein’s brutal Sunni-dominated regime. They included:

- The Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI), a political party, was formed in Tehran in 1982 by expatriates; it rebased in Iraq after Saddam’s ouster in 2003. In the 2014 parliamentary elections, it won 29 out of 328 seats.

- The Badr Organization, originally the ISCI militia, split from the parent organization in 2012; it had closer ties to Tehran. In 2014, it entered politics and won 22 seats in parliament. Badr’s leader became transportation minister and another member later became interior minister.

- The Dawa Party was in exile in Iran during the 1980s. It returned to enter politics in 2003. Two prime ministers, Nuri al Maliki and Haidar al Abadi, have come from Dawa. A Dawa-led coalition took 92 seats in the 2014 poll.

- Muqtada al Sadr, a popular Shiite cleric, has had a rocky but sometimes cooperative relationship with Tehran. His militia, the infamous Mahdi Army, received Iranian support and fought both coalition and Iraqi forces in the 2000s. Sadr fled to Iran in 2007. After returning to Iraq in 2011, he distanced himself from Tehran and rebranded himself as a nationalist. But he didn’t sever ties. The Sadrist al Ahrar bloc won 34 seats in 2014.

Iran’s influence with these groups and others have allowed it broker alliances and governing coalitions to ensure that Baghdad would be friendly towards Tehran. The commander of the Revolutionary Guards’ elite Qods Force, Qassem Soleimani, has often played key roles in political negotiations as well as in military operations in Iraq.

Iran has also reportedly tried to directly influence elections by funding and advising its preferred candidates. In March 2018, U.S. Defense Secretary Jim Mattis warned that Iran was using money to sway candidates and votes ahead of parliamentary elections in May. “We know that they are doing what they can to impact the elections, and we don’t like it,” he said.

Not all Shiites have aligned with Iran. Iraqi Vice President Ayad Allawi has been a long-time critic of Iran’s involvement in Iraqi affairs. “Iran has been interfering even in the decision [making process] of the Iraqi people,” he told Reuters in 2017. “We don’t want an election based on sectarianism. We want an inclusive political process ... We hope that the Iraqis would choose themselves without any involvement by any foreign power.”

For decades, Iraq has also maintained close ties with the two major Kurdish parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK). Iran has also cultivated close relationship with both parties and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

Militias

In the 2000s, Iran provided support to several militias—such as the Mahdi Army and its splinter groups, and the Badr Organization—that attacked U.S. and coalition forces. It replicated the Hezbollah model in Iraq—training, equipping, and funding local militias loyal to Iran. Among them is Asaib Ahl al Haq (AAH), founded in 2006 with IRGC support. It has grown into one of Iraq’s most powerful militias and has been politically active since 2011. It now operates a network of political offices, medical clinics and religious schools in Iraq.

.jpg)

After ISIS swept across northern Iraq in 2014, Iran and its Iraqi allies provided critical support to the government when the army collapsed. “We never forget the Islamic Republic of Iran's valuable military and humanitarian aid to Iraq in the fight against the Daesh [ISIS] terrorist group,” Iraqi President and veteran Kurdish politician Fuad Masum told Ali Akbar Velayati, the supreme leader’s top advisor on foreign affairs, in February 2018.

In 2014, dozens of militias—old and new—came together under the umbrella of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF). As of early 2018, the PMF was estimated to have between 100,000 and 150,000 fighters in more than 60 brigades.

The PMF fell under the prime minister’s office, but several Shiite militias have pursued their own interests and worked closely with the IRGC. Some groups have pledged their allegiance to Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The trend has increased concern among Sunnis about the militias’ sectarian nature and their loyalty to Tehran. In 2016, Raad al Dahlaki, a Sunni lawmaker, warned that the PMF could turn into “something that looks like Iran’s Revolutionary Guard.”

Iranian-backed militias have also played politics. The Badr Organization, one of Iran’s oldest allies, won 22 seats in the 2014 election. In early 2018, it seemed poised to capitalize on the military defeat of ISIS in May elections. Hadi al Amiri, the Badr chief, appeared to be a top contender for prime minister; he was running in a coalition of pro-Iran militias. More than 500 militia members or politicians associated with militias were reportedly slated to run.

Religious Ties

Millions of Iranian pilgrims throng to Iraq’s Shiite holy sites in Karbala, Najaf and Samarra annually. More than two million Iranians made the Shiite Arbaeen pilgrimage in fall 2017. The holiday marks the end of 40 days of mourning for the martyrdom of Imam Hussein, who was killed during the Battle of Karbala in 680.

Iran has invested heavily in tourist facilities and infrastructure for pilgrims. In 2014, Soleimani reportedly ordered the construction of a road in Diyala province that would shorten the journey for Shiite pilgrims going to the Golden Dome Mosque in Samarra. The Badr Organization supervised the construction. That road and others through Diyala were helpful for supplying militias fighting ISIS. They also secured Iran’s land connection to Syria and Lebanon.

Iran’s religious influence in Iraq has been stymied, however, by rival schools of Shiite thought. The “quietest” clerics of the holy city of Najaf, Iraq, have largely kept their distance from partisan politics. The most revered among them, Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, an octogenarian with millions of followers globally, has supported Iraqi democracy. The senior clerics of Qom, Iran, have promoted the late Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s principal of velayat-e faqih, or guardianship of the jurist. Iran has promoted its version of clerical rule in Iraq with limited success. The most vocal supporters have been members of Shiite militias funded and trained by Iran. Harakat Hezbollah al Nujaba’s leader, Sheikh Akram al Kaabi, said he would overthrow Iraq’s government if Supreme Leader Khamenei said it was a religious duty.

Culture and Media

In 2003, Iran launched al Alam—a 24-hour Arabic-language television channel with news from the Iranian perspective—to exploit the shifting political landscape. Iran used a terrestrial transmitter near the border to reach people without satellite dishes, so it was one of the first channels to reach Iraqi homes as Saddam’s regime collapsed. Iran’s state media corporation, the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting, runs the station, ensuring its content fits the regime’s view of local and global developments. Other television stations have reportedly been set up with Iranian funding that portray the Islamic Republic Iran as Iraq’s protector.

Garrett Nada is the managing editor of "The Iran Primer" and "The Islamists" websites at the U.S. Institute of Peace.

For more information, see:

Part 2: Pro-Iran Militias in Iraq

Part 3: Iran’s Growing Influence in Iraq

Part 4: Iraq’s Election Leaves Iran’s Influence Intact

Michael Eisenstadt’s chapter in The Iran Primer.