The following series details key aspects of Iran's nuclear program and the ongoing negotiations between Iran and the world's six major powers.

Part 1: ABCs of Issues

Part 2: ABCs of Sites

Part 3: ABCs from Khamenei

Part 4: ABCs of Talks So Far

Iran Nuke Program 1: ABCs of Issues

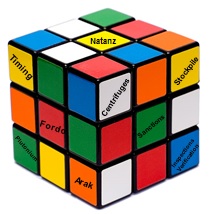

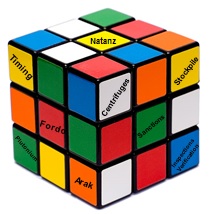

There’s no one single formula for a nuclear deal with Iran. The United States compares negotiations to solving a Rubik’s Cube™, because so many pieces are involved—and moving one moves all the others. (The world’s most popular puzzle has 43 quintillion permutations to solve it so all the colors match on the six faces.) These are some of the key issues in the Rubik’s Cube of a nuclear deal.

There’s no one single formula for a nuclear deal with Iran. The United States compares negotiations to solving a Rubik’s Cube™, because so many pieces are involved—and moving one moves all the others. (The world’s most popular puzzle has 43 quintillion permutations to solve it so all the colors match on the six faces.) These are some of the key issues in the Rubik’s Cube of a nuclear deal.

CENTRIFUGES: Since 2002, Iran has built centrifuges to enrich uranium, which can fuel both peaceful energy and deadly bombs. Tehran claims it is only for medical research and energy. But Iran’s abilities far exceed its current needs; Russia provides fuel for Iran’s single nuclear reactor.

Iran now has about 19,000 centrifuges—up from less than 200 a decade ago. The vast majority of these are first-generation “IR-1” centrifuges, but Iran has begun installing much more sophisticated “IR-2” models. About 10,000 are enriching uranium at Iran’s two enrichment facilities, Natanz and Fordow; the rest are installed but not operating. The more

A deal will try to reduce the number of Iran’s centrifuges. Outside experts suggest the goal could be to limit Iran to between 2,000 and 6,000 operating IR-1 centrifuges, and place constraints on research and development into more advanced machines.

ENRICHMENT: Uranium enriched to 90 percent is the purest form to fuel a weapon. Prior to the November 24 “Joint Plan of Action” (JPOA) interim nuclear deal, Iran was enriching up to 20 percent level; under the JPOA, enrichment has been temporarily capped at five percent or less.

A final deal could seek to limit enrichment to five percent or less.

STOCKPILE: The larger the stockpile of uranium gas, the faster Iran could produce fuel for a bomb. Iran had 447 kg of uranium enriched at 20 percent before the interim deal went into effect in January. It has since begun “neutralizing” its 20 percent stockpile by diluting 104 kg to 3.5 percent enriched uranium and converting another 287 kg into uranium oxide powder. As of May, Iran had an estimated 56 kg of uranium gas enriched at 20 percent. It is due to dilute or oxidize all its 20 percent uranium gas by July 20.

A deal could seek to limit the stockpile of 5 percent enriched uranium and require Iran to further reduce its stockpile of 20 percent uranium in oxide form. Iran may be allowed to keep some for research, but not enough to quickly build a bomb.

NATANZ: Iran’s primary enrichment facility includes three underground buildings, two of which are designed to hold 50,000 centrifuges, and six buildings built above ground.

A deal will try to limit the program at Natanz.

FORDO: The smaller, underground enrichment facility near Qom includes two halls; each could hold 1,500 centrifuges. Iran claims Fordow is to enrich uranium up to 20 percent— only for research. But skeptics contend the deeply-buried site, designed to survive aerial bombardment, is intended to take 20 percent enriched material from Natanz and enrich it to higher levels for use in a nuclear weapon.

A deal will try to end enrichment activities at Fordow, perhaps converting it to a research-only facility.

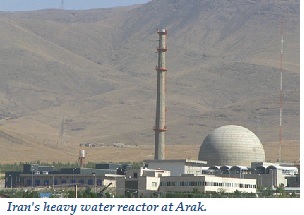

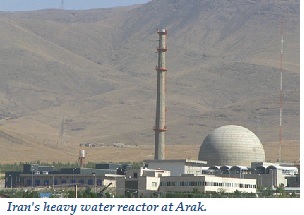

ARAK: The small heavy-water reactor, begun in the 1990s, is unfinished. Iran claims it is to produce medical isotopes and thermal power for civilian use. But the design would also produce plutonium that, if chemically reprocessed, could provide an alternative fuel to uranium for an atomic bomb. Nine kilograms of plutonium is enough material to fuel one or two nuclear weapons. After completion, Arak would need to run for 12 to 18 months to generate that much plutonium.

A deal will try to close Arak or redesign it in a way to substantially reduce plutonium output. A deal will also try prohibit Iran from building a reprocessing facility.

INSPECTIONS and VERIFICATION: Any deal will require considerable transparency into the nature and extent of Iran’s civilian nuclear infrastructure, as well as possible past military dimensions of its program. A deal will also involve extensive inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) of Natanz, Fordow, Arak, centrifuge assembly facilities, uranium mines, research facilities—and possibly other sites—aimed at ensuring that Iran’s program remains solely for peaceful purposes.

It may also cover access to sites suspected of past work on bomb components, such as Parchin military base. And it is likely to require Tehran’s acceptance of the IAEA’s “Additional Protocol,” allowing inspections at both declared and undeclared sites—and maybe other intrusive measures.

IRAN’S RED LINES:

Iran has its own configurations for the Rubik’s Cube of a deal. They include:

- Preserving key elements of its nuclear program, including some uranium enrichment and research and development

-

- Protecting Iran's "right" under the Non-Proliferation Treaty to a peaceful nuclear energy program to alleviate the drain on its oil sources and fuel modern development

- Removing nuclear-related sanctions on Iran by the United States, European Union and United Nations

July 14 Update: Iran released the most detailed report to date explaining its practical needs for its nuclear program. It was posted on the quasi-official website NuclearEnergy.ir.

For more information, see:

Photo credits: Rubik's Cube by by Lars Karlsson (Keqs) (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html), CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/) or CC-BY-SA-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons [edited by Iran Primer], President.ir

Iran Nuke Program 2: ABCs of Sites

The following is a rundown of Iran’s key nuclear sites. Each will be a subject at diplomatic talks between the Islamic Republic and the world's six major powers.

The following is a rundown of Iran’s key nuclear sites. Each will be a subject at diplomatic talks between the Islamic Republic and the world's six major powers.

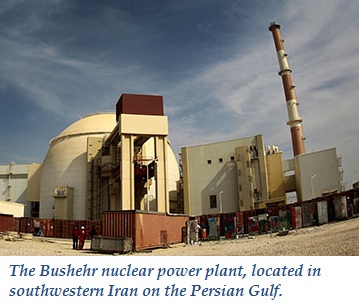

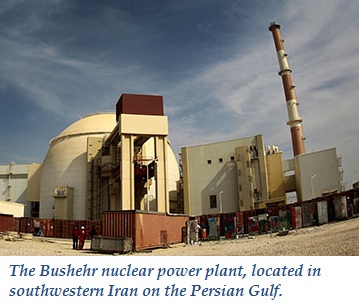

Bushehr Nuclear Facility

The Bushehr facility contains Iran’s first nuclear power plant. Its light-water reactor was loaded with nuclear fuel in August 2010. It has an operating capacity of 1,000 megawatts. Bushehr was originally launched in 1976 under contract with a German company, but after the 1979 revolution, Washington opposed it on the grounds that weapons grade plutonium could be extracted from the reactor’s waste, allowing Iran to construct nuclear weapons. Iran says the plant is for power-generation purposes only and will be subject to International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) safeguards.

The theocracy halted construction of the Bushehr reactor after the 1979 revolution, and it was badly damaged during the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War. But Tehran decided to revive the project in 1990 to provide energy. The contract was awarded to Russia’s Rosatom Corp. To address international concerns, Moscow agreed to supply the enriched uranium fuel for the power plant and take back its plutonium-bearing spent fuel. In February 2005, Tehran and Moscow signed an agreement designed to ensure Iran could not divert enriched uranium for a weapons program. In September 2013, Russia transferred operational control of some key facilities to Iran.

Natanz Fuel Enrichment Facility

This fuel enrichment facility is at the heart of Iran’s dispute with the United Nations. The National Council of Resistance of Iran, an exiled opposition group, revealed the existence of the facility in 2002. It is located just outside the city of Natanz, approximately 130 miles south of Tehran.

The site consists of two facilities:

- An above-ground pilot fuel enrichment plant (PFEP)

- A larger, underground fuel enrichment plant with the capacity to hold up to 50,000 centrifuges (FEP).

Activities at Natanz were suspended in 2004 following an agreement negotiated by Britain, France and Germany. But Iran restarted its uranium enrichment at the FEP after President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s election in 2005. The international community is concerned that Iran may use the enrichment technology at Natanz for nuclear weapons. These activities were proscribed by U.N. Security Council Resolution 1696 in 2006. Iran rejects the legality of these resolutions.

Iran has not installed new centrifuges at either of the Natanz sites since the implementation of the November 2013 Joint Plan of Action. And enrichment of uranium above five percent is no longer taking place at Natanz, according to a February 2014 U.N. report. About 160 kg of uranium enriched to 20 percent still remains at the site but some of the stockpile is being downblended or converted to uranium oxide, which could not easily be used to fuel a nuclear weapon.

Isfahan Uranium Conversion Facility

The historic city of Isfahan is home to several nuclear-related sites, but the most significant facility is the Isfahan Uranium Conversion Plant. Isfahan also has a fuel fabrication laboratory, a uranium chemistry laboratory and a zirconium production plant. The conversion plant has been operational since 2006, and converts uranium yellowcake into uranium hexafluoride (UF6) for Iran's enrichment facilities. The facility can also produce uranium metal and oxides for fuel and other purposes.

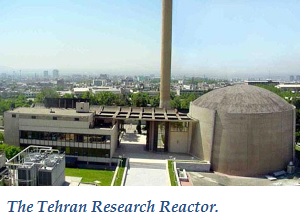

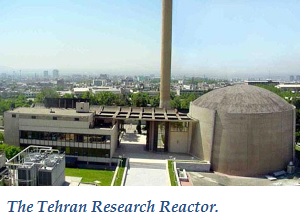

Tehran Nuclear Research Center

The Tehran Nuclear Research Center is a complex of several laboratories, including the Tehran Research Reactor (TRR). The TRR produces radioisotopes for medical and research purposes. The United States supplied Iran with the 5-megawatt light-water reactor in 1967; it was fueled with highly enriched uranium (around 90 percent). In 1987, Argentina concluded a deal with Iran to change the core of the reactor so it could operate on low-enriched uranium (20 percent).

Arak Heavy Water Plant and Reactor

The Arak nuclear facility includes a heavy water production plant, which has been operational since 2006, and a 40-megawatt heavy water reactor still under construction. The National Council of Resistance of Iran, an exiled opposition group, also revealed the existence of this facility in 2002.

Heavy water production plants are not subject to traditional safeguards of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, to which Iran is a signatory. Under the International Atomic Energy Agency’s Additional Protocol, Tehran would be subject to declarations and complementary access for IAEA inspectors. Since Iran has signed but not yet ratified the Additional Protocol, the IAEA uses satellite imagery to monitor the facility. Iran's heavy-water-related activities are also proscribed by U.N. Resolution 1696, which Tehran rejects.

In December 2013, Iran provided the IAEA with information and access to the plant. Approximately 100 tons of reactor-grade heavy water have been produced at Arak since 2006.

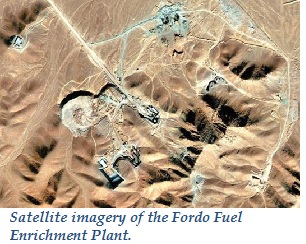

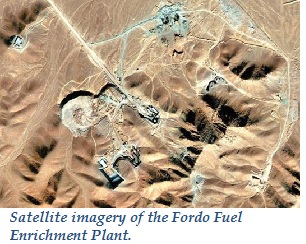

Qom Uranium Enrichment Facility (Fordo)

This secret uranium enrichment facility was made public in 2009 after the United States shared intelligence about it with allies, and Iran confirmed its existence. Construction of the uranium enrichment plant near the holy city of Qom began around 2006, but Tehran maintained that it was not required to report its existence under the safeguard obligations until six months before it became operational. The plant has a few installed centrifuges, but Iran stopped all work once the site was publicized. The facility is located on a mountain on what was reportedly a former Iranian Revolutionary Guards’ missile site.

The facility’s revelation prompted concern that Iran intended to construct a potential breakout facility where it could make weapon-grade uranium for a nuclear bomb. Iran told the IAEA that the plant was intended to enrich uranium only to 5 percent, which is not enough for a nuclear weapon. The plant is believed to have room for 3,000 centrifuges for uranium enrichment.

Parchin

Parchin is a military complex about 19 miles southeast of Tehran. The IAEA suspects Iran may have conducted experiments related to nuclear weapons production. U.N. inspectors visited the site twice in 2005 but did not find anything suspicious. But the IAEA later received additional evidence about alleged experiments. “We didn’t have enough information [back then],” IAEA chief Yukiya Amano

said in 2012. “Extensive activities have taken place” at Parchin that have “seriously undermined” the IAEA’s ability to investigate possible military dimensions of Iran’s program, according to a February 2014

report.

Iran apparently undertook

cleanup activities, according to

satellite imagery analyzed by the Institute for Science and International Security. The IAEA

noted that satellite imagery revealed “possible building material and debris” at Parchin in 2014.

Gchine Mine and Mill

The Gchine mine is located in southern Iran in Bandar Abbas. The associated mill is located at the same site. According to the IAEA, it began production in 2004 and has an estimated production capacity of 21 tons of uranium per year. The IAEA has questioned the mine’s ownership and relationship to Iran’s military. In January 2014, Iran provided the IAEA with managed access to the mine.

July 14 Update: Iran released the most detailed report to date explaining its practical needs for its nuclear program. It was posted on the quasi-official website NuclearEnergy.ir.

Photo credits: NuclearEnergy.ir, Natanz via Iranian President's Office and The New York Times

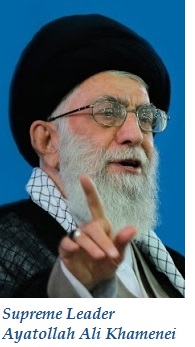

Iran Nuke Program 3: ABCs from Khamenei

Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has voiced his opposition to nuclear weapons on several occasions during the last decade. The following are excerpted remarks in reverse chronological order.

“Even now that reason - including religious and political reason - has made it clear that the Islamic Republic is not after nuclear weapons, American officials bring up the issue of nuclear weapons whenever they address the nuclear issue. This is while they themselves know that not having nuclear weapons is the definite policy of the Islamic Republic of Iran."

April 9, 2014 in a speech to the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran

“We are against nuclear weapons not because of the U.S. or others, but because of our beliefs. And when we say no one should have nuclear weapons, we definitely do not pursue it ourselves either.”

Sept. 17, 2013 in a meeting with Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps commanders

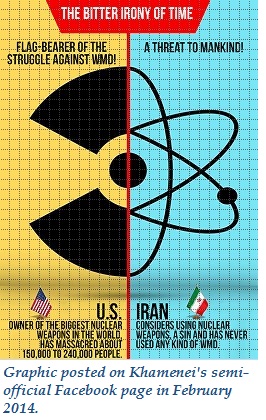

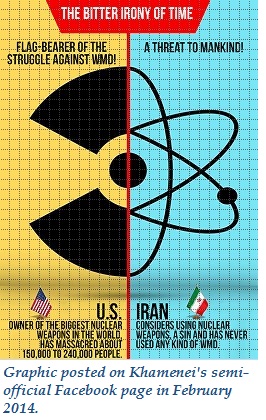

“Nuclear weapons are neither a

#security provider, nor a cause of consolidation of political power but rather a threat to both. The events of the 1990s proved that possessing such weapons would not save any regimes including the Soviet Union. Today as well, we know countries who are faced with fatal torrents of insecurity, despite having nuclear bombs.

“The bitter irony of our time is that the U.S. government has the largest stockpile of nuclear weapons and is the only government that has used them, while it bears the flag of anti-nukes struggle!”

“We do not possess a nuclear weapon and we will not build one, but

we will defend ourselves against any aggression, whether by the U.S. or the Zionist regime, with the same level [of force].”

March 20, 2012 in a speech marking Nowruz, Persian New Year

“Nuclear weapons are not at all beneficial to us. Moreover, from an ideological and fiqhi (juridical) perspective, we consider developing nuclear weapons as unlawful. We consider using such weapons as a big sin. We also believe that keeping such weapons is futile and dangerous, and we will never go after them.”

Feb. 22, 2012 in a speech to nuclear scientists

“Islam is opposed to nuclear weapons and that Tehran is not working to build them.”

February 2010 at a ship-christening ceremony

“The Iranian people and their officials have declared times and again that the nuclear weapon is religiously forbidden in Islam and they do not have such a weapon. But the western countries and America in particular through false propaganda claim that Iran seeks to build nuclear bombs which is totally false and a breach of the legitimate rights of the Iranian nation.”

June 4, 2009 in a speech marking the 20th anniversary of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s death

“Even though the Iranian nation does not have an atomic bomb and keeps no intention to possess the deadly weapon, the world acknowledges that it is a dignified nation because the dignity of the nation has emerged from its resolve, faith, good deed and bright goals.”

Sept. 9, 2007 in a speech to Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps commanders

Iran “is not, and the westerners know it well, after a nuclear weapon, because it stands contrary to the country's political and economic interests as well as Islam's statute.”

Jan. 18, 2006 to Tajik President Imomali Rakhmonov’s visiting delegation

“No sir, we are not seeking to have nuclear weapons… [to] manufacture, possess or use them, that all poses a problem. I have expressed my religious convictions about this, and everyone knows it.”

Nov. 5, 2004 in a Friday sermon

“The Islamic Republic of Iran, based on its fundamental religious and legal beliefs, would never resort to the use of weapons of mass destruction," Khamenei said recently. "In contrast to the propaganda of our enemies, fundamentally we are against any production of weapons of mass destruction in any form.”

July 14 Update: Iran released the most detailed report to date explaining its practical needs for its nuclear program. It was posted on the quasi-official website NuclearEnergy.ir.

Iran Nuke Program 4: ABCs of Talks So Far

The following is a rundown of key events in diplomacy on Iran’s nuclear program since President Hassan Rouhani took office in August 2013.

2013

Sept. 26 –

Sept. 26 – Foreign ministers from P5+1 countries (Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia and the United States) and Iran met on the sidelines of the U.N. General Assembly and agreed to hold a new round of talks in Geneva.

Sept. 27 – President Barack Obama called Iranian President Hassan Rouhani in what was the first direct communication between a U.S. and Iranian presidents since the 1979 revolution. “The two of us discussed our ongoing efforts to reach an agreement over Iran’s nuclear program,” Obama said at a White House briefing.

Oct. 15-16 – Diplomats from P5+1 countries and Iran met in Geneva to solve the nuclear dispute. They committed to meeting in November to continue talks that were “substantive and forward looking.”

Nov. 7-10 – Iran and the P5+1 made significant headway but ultimately failed to finalize an agreement. Foreign ministers rushed to Geneva as a breakthrough appeared imminent. But last-minute differences, reportedly spurred by French demands for tougher terms, blocked a deal.

Nov. 11 – IAEA Director General Yukiya Amano visited Tehran. He and Iran’s chief of the Atomic Energy Organization, Ali Akbar Salehi, signed a Framework for Cooperation Agreement committing Tehran to take practical steps towards transparency within three months.

Nov. 24 –

Nov. 24 – Iran and the P5+1 reached an interim agreement that would significantly constrain Tehran’s nuclear program for six months in exchange for modest sanctions relief. Iran pledged to neutralize its stockpile of near-20 percent enriched uranium, halt enrichment above five percent and stop installing centrifuges. Tehran also committed to halt construction of the Arak heavy water reactor.

Dec. 11 – Iran and the IAEA met in Vienna to review the status of the six actions Iran committed to in November as part of the Framework for Cooperation Agreement.

2014

Jan. 20 – The Joint Plan of Action, the interim nuclear deal, entered into force. The International Atomic Energy Agency reported that Iran reduced stockpile of uranium enriched to 20 percent and halted construction on the heavy water reactor in Arak. The United States and the European Union announced steps to suspend a limited number of sanctions and allow the release of Iran’s oil revenues frozen in other countries.

March 19 –Iran and the six major powers held nuclear negotiations. Ashton and Zarif described their discussions as “substantive and useful.”

April 7-9 –Iran and the major powers met in Vienna for talks on a final nuclear agreement.

April 17 – The U.S. State Department announced steps to release $450 million installment of frozen Iranian funds, after the IAEA verified Tehran was complying with the interim nuclear agreement.

May 13-16 – Iran and the major powers met in Vienna, but the talks ended without tangible progress.

June 9-10 – U.S. Deputy Secretary of State William Burns lead a team of officials to Geneva for bilateral talks with Iran to prepare for the next round of P5+1 talks.

July 3-19 – Iran and the world’s six major powers began marathon talks on July 3, less than three weeks from the deadline. On July 19, the two sides announced an extension through November 24, the one-year anniversary of the interim agreement. Iran agreed to take further steps to decrease its 20 percent enriched uranium stockpile. The major powers agreed to repatriate $2.8 billion in frozen funds to Iran.

July 14 Update: Iran released the most detailed report to date explaining its practical needs for its nuclear program. It was posted on the quasi-official website NuclearEnergy.ir.

Sept. 18-26 – Iran and six major world powers resumed talks in New York. Kerry and Zarif also discussed the threat posed by ISIS.

Oct. 14-16 – Iran and the six major powers made a “little progress” at talks in Vienna.

Nov. 9-11 – Kerry, Zarif, and Ashton met for two days of trilateral talks in Oman, followed by a day of meetings between Iran and all six major powers.

Nov. 19-24 – Iran and six major powers held talks in Vienna. On November 19, the U.S. and Iranian teams held bilateral talks. Kerry, Ashton, and Zarif held another round of discussions on Nov. 21. The two sides missed the November 24 deadline for a deal and announced that talks would be extended until June 30, with the goal of a political agreement by March.

Dec. 17 – Iran and the P5+1 held talks at the deputy level in Geneva. Deputy Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi told reporters that the “intense negotiations” were “very useful and helpful.” No E.U. statement was released after the talks and the U.S. delegation did not provide comments to the press.

2015

Jan. 14, 16 – Kerry and Zarif met in Geneva to find ways to speed up negotiations. They meet again in Paris later in the week.

Jan. 15-17 – Iran and the U.S. hold bilateral talks in Geneva.

Jan. 18 – Iran and the P5+1 powers made limited progress in talks in Geneva. They agreed to meet again in early February.

Feb. 23 – Iran and the P5+1 concluded another round of talks on Iran's controversial nuclear program in Geneva. Atomic Energy Organization chief Ali Akbar Salehi and U.S. Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz joined the talks for the first time to provide technical expertise, but Secretary of State John Kerry noted that their presence was "no indication whatsoever that something is about to be decided."

March 2-5 – Iran and the P5+1 met in Montreux, Switzerland for another round of talks.

March 16-18 – Kerry and Zarif met in Lausanne, Switzerland, and Moniz and Salehi joined the talks to negotiate technical details. Zarif then flew to Brussels to meet with E.U. officials. The Iranian team returned to Switzerland for more talks with U.S. officials on March 17-18.

March 26-30 – Iran and the P5+1 met in Lausanne, Switzerland in the final days before the deadline for a political framework.

Photo Credits: EU External Action Service and U.S. State Department via Flickr

There’s no one single formula for a nuclear deal with Iran. The United States compares negotiations to solving a Rubik’s Cube™, because so many pieces are involved—and moving one moves all the others. (The world’s most popular puzzle has 43 quintillion permutations to solve it so all the colors match on the six faces.) These are some of the key issues in the Rubik’s Cube of a nuclear deal.

There’s no one single formula for a nuclear deal with Iran. The United States compares negotiations to solving a Rubik’s Cube™, because so many pieces are involved—and moving one moves all the others. (The world’s most popular puzzle has 43 quintillion permutations to solve it so all the colors match on the six faces.) These are some of the key issues in the Rubik’s Cube of a nuclear deal. The following is a rundown of Iran’s key nuclear sites. Each will be a subject at diplomatic talks between the Islamic Republic and the world's six major powers.

The following is a rundown of Iran’s key nuclear sites. Each will be a subject at diplomatic talks between the Islamic Republic and the world's six major powers.  The theocracy halted construction of the Bushehr reactor after the 1979 revolution, and it was badly damaged during the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War. But Tehran decided to revive the project in 1990 to provide energy. The contract was awarded to Russia’s Rosatom Corp. To address international concerns, Moscow agreed to supply the enriched uranium fuel for the power plant and take back its plutonium-bearing spent fuel. In February 2005, Tehran and Moscow signed an agreement designed to ensure Iran could not divert enriched uranium for a weapons program. In September 2013, Russia transferred operational control of some key facilities to Iran.

The theocracy halted construction of the Bushehr reactor after the 1979 revolution, and it was badly damaged during the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War. But Tehran decided to revive the project in 1990 to provide energy. The contract was awarded to Russia’s Rosatom Corp. To address international concerns, Moscow agreed to supply the enriched uranium fuel for the power plant and take back its plutonium-bearing spent fuel. In February 2005, Tehran and Moscow signed an agreement designed to ensure Iran could not divert enriched uranium for a weapons program. In September 2013, Russia transferred operational control of some key facilities to Iran. Activities at Natanz were suspended in 2004 following an agreement negotiated by Britain, France and Germany. But Iran restarted its uranium enrichment at the FEP after President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s election in 2005. The international community is concerned that Iran may use the enrichment technology at Natanz for nuclear weapons. These activities were proscribed by U.N. Security Council Resolution 1696 in 2006. Iran rejects the legality of these resolutions.

Activities at Natanz were suspended in 2004 following an agreement negotiated by Britain, France and Germany. But Iran restarted its uranium enrichment at the FEP after President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s election in 2005. The international community is concerned that Iran may use the enrichment technology at Natanz for nuclear weapons. These activities were proscribed by U.N. Security Council Resolution 1696 in 2006. Iran rejects the legality of these resolutions. The Tehran Nuclear Research Center is a complex of several laboratories, including the Tehran Research Reactor (TRR). The TRR produces radioisotopes for medical and research purposes. The United States supplied Iran with the 5-megawatt light-water reactor in 1967; it was fueled with highly enriched uranium (around 90 percent). In 1987, Argentina concluded a deal with Iran to change the core of the reactor so it could operate on low-enriched uranium (20 percent).

The Tehran Nuclear Research Center is a complex of several laboratories, including the Tehran Research Reactor (TRR). The TRR produces radioisotopes for medical and research purposes. The United States supplied Iran with the 5-megawatt light-water reactor in 1967; it was fueled with highly enriched uranium (around 90 percent). In 1987, Argentina concluded a deal with Iran to change the core of the reactor so it could operate on low-enriched uranium (20 percent). Heavy water production plants are not subject to traditional safeguards of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, to which Iran is a signatory. Under the International Atomic Energy Agency’s Additional Protocol, Tehran would be subject to declarations and complementary access for IAEA inspectors. Since Iran has signed but not yet ratified the Additional Protocol, the IAEA uses satellite imagery to monitor the facility. Iran's heavy-water-related activities are also proscribed by U.N. Resolution 1696, which Tehran rejects.

Heavy water production plants are not subject to traditional safeguards of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, to which Iran is a signatory. Under the International Atomic Energy Agency’s Additional Protocol, Tehran would be subject to declarations and complementary access for IAEA inspectors. Since Iran has signed but not yet ratified the Additional Protocol, the IAEA uses satellite imagery to monitor the facility. Iran's heavy-water-related activities are also proscribed by U.N. Resolution 1696, which Tehran rejects. This secret uranium enrichment facility was made public in 2009 after the United States shared intelligence about it with allies, and Iran confirmed its existence. Construction of the uranium enrichment plant near the holy city of Qom began around 2006, but Tehran maintained that it was not required to report its existence under the safeguard obligations until six months before it became operational. The plant has a few installed centrifuges, but Iran stopped all work once the site was publicized. The facility is located on a mountain on what was reportedly a former Iranian Revolutionary Guards’ missile site.

This secret uranium enrichment facility was made public in 2009 after the United States shared intelligence about it with allies, and Iran confirmed its existence. Construction of the uranium enrichment plant near the holy city of Qom began around 2006, but Tehran maintained that it was not required to report its existence under the safeguard obligations until six months before it became operational. The plant has a few installed centrifuges, but Iran stopped all work once the site was publicized. The facility is located on a mountain on what was reportedly a former Iranian Revolutionary Guards’ missile site. “Even now that reason - including religious and political reason - has made it clear that the Islamic Republic is not after nuclear weapons, American officials bring up the issue of nuclear weapons whenever they address the nuclear issue. This is while they themselves know that not having nuclear weapons is the definite policy of the Islamic Republic of Iran."

“Even now that reason - including religious and political reason - has made it clear that the Islamic Republic is not after nuclear weapons, American officials bring up the issue of nuclear weapons whenever they address the nuclear issue. This is while they themselves know that not having nuclear weapons is the definite policy of the Islamic Republic of Iran." “The Iranian people and their officials have declared times and again that the nuclear weapon is religiously forbidden in Islam and they do not have such a weapon. But the western countries and America in particular through false propaganda claim that Iran seeks to build nuclear bombs which is totally false and a breach of the legitimate rights of the Iranian nation.”

“The Iranian people and their officials have declared times and again that the nuclear weapon is religiously forbidden in Islam and they do not have such a weapon. But the western countries and America in particular through false propaganda claim that Iran seeks to build nuclear bombs which is totally false and a breach of the legitimate rights of the Iranian nation.” Sept. 26 – Foreign ministers from P5+1 countries (Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia and the United States) and Iran met on the sidelines of the U.N. General Assembly and agreed to hold a new round of talks in Geneva.

Sept. 26 – Foreign ministers from P5+1 countries (Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia and the United States) and Iran met on the sidelines of the U.N. General Assembly and agreed to hold a new round of talks in Geneva. Nov. 24 – Iran and the P5+1 reached an interim agreement that would significantly constrain Tehran’s nuclear program for six months in exchange for modest sanctions relief. Iran pledged to neutralize its stockpile of near-20 percent enriched uranium, halt enrichment above five percent and stop installing centrifuges. Tehran also committed to halt construction of the Arak heavy water reactor.

Nov. 24 – Iran and the P5+1 reached an interim agreement that would significantly constrain Tehran’s nuclear program for six months in exchange for modest sanctions relief. Iran pledged to neutralize its stockpile of near-20 percent enriched uranium, halt enrichment above five percent and stop installing centrifuges. Tehran also committed to halt construction of the Arak heavy water reactor.