Iran will hold snap elections on June 28, 2024 after the death of President Ebrahim Raisi in a helicopter crash on May 19. The next president will inherit a daunting set of challenges. At home, the unpopular government faced persistent inflation, high unemployment, and discontent over the lack of personal freedoms. Iran was also isolated by Western powers for rampant human rights abuses, an accelerating nuclear program, and arming Russia with drones for the war in Ukraine.

The 2024 election may have longer-term consequences for the Islamic Republic beyond naming a successor to Raisi. The next president could influence the succession process after the death of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who turned 85 in April. Since 1989, Khamenei has had the final say on all major issues. No clear protégé emerged during the first 35 years of his rule. Raisi, a hardline cleric, was thought to be a contender, so his death widened the field of competition. Khamenei was president from 1981 to 1989, when he was chosen to succeed revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the only transition the Islamic Republic has witnessed.

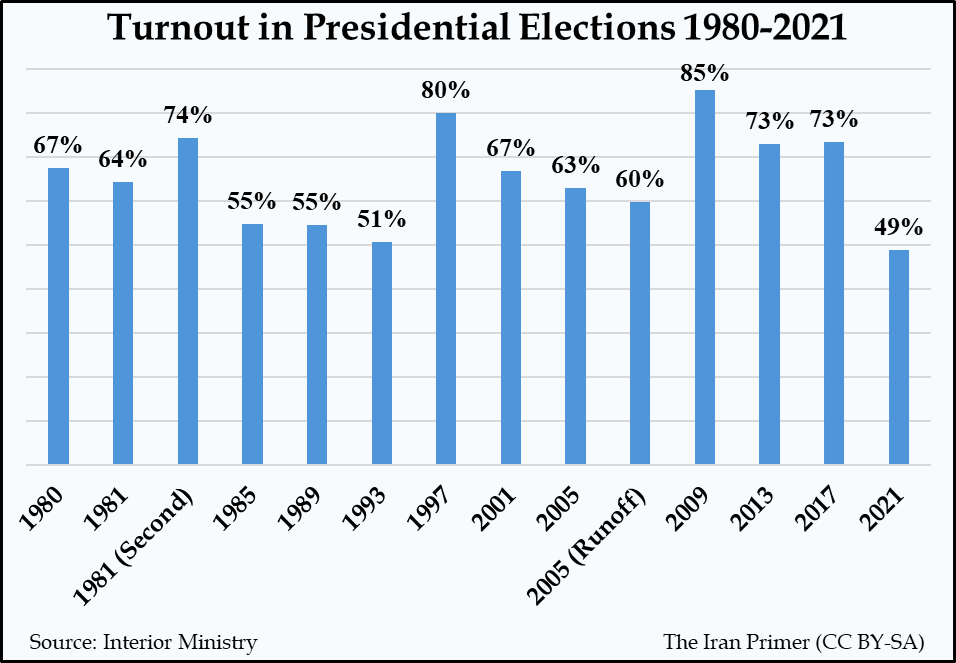

Despite the stakes, many Iranians were expected to avoid the polls. The public was apathetic about elections for Parliament and the Assembly of Experts in March 2024. The turnout was 41 percent, the lowest since the 1979 revolution. In the 2021 presidential election, the turnout, just 48.8 percent, was the lowest for a presidential election in the history of the Islamic Republic. Since 1981, all but one of Iran's presidents have been clerics.

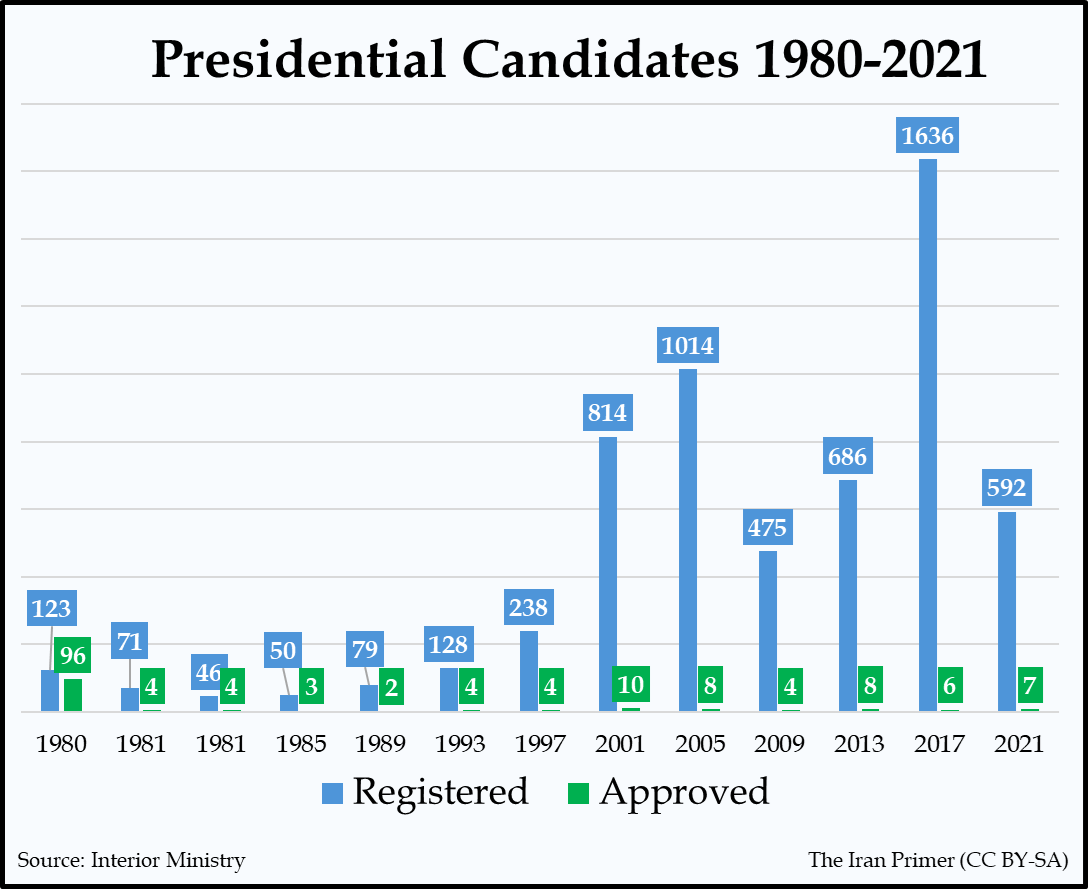

The Guardian Council, a 12-man panel of clerics and jurists, was responsible for vetting all candidates. It has historically limited the number allowed to run. The Guardian Council reviewed the credentials of 80 hopefuls – including hardliners, centrists, reformists, and independents. It approved five conservatives and one reformist:

- Amir Hossein Ghazizadeh Hashemi, a hardliner who served in parliament between 2008 and 2021 and was appointed vice president in 2021

- Saeed Jalili, a hardliner and former secretary of the Supreme National Security Council and chief nuclear negotiator between 2007 and 2013

- Masoud Pezeshkian, a reformist who has been a member of parliament from East Azerbaijan since 2008

- Mostafa Pourmohammadi, a cleric and traditional conservative who served as justice minister, between 2013 and 2017, and was interior minister between 2005 and 2008

- Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf, a traditional conservative who has been speaker of parliament since 2020 and served as mayor of Tehran from 2005 and 2017

- Alireza Zakani, a hardliner who was elected mayor of Tehran in 2021 and was a member of parliament between 2004 and 2016 and again between 2020 and 2021

Ghazizadeh Hashemi and Zakani dropped out on June 27, the day before the election.

Election Schedule

- May 30-June 3: Candidates register to run with the Ministry of Interior.

- June 4-June 10: The Guardian Council review the candidates’ qualifications.

- June 11: The Guardian Council will announce the final slate of candidates. In the past, 10 candidates or less have been qualified.

- June 12-June 26: The campaign period will include five debates on June 17, 20, 21, 24 and 25. The 2009 presidential debates on state-controlled television were the first to be broadcast live in Iran. The 2013 debates were particularly fiery, with candidates lashing out at rivals and charging each other with failing the revolution.

- June 28: On election day, some 61 million people will be eligible to vote.

- July 5: If no candidate wins a majority, more than half of the vote, a runoff will be scheduled.

Trends in Turnout

The regime has long cited turnout as a reflection of public support for the government. Turnout has tended to be high when a diversity of candidates has been approved to run. Turnout was more than 70 percent in the 2013 and 2017 presidential elections in which Hassan Rouhani, who ran on a platform of moderation in both domestic and foreign policy, beat hardliners.

But the government has increasingly narrowed the political space by barring reformists, centrists and even some mainstream conservatives from running for office. It has subsequently struggled to generate public interest in elections. Raisi won the 2021 presidential election with 62 percent of the vote, although the majority did not bother to cast ballots. The turnout, just 48.8 percent, was the lowest for a presidential election in the history of the Islamic Republic. Activists had called for a boycott. Many were frustrated that the Guardian Council had barred candidates who would have been serious competitors. The vetting appeared to be choreographed to give Raisi an easy victory.

Turnout was low in the previous two parliamentary elections as well. In both cases, the Guardian Council barred prominent reformists and centrists. In 2020, 43 percent of voters cast ballots. In 2024, the turnout was 41 percent, the lowest since the 1979 revolution. Only 24 percent turned out in the capital Tehran, according to unofficial results reported by local outlets. The figures reflected widespread dissatisfaction with the government, especially since the bloody crackdown on nationwide protests sparked by the September 2022 death of Mahsa Amini – the young woman arrested by the morality police for an improper head covering – in police custody.

Qualifications to Run

Piety and background: Article 115 of the constitution stipulates the qualifications for presidential candidates: “The President must be elected from among religious and political personalities possessing the following qualifications: Iranian origin; Iranian nationality; administrative capacity and resourcefulness; a good past-record; trustworthiness and piety; convinced belief in the fundamental principles of the Islamic Republic of Iran and the official religion of the country.”

Age, education and experience: Candidates must meet certain requirements to run, including:

- Be between ages 40 and 75

- Hold a master’s degree or equivalent

- Have four years of managerial experience

The body has never cleared more than two percent of presidential candidates to run. In 2024, 80 people from across the political spectrum registered to run. Six were approved.

To be elected, the president must receive more than half the vote. If no candidate wins more than 50 percent, the two top candidates compete in a runoff. Since the 1979 revolution, Iran has only had one runoff. In 2005, Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani won 21 percent and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad won 19 percent. Ahmadinejad won in the runoff with 62 percent of the vote.

In a speech on June 3, 2024, Supreme Leader Khamenei outlined desirable qualities for the next president. “The Iranian nation requires an active, hardworking, knowledgeable, and principled president who believes in the principles of the revolution in order to safeguard their interests and solidify their strategic depth in complex international equations.” Out of the final six approved candidates, Saeed Jalili had the most experience with foreign policy and diplomacy.

During the final days of the 2024 campaign, Khamenei appeared to criticize the lone reformist candidate, Masoud Pezeshkian, who voiced support for the 2015 nuclear deal between Iran and the world's six major powers -- Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia and the United States. “Some politicians in our country believe they must kowtow to this power or that power, and it’s impossible to progress without sticking to famous countries and powers,” he said on June 25. “Some think like that. Or they think that all ways to progress pass through America. No, such people can’t” lead the country well, he added.

Women’s Participation

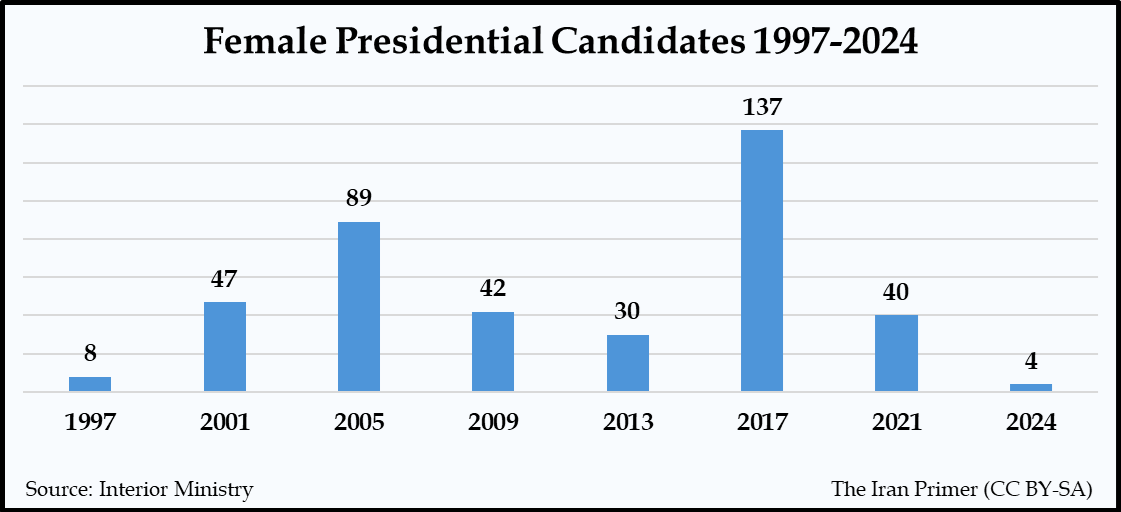

Iran’s 1979 constitution does not specify a gender for the presidency. The Guardian Council has never cited gender as grounds for disqualification, although the 12-man body has also never “qualified” a female candidate. The lack of clarity stems from Article 115 of the constitution, which says the president should be elected from among “religious and political rejal.” In September 2020, Abbas-Ali Kadkhodaei, a Guardian Council spokesman, said that there was no legal prohibition against a woman president. But he added that the body had also not yet ruled on how to interpret the article—or the word rejal, which comes from the Arabic word for men but could also mean “personalities.”

The first woman to register to run, in 1997, was Azam Taleghani, a women’s rights advocate and the daughter of a prominent revolutionary cleric. She registered again in 2009. At age 73 and using a walker, Taleghani registered to run for a third time in 2017. “Women make up 50 percent of the Iranian population, so the country deserves at least one female candidate,” she said. Her goal was to test the intent of Iran’s constitution. “I've come so that the issue with political ‘rejal’ can be resolved,’’ she told the local press when she registered. In 2017, a record number of women—137—registered.

In 2024, four women – all former members of parliament – registered, including: Zohreh Elahian, Hamideh Zarabadi, Hajar Chenarani, and Rafat Bayat. None were cleared to run.

Media Rules

The government published new media regulations ahead of the election that criminalized the publication of content discouraging voting or organizing any unauthorized gathering, including protests. Violators could receive as many as 74 lashes. The guidelines built on guidelines outlined in Clause 74 of the Presidential Election Law:

Article 74- The press and journals are not allowed to publish announcements or texts against candidates in the last three days before the election day; or write texts signifying a group or particular candidate’s withdrawal from candidacy. In any case, candidates have the right to give their response to the newspaper within 18 hours

after the publication through the Ministry of Interior, and the newspaper is charged with the duty to publish the response immediately before the prohibited period according to the press law.In case that publication is not published before the prohibited time, the person in charge [of that publication] must send the candidate’s response to newspapers or journals that appear in the off-period of prohibition out of his/her own pocket. And that publication is obliged to publish it in the first possible issue. Publishing such text in non-press is also forbidden in the three days prior to election day and the objecting candidate has the right to publish his/her opinion prior to the period in which advertisement is prohibited.

Garrett Nada, managing editor of The Iran Primer, assembled this report.