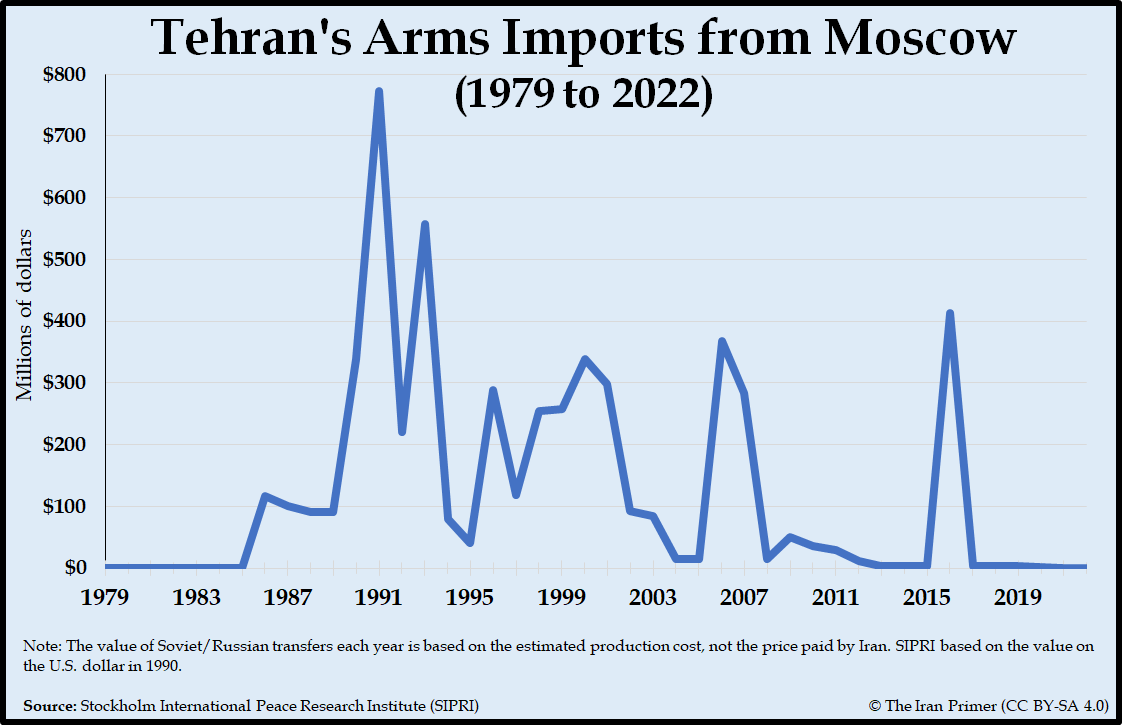

Military cooperation between Iran and Russia has gyrated from virtually nothing after the 1979 revolution to a strategic partnership, bolstered by important arms transfers, by 2023. Overall, Moscow accounted for about a third of Tehran’s arms imports during the four decades after the revolution, according to data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). And the Islamic Republic was exporting Iranian arms to Russia for its invasion of Ukraine. The two countries had forged a “full-scale defense partnership” by mid-2023, according to John Kirby of the National Security Council.

Moscow’s arms transfers to Tehran totaled less than a million dollars in 1979. Tensions between the two nations escalated when Russia armed, aided and supported Iraq during its eight-year war with Iran in the 1980s.

Ties improved after the war ended in 1988 as Tehran began buying Russian warplanes for its decimated air force. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Iran became dependent on Russia for advanced weapons that it could not produce at home and could no longer acquire from the West. By 1991, Russian arms transfers to Iran, including bombers, tanks and submarines, hit an unprecedented $772 million.

But the pace of advanced arms deals dipped between 1995 and 2000 after Moscow and Washington secretly agreed to limit arms sales to Tehran. Russian arms transfers dropped to $15 million in 2005. Transfers spiked again to $368 million in 2006, when Iran finalized purchase of air defense systems as well as warplanes. Arms transfers then dropped to $50 million or less annually between 2008 and 2015. The only major weapons transfer during the next five years was the delivery of the S-300 air defense missile system in 2016.

Yet the quantity of arms belied the nature of military cooperation. The Iranians were often not satisfied with the quality of Russian arms and warplanes–or servicing of the equipment, Farzin Nadimi of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy told The Iran Primer. Russia provided training and parts for repairs. But most technical documents “were never delivered together with the hardware, and Iranians had to compile them from scratch,” he said.

Russian equipment also required “more frequent repairs and overhauls compared to Western examples,” and Iranians were “never happy with the long lead time associated with periodic repairs and overhauls in Russia,” Nadimi added. These issues forced Iran to conduct “major repairs and overhauls in-house for their Russian-made arms and components.” Initially, Iran sent plane engines and three submarines back to Russia for repairs according to original agreements. But by 2012, Iran was able to repair the submarines, procured in the 1990s, without Russian assistance.

Iran instead prioritized self-reliance and developed its domestic arms production capabilities, particularly missiles and drones, amid its international isolation. Tehran advanced to the point where it sought to export weaponry. The Islamic Republic’s defense manufacturing capacity increased 100-fold during the presidency of Hassan Rouhani (2013-2021), claimed Brig. Gen. Hossein Dehghan, then the defense minister. “We’re now not only meeting our domestic needs but can also create opportunities for international markets to export military products to other countries,” he boasted. “The cost and quality” of Iranian weapons allowed Tehran to export to “major countries around the world” despite “unfair sanctions.” For years, Iran had exported missiles, drones and other weapons to proxy militias across the region, including Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, Iraq, and Yemen. By 2023, Iran had exported more than a thousand drones to Russia in addition to artillery and tank ammunition for the war in Ukraine.

Related Material: Timeline: Iran-Russia Collaboration on Drones

Between 1979 and 2023, Russia and Iran did not carry out joint military missions but they did share military intelligence for operations in the Middle East. Iran, Russia, Syria, and Iraq established a joint intelligence center in Baghdad in 2015 to coordinate their separate operations against the ISIS caliphate that had seized a third of both Iraq and Syria. In Syria, Iran allowed Russian warplanes to take off from the western Hamedan Airbase to strike ISIS targets in 2016.

Between 2010 and 2023, Russia and Iran carried out nine joint military exercises focused largely on terrorism, piracy, and search-and-rescue missions. A six-day drill in 2020, held in southern Russia, included 80,000 troops and observers from at least 12 countries, mostly from Russia. The exercise simulated a terrorist incursion with responses by ground, sea and air forces. Iran participated mainly in the naval operation. Beginning in 2019, Iran, Russia and China held annual naval drills in either the Indian Ocean or near the Gulf of Oman. Both the Revolutionary Guards and Iran’s conventional military usually participated.

By 2023, Iran-Russia relations had “come a long way,” Nadimi said. Tehran was “very hopeful to establish meaningful military and security relations” with Moscow, he added. “But so far they have not been successful at all.” Bilateral military exercises were “very limited in scope and objectives.”

Phase One: 1979 to 1988

After Iran’s 1979 revolution, the Soviet Union explored military ties with the new Islamic government. But relations soured after Iran’s hardline theocrats purged members of the communist Tudeh Party from the young theocracy. Soviet arms sales to Tehran were limited during the 1980-1988 Gulf War as Moscow backed Baghdad militarily. Over eight years, Russia reportedly sold Iraq at least $30 billion in arms, but sold only $1.5 billion in military equipment to Iran. Russia ramped up military support after Iran broke through Iraqi lines, split Iraq’s forces and captured Iraqi territory. Moscow became Iraq’s largest source of arms for the duration of the war.

Phase Two: 1989 to 1994

Iran turned to Moscow to restock and rebuild its decimated military after the war ended in 1988. During a 1989 trip to Moscow, Speaker of Parliament Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani secured a commitment to “bolster the military capacity of the Islamic Republic.” Tehran received nearly $1.9 billion in equipment including warplanes–both fighters and bombers–as well as tanks and submarines from Moscow between 1990 and 1993.

Phase Three: 1995 to 1999

Military sales and cooperation dissipated in the mid-1990s after Russia and the United States signed a secret agreement not to forge new arms deals with Iran. The deal required Russia to cease new arms sales to Iran in exchange for a U.S. pledge not to impose sanctions on Moscow. Russia, however, was allowed to complete outstanding orders of military goods, including tanks and a submarine, by the end of 1999.

Phase Four: 1999 to 2009

Vladimir Putin, elected to the presidency in 2000, publicly reneged on the deal brokered between former President Boris Yeltsin and the Clinton administration. Russia’s decision to resume defense cooperation with Iran reflected its pivot away from the West, which had defined the post-Soviet period in the 1990s.

Tehran only made two major purchases from Russia–air defense systems and Su-25 ground attack aircraft–between 2000 and 2006. Over the next three years, international concern grew over advances in Iran’s nuclear program, including a covert facility at Fordow in the mountains outside the holy city of Qom, to enrich uranium. It was disclosed by U.S. and European intelligence. In 2006, a new U.N. Security Council resolution prohibited all nations, companies and individuals from sending Iran goods or technology related to nuclear weapons and delivery systems for the bomb. The resolution called on U.N. member states to freeze the assets of 22 corporations and individuals involved in Iran’s nuclear or ballistic missile programs. Russia refrained from major arms sales to Iran.

Phase Five: 2010 to 2015

In 2010, Russia backed U.N. Security Council resolution 1929 that imposed sweeping sanctions on Iran, including a ban on the transfer of most conventional weapons. Russian arms transfers to Iran declined from $35 million in 2010 to $4 million in 2015. In 2011, Tehran sued Moscow in the International Court of Justice in Geneva for breach of contract after Russia failed to deliver the S-300 air defense system. Iran had already paid $166 million for the S-300s which cost $800 million. Three years of international pressure forced Iran to the negotiating table with the world’s six major powers in 2013. After two years of intense diplomacy, they announced the landmark Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)–which eased sanctions in exchange for limitations on Iran’s nuclear program–in mid-2015.

Phase Six: 2016 to 2021

Implementation of the JCPOA began in January 2016. Arms transfers surged in 2016, as Russia fulfilled the long-delayed order, dating back to 2007, for the S-300 air defense missile system. Iran’s arms imports from Russia totaled $413 in 2016, but then dropped to around $3 million or less for four years through 2020. The expiration of the U.N. conventional arms embargo in 2020 did not lead to a significant uptick in arms imports in 2021 in part because Iran’s domestic arms industry had become more self-sufficient. Iran had developed an increasingly advanced arsenal of ballistic missiles as well as drones for surveillance, reconnaissance and combat. Officials sought to export arms as a new source of revenue amid U.S. sanctions.

Phase Seven: 2022-

Iran and Russia developed a new and unprecedented strategic alliance after Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. In a reversal of roles, Russia turned to Iran to acquire arms. Between August and December 2022, Iran provided hundreds of reconnaissance and suicide drones that Russia deployed against both government and civilian targets, the United States claimed. Dozens of Revolutionary Guards were reportedly deployed in occupied Crimea to train their Russian counterparts. Iranian-made drones were linked to the deaths of hundreds of civilians, including children, by the end of 2022. Tehran also shipped artillery and tank rounds to Moscow. Iran quickly became Russia’s top military backer. “Iran sees a humiliating Russian defeat in Ukraine as a defeat of its own,” Nadimi said. “Strategically, they are very connected.”

In exchange, Tehran sought Russian fighter jets, attack helicopters, radars, and combat trainer aircraft worth billions of dollars. Iranian pilots reportedly started training in Russia on the Sukhoi Su-35, an advanced fighter jet, in the spring of 2022. The Su-35 “would significantly strengthen Iran's air force relative to its regional neighbors,” John Kirby of the National Security Council warned in December 2022. On the first anniversary of Russia’s invasion, Kirby said Moscow was providing Iran “unprecedented defense cooperation, including on missiles, electronics and air defense. Russia had reportedly provided Iran with captured Western arms – including British and U.S. anti-tank and anti-aircraft missiles – for potential reverse-engineering. The following are timelines of major arms transfers and exercises.

Timeline of Arms Transfers

1986: The Soviet Union sent Iran 400 Strela-2s, shoulder-fired surface-to-air missile systems.

1986-1987: Iran purchased more than 200 BTR-60 armored personnel carriers from the Soviets.

1986-1989: Russia sent Iran 400 BMP-1s, a lightweight infantry fighting vehicle.

1989: Iran purchased 25 MiG-29s from the Soviet Union. The first 14 were delivered in 1990 while the final 11 were delivered in 1991.

1989: Iran ordered 100 R-27 missiles from the Soviet Union, an air-to-air missile commonly installed on MiG aircraft.

1989: Iran ordered 400 R-60 air-to-air missiles from the Soviet Union, commonly installed on MiG-29 and Su-24 combat aircraft.

1989: Iran ordered 300 R-73 short-range Soviet air-to-air missiles.

1989: Iran purchased 42 S-200 air defense systems from the Soviet Union.

1990-1991: Iran received 25 MiG-29 fighters and 12 Su-24 tactical bombers from the Soviet Union. The MiG-29 entered Soviet service in the early 1980s, and the Su-24 entered service in the mid-1970s. The MiG-29, a versatile craft, remained Iran’s most advanced fighter as of mid-2023.

1991-1993: Iran concluded a deal with the Soviet Union to purchase two Kilo-class submarines, delivered by Russia after the breakup of the USSR. The Kilo is a diesel-powered submarine capable of traveling 400 nautical miles while submerged. The Kilo entered Soviet service in the mid-1980s and was manufactured until the 1990s.

1991: Iran signed a deal with Russia to domestically produce T-72 tanks and BMP-2 armored personnel carriers.

1993-2001: Russia sent Iran more than 400 BMP-2s, lightweight infantry fighting vehicles.

1993-2001: Iran received up to 422 T-72 tanks from Russia. The T-72 entered Russian service in 1969 and was used by Russian forces in Ukraine as of 2023.

1996: Iran received an additional Kilo-class submarine from Russia.

2000-2003: Iran received more than 40 Mi-8/Mi-17 helicopters from Russia.

2006: Iran reportedly purchased up to six Su-25s from Russia. The Su-25 is a single-seat ground attack aircraft manufactured between 1978 to 2017.

2006-2007: Iran received 29 Tor-M1 air-defense missile systems and over 700 missiles for the system. The Tor-M1 was a short-range mobile air defense system.

2016: Russia sold S-300 air defense systems to Iran. The S-300 was a long-range surface-to-air missile system produced between 1975 and 2011.

Jul. 11, 2022: White House National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan revealed that Iran was preparing to provide Russia with “up to several hundred” drones for use in the war on Ukraine.

Aug. 5, 2022: Iran had transferred 46 UAVs, including Shahed-129s, to Russia for use against Ukraine, said Oleksiy Arestovych, a Ukrainian presidential advisor.

Aug. 19, 2022: Russian cargo planes carrying at least three types of Iranian drones – the Shahed-129, the Shahed-191 and the Mohajer-6 – departed Tehran. All three can carry out reconnaissance and attack missions.

Aug. 20, 2022: A Russian military aircraft flew to Tehran with:

- $145 million in cash

- a British NLAW anti-tank missile

- a U.S. Javelin anti-tank missile

- a U.S. Stinger anti-aircraft missile

The British and American munitions were in a shipment originally meant for Ukraine, according to Sky News. But Russia intercepted the munitions. In return, Iran provided Russia with 160 UAVs, including 100 Shahed-136 suicide drones.

Oct. 14, 2022: Iran dispatched dozens Revolutionary Guards specialists to eastern and southern Ukraine to train the Russian military on drones.

Nov. 9, 2022: Iran and Russia reportedly signed a deal to manufacture drones in Russia. President Raisi said that Iran and Russia were upgrading bilateral relations to counter U.S. sanctions on both countries. Head of the Supreme National Security Council Ali Shamkhani said that Iran was willing to negotiate an end to the war. “Iran welcomes and supports any initiative that would lead to a ceasefire and peace between Russia and Ukraine.”

Dec. 9, 2022: Iran had become Russia’s “top military backer,” John Kirby of the National Security Council claimed. “In exchange, Russia is offering Iran an unprecedented level of military and technical support.” Moscow may also plan to provide Tehran with helicopters and air defense systems “within the next year.” Iranian pilots reportedly started training in Russia to fly the Sukhoi Su-35, an advanced fighter jet, in the spring of 2022.

May 9, 2023: The United States revealed that Iran was supporting Russian efforts to build a drone factory hundreds of miles east of Moscow. The factory could start producing drones in 2024, according to John Kirby of the National Security Council. Tehran was reportedly providing materials for the facility, which would enable Russia to manufacture its own drone supply rather than importing drones from Iran via the Caspian Sea. The Islamic Republic sought fighter jets, attack helicopters, air defense systems, military radars, and other equipment, worth “billions of dollars,” from Russia, Kirby said. “This is a full-scale defense partnership that is harmful to Ukraine, to Iran’s neighbors and to the international community.”

Sept. 2, 2023: Iran had received at least two Yak-130 trainer jets from Russia, according to Iranian media. The trainer craft—which could be used for combat—were reportedly held by the Air Force in Isfahan province. Iranian outlet ISNA added that the aircraft would train pilots to fly more advanced fighter jets.

Timeline of Joint Military Exercises

October 2014: Russian and Iranian warships conducted a joint exercise in the Caspian Sea. Ships from Russia’s Caspian Flotilla joined the Iranian ships at Iran's Anzali port, and then departed for a joint exercise with Kazakhstan.

August 2015: Two Russian warships participated in a three day joint-exercise with Iranian ships on the Caspian Sea. Iranian officials reported that the exercise included 200 Iranian and 150 Russian sailors. The exercise reportedly focused on expanding mutual cooperation and raising combat readiness.

July 2017: Iranian and Russian ships conducted a joint exercise as part of a three-day Russian visit in Iran.

October 2017: An Iranian flotilla joined Russian ships to conduct a three-day exercise in the Caspian Sea.

December 2019: Iran, Russia, and China held their first joint naval exercise, dubbed “Maritime Security Belt.” The three countries were “preparing naval drills for fighting terrorists and pirates in this part of the Indian Ocean,” Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said. Iran’s Rear Admiral Gholamreza Tahani said that the exercise showed that “Iran cannot be isolated.” Forces from Iran’s conventional navy and the Revolutionary Guards participated. The naval forces held shooting exercises and practiced rescuing ships under attack or on fire.

September 2020: A six-day drill, “Kavkaz 2020,” was held in southern Russia. It included 80,000 troops and observers from at least 12 countries, mostly from Russia. The exercise simulated a terrorist incursion with responses by ground, sea and air forces. Iran participated mainly in the naval operation.

February 2021: Iranian and Russian ships participated in the second “Maritime Security Belt” exercise in the Indian Ocean. The Chinese Navy did not join the exercise. “The purposes of this drill are to enhance the security of international maritime trade, confront maritime piracy and terrorism, and exchange information,” said Iranian Rear Admiral Gholamreza Tahani. The exercise covered 17,000 square kilometers of sea, and included operations such as rescuing a burning vessel, freeing a hijacked ship, and target shooting.

January 2022: Iran, Russia, and China held a third iteration of the “Maritime Security Belt” joint-naval drill in the Indian Ocean. “The purpose of this drill is to strengthen security and its foundations in the region, and to expand multilateral cooperation between the three countries to jointly support world peace, maritime security and create a maritime community with a common future,” said the drill’s spokesperson, Iranian Rear Admiral Mostafa Tajoldini. The three countries conducted drills which included rescuing a hijacked ship and night live-fire exercises.

March 2023: Iran, Russia, and China held the fourth “Maritime Security Belt” joint naval drill in the Gulf of Oman. The goal was to deepen “the practical cooperation among the navies of the participating countries, further demonstrate their willingness and ability to jointly protect maritime security, actively build a maritime community with a shared future, and inject a positive momentum to the regional peace and stability," said the Chinese Defense Ministry in a statement. A Chinese Type 052D guided-missile destroyer participated in the exercise. The drills included joint maneuvers and live-fire exercises.

Picture Credits: Mohajer-6 via Mehr News Agency CC BY 4.0; Mig-29 via Mehr News Agency CC BY 4.0; S-300 via Tasnim News Agency CC BY 4.0; S-200 via Tasnim News Agency CC BY 4.0; T-72 via Tasnim News Agency CC BY 4.0; Sailors boarding a ship via Mehr News Agency CC BY 4.0