When did Iran start building a drone fleet?

Iran’s interest in drones and uninhabited vehicles really goes back to the Iran-Iraq war in the mid-1980s. The Iranians have been in the unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) business for several decades. The first generation of the Ababil that was used during the Iran-Iraq war appears to have been a low-cost attack munition, rather than an intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) platform.

Why did it build a drone fleet?

There are a number of reasons why Iran became interested in UAVs. During the Iran-Iraq war, air power was important but the attrition rates for crewed combat aircraft were high. The UAVs let Iran fill some of these roles with a much cheaper, much easier to manufacture capability. Both cost and the technology allowed Iran to go down this path. It imported some technologies as well in the early days. UAVs filled roles that Iran’s air force otherwise might not be able to meet at an acceptable loss-rate of aircraft.

What UAVs allow Tehran to do—compared to a crewed combat aircraft—is mitigate the risk of loss. For example, UAVs can be flown much closer to the opposition forces and take imagery. If the drone gets shot down, then Tehran has lost the equivalent of a small, ‘radio-controlled’ aircraft. Iran doesn’t have to worry about getting the crew back. If they lose a pilot or crew downed in hostile territory, it becomes an issue. That just isn't the case with UAVs. They are also much cheaper than manned aircraft, at least at the low-end of the capability spectrum.

What types of drones are in Iran’s fleet?

Iran’s systems range from small, lightweight short-range systems all the way up through medium-to-heavy UAVs in the intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance roles (ISR). Not only has the portfolio grown in terms of the breadth of capabilities, but also the size of the vehicles themselves has grown. The larger the UAV, in relative terms, then the greater the payload. Iranian systems can be fitted with a variety of electro-optical sensors and weapons.

How did Iran acquire UAVs?

There are, broadly speaking, two entry points for acquiring UAVs. One route is to already possess an advanced aerospace research and development and technology base. The United States and Israel, which were early adopters, both already had capable defense aerospace industries, that could develop high-end unmanned systems. Both countries developed high-end and or medium-to-high end capabilities comparatively early. In Iran's case, it was the other way around. Iran came in with a pretty low initial capability, but UAVs were something they could either acquire or develop internally.

How does Iran use its drones?

Iran has a dual-track approach. Within the conventional military, UAVs fulfill traditional operational roles—such as intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance—at a variety of ranges depending on the vehicle and the sensors on board. Some of the UAVs also carry weapons. Many of Iran’s UAVs seem to be operated by the Revolutionary Guards (IRGC), although the conventional Army and Navy have also deployed drones. The IRGC also reportedly provides these systems, along with the design and manufacturing skills, to its regional proxies, which offers Iran plausible or perhaps implausible deniability about links to any attack source. The Houthis in Yemen, Hamas in Gaza, and Popular Mobilization Forces in Iraq all field UAVs or direct attack munitions (also known as suicide or kamikaze drones) that have an Iranian fingerprint.

What percentage are purchased? What percentage (roughly) are manufactured domestically?

During the 1980s and into the 1990s, Tehran benefitted from defense cooperation with China, including the purchase of a variety of mainly anti-ship missile systems. It is possible, if not likely, that Iran may have been influenced during this period by Chinese designs. Some early Iranian drones have a "Chinese look" about them.

As Iran developed and grew its UAV portfolio, the vast majority were produced at home. The current fleet is overwhelmingly domestically manufactured. Some components may have been acquired in the gray market or were acquired covertly. There are indications in U.N. reports that this remains the case. But in terms of the overall design, manufacturing is now done inside Iran.

How many of Iran’s drones are based on models they have downed and/or copied?

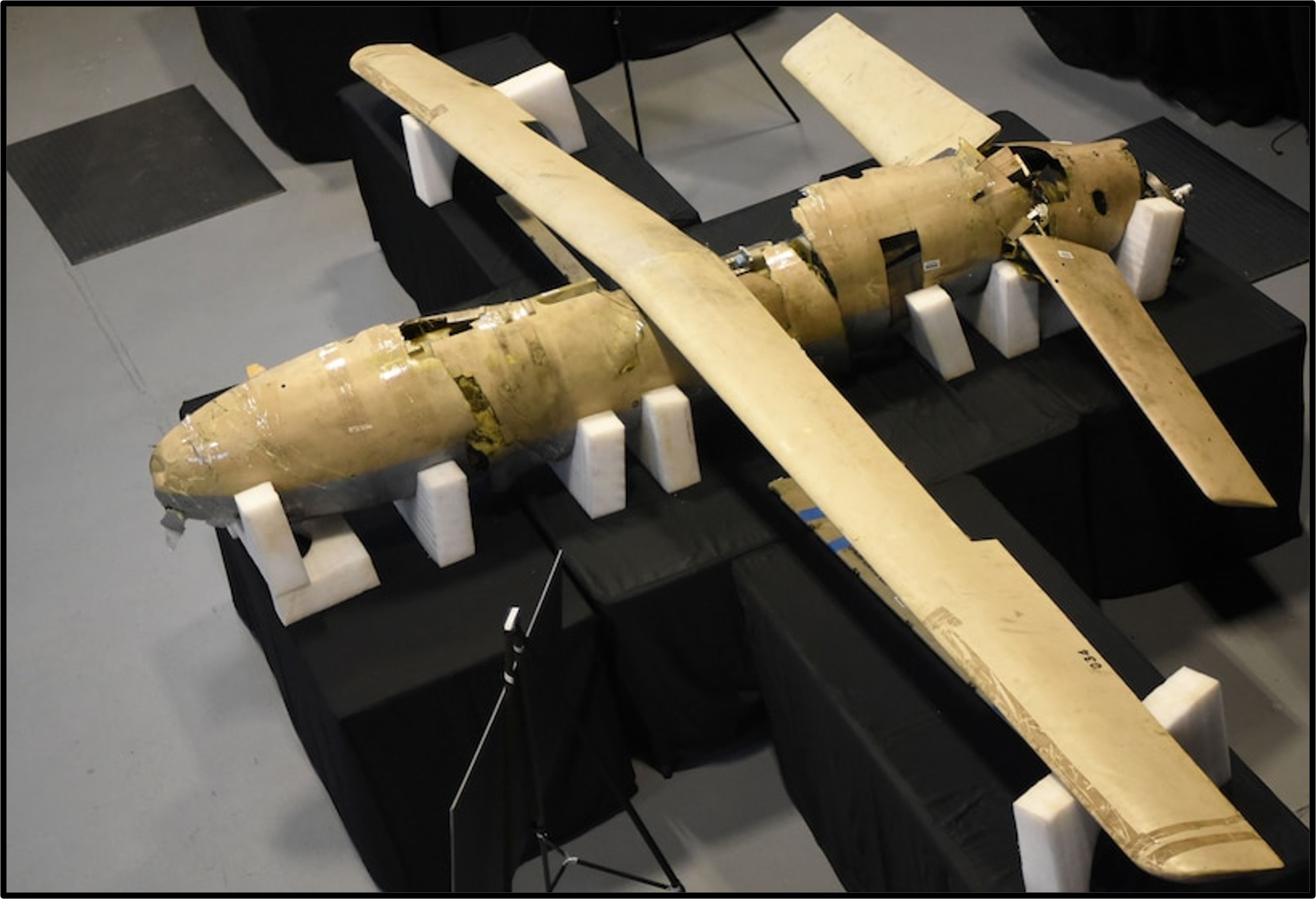

The Iranians are pragmatic. If they get the opportunity to look at how somebody else is doing something and think it’s a good idea, the Iranians will copy it. Tehran has managed to knock a few American drones out of the sky. At one point, they appeared to copy the U.S. ScanEagle, which is a small UAV. Given its inability to buy components in the open market, Iran’s approach has to be based on domestic technology.

The extent to which Iran could successfully reverse engineer has got to be treated with some caution, particularly the RQ-170, a U.S. drone shot down by Iran in December 2011. The Iranians claim that they are now manufacturing an equivalent. One has to take that with a very substantial pinch of salt. It's one thing to make a model of a similar shape. It's another thing completely to have replicated that capability in its totality, which is doubtful. Some claims are made for internal propaganda purposes. That's not to say Iran doesn’t have a capable UAV inventory. But it is nowhere near on par with the United States, China or Israel.

Do other states in the Gulf have drone fleets?

The regional powers have looked at the development of UAV technology and its adoption by the first and second tier armed forces of the world and decided that they need these capabilities as well. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) all have bought UAVs. Often the first port of call was the United States. But the United States had a fairly restrictive approach in terms of sale to the region until very recently. The United States has sold advanced drones to the UAE, and it sold some smaller systems throughout the region.

The next port of call for most of these Arab nations was China, particularly when the interest was in an armed system. China has taken a much more transactional approach. U.S. reluctance provided a market opportunity for China that it was quick to take advantage. There are armed Chinese systems in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Egypt. Countries like Saudi Arabia and the UAE are keen to develop their own industrial base and to produce domestic UAVs in parallel to acquiring off the shelf.

How do Iran’s drones compare with others in the region?

There is quite a gulf in terms of technology. Western equivalents are going to be considerably more capable than what Iran produces. Iran’s medium-to-large UAVs can probably stay in the air for up to 20 hours while carrying fairly sophisticated sensors, payloads and a range of weapons. That's the other element that we've seen Iran develop—small weapons suitable for UAV carrying and use.

While Iran’s drones don't stack up in terms of technology, their capabilities can’t be dismissed. These systems are designed around what Tehran needs. Iran doesn’t necessarily want an extremely capable system which may demand highly capable operators, which it may yet not have. And the UAVs and direct attack munitions have to be cost effective.

Has Iran exported its drones to regional allies or proxies?

Yes. Drone exports help build relationships with regional actors. Iran has supplied drones to Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen. Tehran puts these capabilities in the hands of its network of regional actors so it can influence their behavior. Iran can also make considerable mischief for some of its regional rivals. The Houthis have claimed a variety of attacks using UAVs, ballistic systems and cruise missiles. An awful lot of that technology doesn't actually originate from inside Yemen. These systems strongly resemble Iranian systems. Exporting systems also allows Iran to see how their systems behave in a combat environment. It's a battle lab: Have I designed this properly? Does it work the way I want it to? Does it provide the information that I want to get to my ground forces? Does it let me attack the targets that I want to attack with these weapons? Are the weapons effective?

Does Iran’s drone fleet pose a threat to U.S. military or its presence in the Middle East or South Asia?

UAVs are something the U.S. military undoubtedly factors in. The United States would be foolish to ignore it. UAVs are part and parcel of what the U.S. thinks about when it looks at Iran's military capability: How do we deal with this? How do we manage it?

Does Iran’s drone fleet change the military balance or the balance of intelligence capabilities in the region?

In terms of the overall military balance, I don't think it does. Why did the Iranians go down the UAV path? It was initially to offset what they saw as a conventional weakness or conventional limitations, at least in terms of its combat air inventory.

The Iranians manned combat air inventory is based around what the shah acquired from the U.S. in the 1960s and 1970s, along with a small number of Soviet and Chinese aircraft. It's an aging fleet. The Phantom fleet, the F-14 fleet, these are all old aircraft now. The fact that the Iranians have managed to keep some of those types airborne for as long as they have speaks to their competency in defense aerospace engineering. To still have these in operational numbers is an achievement in itself. That aerospace engineering capability spilled over into the UAV field.

The Iranian UAVs that provide intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance are adequate in a low-to-no threat environment. But as soon as its drones come up against an opponent with a capable air-to-air and surface-to-air missile engagement capacity, Tehran has a problem. Iran can start to lose UAVs very quickly. None of their drones are stealthy. Most of them are pretty slow. Against a capable opponent, their ISR and attack capabilities are going to be limited. But the drones’ limited capabilities doesn’t mean you can discount them.

How do drones fit into Iran’s wider military strategy in the Middle East?

UAVs are partially to offset perceived weaknesses or other limitations in their military. Iran’s conventional air power is based on aging systems. UAVs offset that to an extent. UAVs are not a replacement for crewed aircraft, but they give Iran some capability. In terms of wider regional influence, UAVs allow Iran to provide capabilities to regional proxies and to complicate the threat picture for regional opponents.

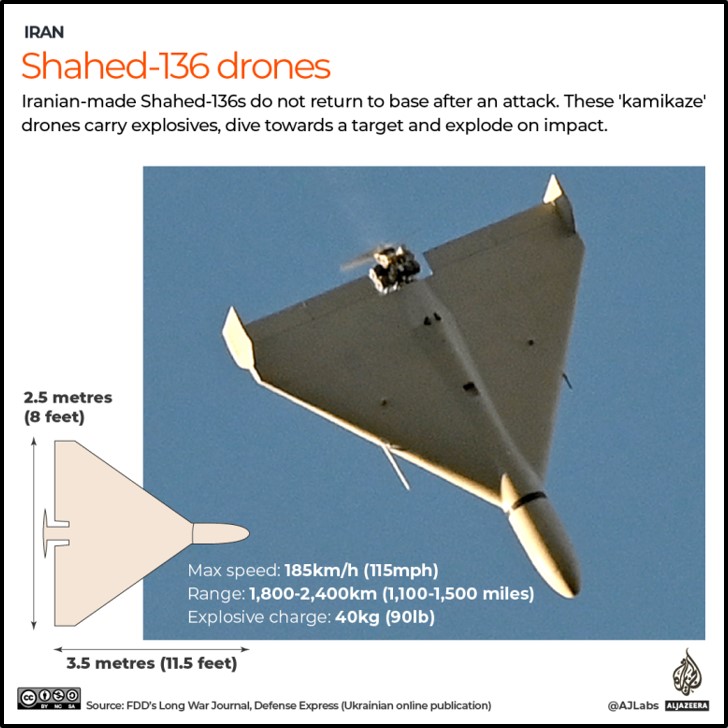

In 2022, Russia looked to Iran to provide UAVs and direct attack munitions, commonly known as suicide drones, including the Shahed-131 and Shahed-136, to use against Ukraine. The relationship that has emerged opened the scope for wider defense cooperation. The flow of military technology between Iran and Russia was not surprising. But Russia seeking Iranian defense equipment for its arsenal was less predictable. In return, Iran may receive modern combat aircraft. In 2023, the Islamic Republic expected to receive Sukhoi Su-35 multi-role fighters from Russia, which reflected the growing defense relationship.

Douglas Barrie is senior fellow for military aerospace with the International Institute for Strategic Studies. He previously worked as the London bureau chief for Aviation Week and Space Technology, European editor of Defense News, defense aviation editor for Flight International and deputy news editor for Jane’s Defense Weekly.