Hadi Semati is a former professor in the faculty of Law and Political Science at Tehran University and a former scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He is now an independent analyst.

What are the stakes in the 2021 presidential election?

The question of who will succeed Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei looms large over the election. Khamenei turns 82 this year and has not shown any obvious signs that he is in poor health. But Iran’s political factions are positioning themselves in anticipation of the succession, which may not come for years. But should he die or become too sick to fulfil his duties in the next four years, the next president could influence the succession.

The succession issue is not the only driver in the election, but it is tied to a wider generational shift in Iranian society and politics. Khamenei’s generation – the old guard that led the 1979 revolution and guided the country through the 1980-1988 war with Iraq – is gradually retiring or passing away. Meanwhile, the next generation – including men and women who were children during the revolution – is looking to take up important posts in the judiciary and executive branches.

Two candidates running in the 2021 election are from the new guard: Alireza Zakani, who was born in 1965, and Amir Hossein Ghazizadeh Hashemi, who was born in 1971. Both are conservative members of Parliament. Their qualification by the Guardian Council, which vets all candidates, indicates that their generation is finding a way into the political process at increasingly higher levels.

Many conservatives in their generation fought in the war with Iraq, then went to college in the 1990s. But they did not find government jobs during the presidency of Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005), a reformist. They mostly entered government service during the presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005-2013), a hardliner. They were left out of the system during the presidency of Hassan Rouhani (2013-2021), a centrist. Now that Rouhani is on his way out, these conservatives have an opportunity to return to power.

What will be the decisive issues in the campaign?

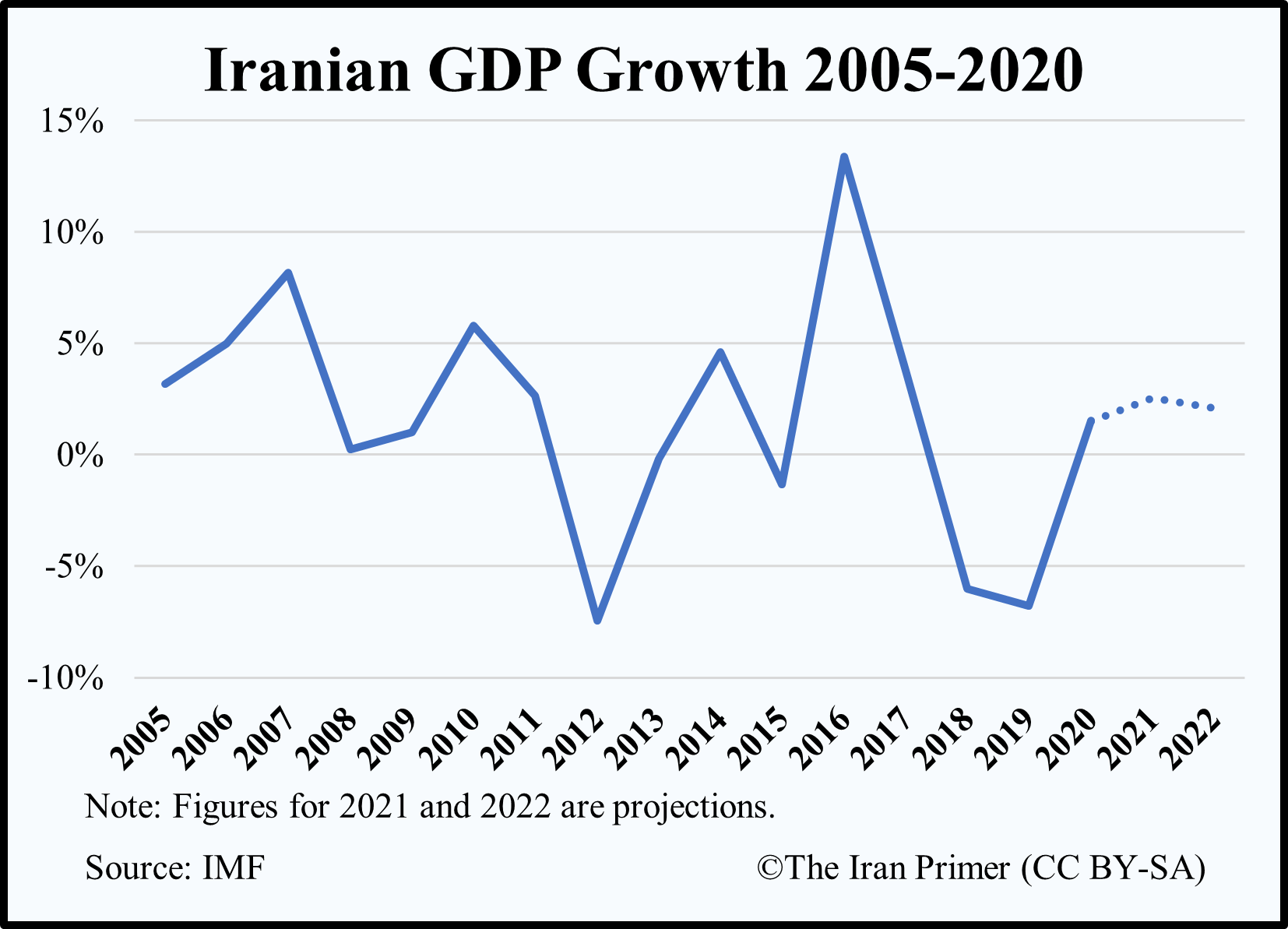

The economy is the main issue for voters. Iranians are dealing with inflation, poverty, unemployment and skyrocketing prices for basic household goods. Conservatives have done a good job at playing the blame game. They have pegged Iran’s economic problems on the Rouhani administration, especially since the United States withdrew from the nuclear deal and reimposed sanctions in 2018. They have accused Rouhani of looking to the West to solve Iran’s economic problems.

The economy works in favor of the conservatives, who have also built a reputation for tackling corruption, an important issue among voters. Corruption is so systemic that many voters are fed up with the system as well as with the political elites. People have lost their trust in how the state distributes wealth and manages market forces. Ebrahim Raisi, one of the seven approved candidates and the current judiciary chief, has made corruption his signature issue. The judiciary, dominated by hardliners, has prosecuted several high-profile cases. In 2019, Hossein Fereidoun, the brother of President Rouhani, was sentenced to five years in prison for corruption and bribery. In 2021, Mahdi Jahangiri, the brother of Vice President Eshaq Jahangiri, was sentenced to two years in prison for corruption. Such sentences have politicized the debate on corruption and tarnished the reputation of Rouhani’s centrist camp more broadly.

On the other hand, Rouhani and his team have failed to sell the public on their economic policies. They managed to keep Iran’s economy afloat despite major obstacles, including U.S. sanctions, the oil revenues frozen abroad, and the COVID-19 pandemic. People did not feel that Rouhani’s efforts improved their situation. The public has largely given up on the economic benefits that he promised when the nuclear deal was brokered in 2015. Even with new diplomacy on the nuclear deal, voters have concluded that future benefits will be limited if the United States lifts some sanctions. A sense of hopelessness about the economy has set in, largely due to the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign, but also due to the Biden administration’s approach to reviving the JCPOA.

Social and cultural issues are marginal to the election because none of the candidates are likely to make drastic changes in that field. Even conservatives seem to have realized that there are limits to restrictions that they can impose. The mandatory hejab (head covering) is an illustrative example. Many women routinely wear a small scarf on top of their head and let most of their hair show.

What are the big decisions the next president has to make?

The first major decision will be how to proceed on the nuclear diplomacy. The result of negotiations with the United States and five other world powers will directly impact the next president’s economic agenda. To revamp its economy, Iran needs sanctions relief for its banking and oil sectors.

The second decision will be over how to deal with poverty and massive inequality. Iran does not have a much of a tax base, so the next president will be challenged to provide for the population with limited revenues, especially if all sanctions are not lifted.

The second decision will be over how to deal with poverty and massive inequality. Iran does not have a much of a tax base, so the next president will be challenged to provide for the population with limited revenues, especially if all sanctions are not lifted.

The third decision will be over staffing. There could be significant personnel changes across many ministries if a conservative, such as Raisi, is elected. When Ahmadinejad took office in 2005, he hollowed out the bureaucracy of experienced technocrats, and the results were detrimental. Raisi could face pressure from hardliners to make a fundamental change in the bureaucracy. This is, in part, also tied to the generational shift. The new guard is eager to push out the old guard.

The next president could have a lasting impact on how the country is run by staffing ministries with more youth. On May 11, Khamenei said that an administration that harnesses experienced statesmen and youth could quickly solve the country’s problems. “The administration is a large organization where hundreds of efficient and determining managers work, all of whom can host – so to speak – pious, intellectual and revolutionary youth, and these youth should be able to participate in decision-building, decision-making and executive areas,” he told students. “Transformation is necessary.”

Many up-and-coming conservative youths, now in their 20s and early 30s, are more hardline than previous generations. They tend to be more ideological and consumed by questions of social justice and corruption. They lack maturity because they did not go through the “school” of the 1979 revolution, nor did they experience the eight-year war with Iraq. They have grown up as insiders. They have also been socialized to believe in a simplistic dichotomy, in which conservatives are the good guys and reformists are the bad guys. They think reformists are influenced by the United States and Western culture.

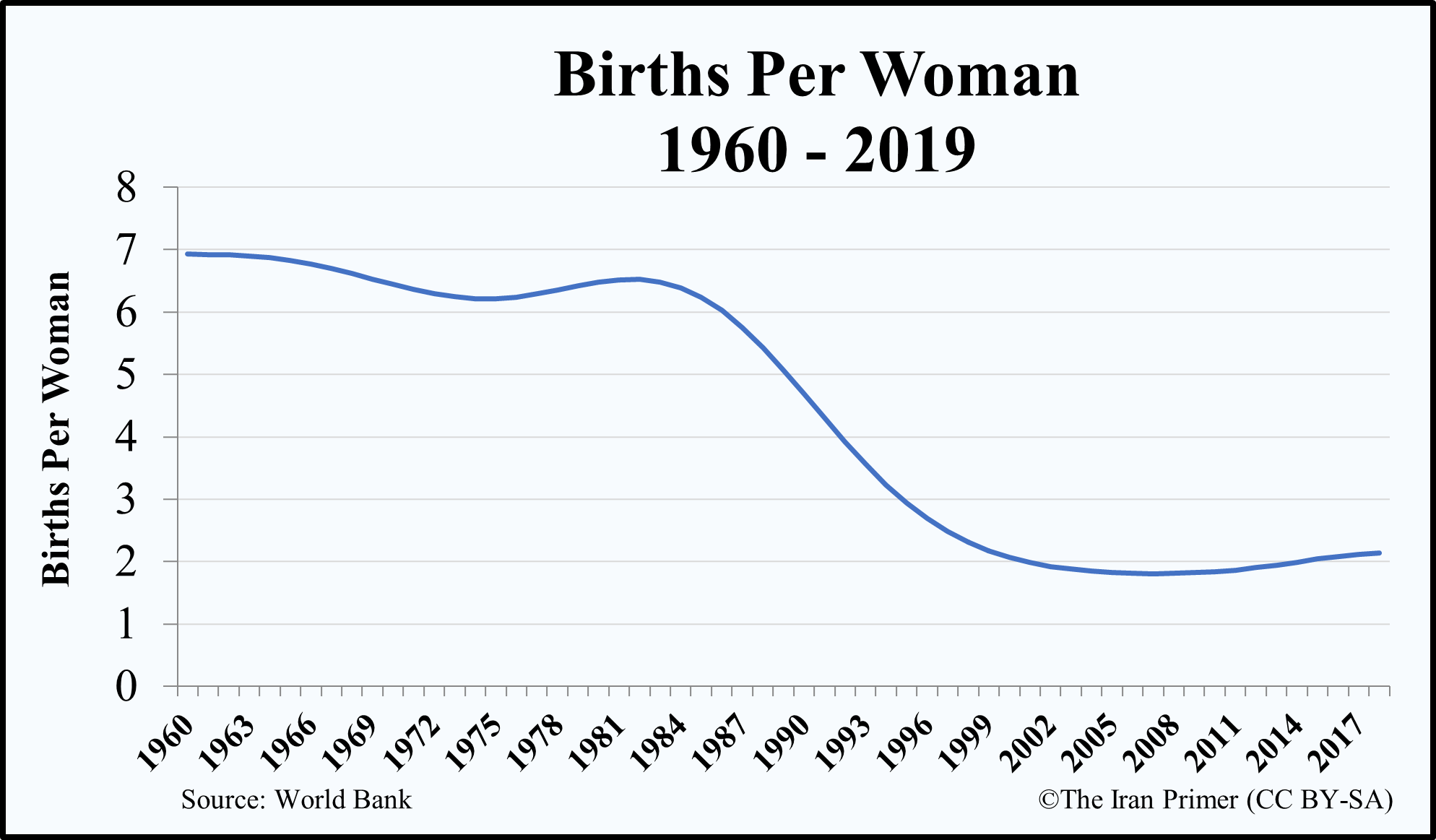

A fourth issue that the next president will face is Iran’s shrinking population. In the first decade after the 1979 revolution, Iran’s population almost doubled from 34 to 62 million. The leadership realized that it could not afford to feed, cloth, house, educate and employ such a fast-growing population. So, starting in 1989, it implemented a family planning program that eventually brought the fertility rate down from 5.4 births per woman in 1988 to about 2.1 births, replacement level, in 2000. The rate has hovered around two births since then.

A fourth issue that the next president will face is Iran’s shrinking population. In the first decade after the 1979 revolution, Iran’s population almost doubled from 34 to 62 million. The leadership realized that it could not afford to feed, cloth, house, educate and employ such a fast-growing population. So, starting in 1989, it implemented a family planning program that eventually brought the fertility rate down from 5.4 births per woman in 1988 to about 2.1 births, replacement level, in 2000. The rate has hovered around two births since then.

Within the next decade, Iran will have a large elderly population without a sizeable young labor force to support it. Many young people, especially those with higher education, are searching for work opportunities abroad. The welfare state, with limited revenue, must find a way to provide for an elderly population and a younger population faced with little opportunities for employment at home.

A fifth issue that the next president will need to deal with is the depoliticization of society. Politicized citizens make calculations and organize themselves into factions to pursue their interests. But a depoliticized population can be a liability for the system because mobs are more likely to form when things go wrong. In 2019, protests erupted over economic grievances. The spark was an overnight announcement of a gas price hike. Angry demonstrators burned banks, government buildings and gas stations. Security forces reportedly killed hundreds of demonstrators and detained thousands.

What does the final list of candidates tell you about what the system is willing to tolerate in terms of diversity?

The Guardian Council’s elimination of Ali Larijani, who was speaker of Parliament for 12 years from 2008 to 2020, and Eshaq Jahangiri, a vice president since 2013, shows that the system’s threshold for tolerance is getting lower and lower. Five of the seven approved candidates are conservatives, and the other two candidates do not have name recognition at the national level. The field is so narrow that voters are faced with an imposed choice.

The disqualification of the most prominent reformists and centrist candidates was a power play. The system has not been able to eliminate the reformist camp, or at least the electorate’s desire for incremental reforms, through the ballot box. Reformists would almost certainly win an election if the turnout was high. So the Guardian Council took the serious contenders out of the running. The system does not want to take a risk on a surprise result, especially in the next four years, when there might be a transfer of power to Khamenei’s successor.

The system is willing to accept a deficit in legitimacy to guarantee its preferred result, which appears to be a victory for Raisi. He cannot afford a second electoral loss if he is to succeed Khamenei. But the system has not necessarily decided on the succession. There will be a lot of jockeying and power plays when the time comes. In 2017, Rouhani won with 57 percent of the vote, with Raisi coming in second with 38.5 percent, in a four-way contest. But the judiciary chief could face a conundrum. If he wins the 2021 election, but the turnout is low, his image could be damaged. If the election goes to a runoff (because he doesn’t get more than 50 percent in a seven-way contest), he could also appear to be a weaker president without a significant public mandate.

Some conservatives were not happy with the candidate list because they wanted to show that they can win a roughly competitive race. But conservatives will try to explain the low turnout by citing limitations imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. They may also blame Rouhani’s poor economic performance for making people disinterested in politics.

It is not clear how the Guardian Council’s decision was made, or if Khamenei was even aware of it at first. The system may have picked its favored candidate or candidates before the final list was announced. In the week before the final list was announced, the spokesman for the Guardian Council said that low turnout would not be a sign of a lack of legitimacy. In the days before the final list was announced, Hossein Dehghan, a former defense minister, and Rostam Qasemi, a former oil minister, dropped out of the race. They may have been given a signal to step aside before getting disqualified.

The list of approved candidates suggests that Iran is moving towards a single-party system dominated by conservatives. Until now, the Islamic Republic has had vibrant elections despite limitations on full participation because of the Guardian Council’s vetting of candidates. But the undemocratic elements of the system are gaining power. The reformists--the loyal opposition within the revolutionary camp--has been pushed out. The dominant trend, which has many factions, will debate policy and how to best preserve the Islamic Revolution, but the divisions will not be sharp.

What is the interest level among Iranians in voting this time?

This is the first election in which people from across the political spectrum are discussing the likelihood of a low turnout, perhaps the lowest since the 1979 revolution. Polls have suggested that turnout could be as low as 30 percent. Political nihilism or exhaustion is widespread. But the added dissatisfaction with the list of approved candidates could keep even more people away from the polls. For the first time, the government does not seem to care about public legitimacy.

#Ahmadinejad today revealed that he cast a protest vote in 2013 and 2017 elections, but this time around he will boycott the vote if the Guardian Council doesn’t qualify him. Everybody thinks the ball now is in the Guardian Council’s court. 4 pic.twitter.com/gosLiPt70S

— Fereshteh Sadeghi فرشته صادقی (@fresh_sadegh) May 12, 2021

The middle-class constituency for reformist candidates will probably not turn out this time. On May 26, the Reformist Front said that it would not endorse a candidate, although it stopped short of calling for a boycott of the election.

On May 26, Ahmadinejad said that he would boycott the election in response to the Guardian Council’s decision to bar him from running twice in a row. Some of his supporters may follow his example.

But Iranian voters can change their minds at the last minute and decide to vote. Turnout may be lower in major cities – especially Isfahan, Mashhad, Shiraz, Tabriz, and Tehran – that have large middle-class populations. But turnout in small towns and rural areas may be higher, especially because the presidential election will coincide with municipal elections.

How will the pandemic influence interest in going to a public poll?

Fears of COVID-19 transmission could also contribute to a low turnout. Less than six percent of Iran’s population is vaccinated. But the Interior Ministry has discussed opening more outdoor polling sites. It also decided to extend voting hours until 2:00 a.m. on June 19, which could help limit the size of crowds.