Iran’s car industry has been under growing pressure since the Trump Administration re-imposed sanctions in August 2018. The challenges are economic, demographic, environmental, and medical—a microcosm of changes in the Islamic Republic since the 1979 revolution. Iran has gone through waves of sanctions over the past four decades that have spilled over into daily life, including access to transportation as the population mushroomed to 82 million.

To meet the demand, automotive production rose by more than 18 percent in 2017. Iran produced 1.4 million cars and commercial vehicles, ranking sixteenth in the world. (Its population size ranked seventeenth.) But by June 2018, a month after sanctions were renewed, car production dropped by 29 percent compared with the same month a year earlier due to the currency crisis and other byproducts of sanctions. Foreign companies that made cars in Iran — including Peugeot and Renault — decided to leave because U.S. sanctions were also imposed on any company that did business with Tehran. Renewed sanctions led to delays in car deliveries and a shortage of parts.

Auto History

Car imports fell by nearly 50 percent after the revolution and the subsequent nationalization of the automotive industry. The theocracy’s new policy was predicated on limiting foreign influence by curbing imports and economic dependence on the West. In the 1980s, the grueling eight-year war with Iraq diverted industrial production and human resources. Production of passenger vehicles fell from 120,000 a year in 1979 to a mere 5,000 in 1989. The combination of self-imposed import bans and low production during the war led to high demand for cars with very little supply.

During reconstruction after the eight-year war, the automotive industry was pivotal in addressing unemployment and other economic challenges. Manufacturing quotas and industry protections helped rebuild the car industry in the early 1990s by encouraging local production of parts and prohibiting the import of totally assembled cars. Domestic growth in production proved to be an arduous process slowed by infantile technology and limited manufacturing capabilities. In response, Iran’s two largest manufacturers, Iran-Khodro and SAIPA, established relations with multinational firms Kia and Peugeot. The agreements allowed Iranian firms to rapidly increase their technological capabilities through reverse engineering and technology licensing. Meanwhile, Kia and Peugeot were able to locally assemble low-end cars, such as the Kia Pride and Peugeot 405, to meet a growing consumer market.

From 2000 to 2010, car production increased almost six-fold, according to The Washington Post. The two largest local manufacturers, Iran-Khodro and SAIPA, employed more than 100,000. (The last Paykan was produced in 2005.) By 2012, Iran was the top car producer in the Middle East. In 2013, its car industry employed at least 700,000, roughly four percent of the work force. It exported some 50,000 cars to countries such as Iraq and Syria but also as far afield as Venezuela and Russia. In 2016, the industry accounted for about 10 percent of GDP, making it the second largest industry in Iran after oil and gas, according to a UNESCO report.

U.S. Sanctions

Economic sanctions on Iran have been a recurring feature of U.S. policy over the last four decades. Washington imposed an import ban on oil after the 1979 takeover of the U.S. embassy in Tehran. Sanctions were lifted after the 52 hostages were freed under the terms of the 1981 Algiers Declaration. Three years later, President Ronald Reagan designated Iran a state sponsor of terrorism, a move triggering multiple sanctions that remain in place today, such as restrictions on U.S. foreign assistance, prohibiting U.S. arms sales to Iran, and opposing multilateral lending from institutions such as the World Bank. Reagan era sanctions were too limited in scope and unilateral in nature to impact Iran’s auto industry. Even President Clinton’s expanded sanctions in 1995, which banned all U.S. trade and investment with Iran, had negligible impact on Iran’s growing car industry. Between 2006 and 2011, the United States, European Union, and the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) coordinated six rounds of sanctions in response to Iran’s controversial nuclear program. These sanctions were limited in scope and targeted only Iran’s nuclear and ballistic missile programs. They did, however, provide international legal justification for more expansive sanctions by the United States and the European Union.

The Trump Administration’s sanctions, in August 2018, reimposed many penalties and restrictions lifted in connection to the JCPOA, including ones targeting Iran’s cars. “The U.S. prioritizes the auto industry over the energy sector in its sanctions regime,” Morteza Mortazavi, head of an Iranian auto suppliers union, told Al-Monitor in August 2018. “That means they are conscious about the significant number of jobs the industry has created for us.”

After President Trump withdrew from the JCPOA in 2018, Iran’s currency—the rial—lost two-thirds of its value against the dollar. Cars grew more expensive and foreign-produced parts harder to find as Western manufacturers—including Peugeot, Renault, and Daimler—pulled out. A major decrease in car production, after the U.S. renewed sanctions, was expected to have a rippling impact. Up to 450,000 jobs in the auto parts industry were at risk. The loss of job opportunities could have the deepest impact on the young, who were already facing high unemployment. In 2017, youth unemployment was 29.9 percent, according to the World Bank.

Social and Medical Repercussions

The public’s decreasing access to cars has intersected with a baby boom produced during the first decade of the revolution, when the population almost doubled. By 2017, the post-revolution generation — by then in young adulthood and hungry for transportation — accounted for over half the population as well as the majority of voters. Almost 75 percent of the population was also urbanized, increasing the need for cars since public transportation was limited or unavailable.

The Iranian hunger for cars has created other problems, including dangerous levels of pollution. Tehran had 4.24 million vehicles in 2014, according to government statistics. By 2018, the number of cars in Tehran soared to five times its infrastructure capacity, according to Tehran Police Chief Hassan Rahimi. There were then more than 17 million vehicular trips per day in Tehran. Many of the vehicles had outdated technology, the World Bank reported. Heavy-duty vehicles, like buses and large trucks, made up just 2 percent of vehicles but were by far the heaviest polluters. These vehicles contributed nearly 85 percent of particulate-matter pollution, or microscopic particles that can affect the heart and lungs once inhaled.

For years, high fuel consumption and poor emissions control have plagued Iran’s densely populated urban centers. More than 4,000 people die in Tehran annually from pollution, according to a 2018 World Bank report. (The report used the Global Burden of Disease methodology and Integrated Exposure-Response functions outlined by a 2016 World Bank-Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation publication.) Tehran has sporadically been forced to shut down public schools and warn against allowing the elderly or babies to go outdoors due to smog.

Aged technology continues to complicate Iran’s transportation woes. Nearly 40 percent of Tehran’s municipal buses were between 10 and 20 years old, while nearly 25 percent of trucks in the city were more than 20 years old, according to a 2016 study. Diesel vehicles lacked technologies—such as diesel particle filters, selective catalytic reduction, and diesel oxidation catalyst—to treat exhaust. Cars and motorcycles often relied on carburetor engines, as opposed to fuel injection, which were typically less efficient and produced higher emissions. “While only 9 percent of passenger cars [in Tehran] are carburetor-equipped, they contributed to 51 percent of total emissions from passenger cars,” the World Bank reported in April 2018.

Attempts to curb urban pollution have centered on natural gas vehicles. The government mandated diesel particle filters on all new heavy-duty vehicles manufactured after September 2016. In 2018, there were more than 4.5 million vehicles using natural gas in Iran, the second highest number in the world, according to official statistics. In 2018, Tehran began working with Japan to address poor city planning. The proposed Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) program sought to introduce more efficient city planning and better public transportation to alleviate urban congestion and high pollution. (An initial data collection survey was finalized in September 2018.)

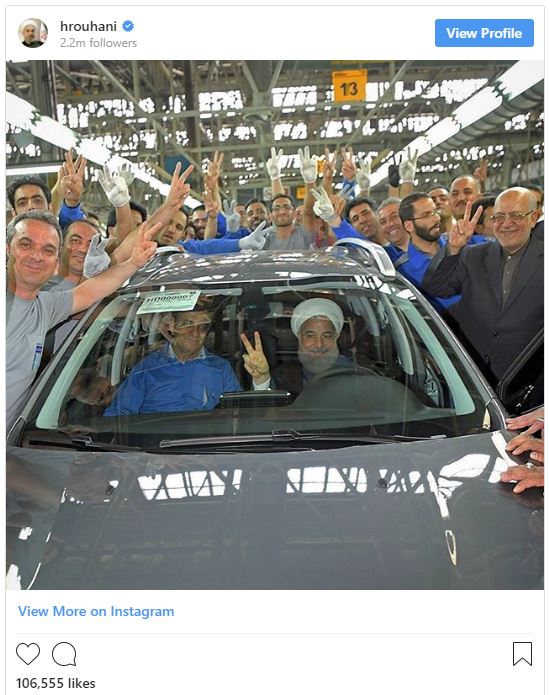

Cars in Politics

Cars have been potent symbols in Iranian politics, often used as tools to cultivate a public image. During the 1997 presidential campaign, candidate Ali Akbar Nateq-Nouri was chauffeured around in a Mercedes, while his opponent, Mohammad Khatami used a weathered bus or a domestically-produced Paykan on the campaign trail. Khatami won the election in an upset, with voters at the polls frequently citing his personal character and integrity, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad pointedly drove his 1977 white Peugeot — with no chauffeur — when he was mayor of Tehran between 2003 and 2005. He continued to cultivate the image of a humble man of the people in his successful bid for the presidency in 2005.

During the June 2013 presidential campaign, the cars of two contenders were again a hot topic. Ayatollah Hashemi Rafsanjani’s political rivals noted that he was chauffeured around in a dark blue Mercedes as evidence of his wealth and alleged corruption. In contrast, Said Jalili drove a beat-up Kia Pride, an inexpensive Korean car assembled locally and driven by many Iranians. Neither won.

The United States has even exploited the types of cars driven in Iran to address injustices. In September 2018, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo accused Iran’s leaders of corruption and cited their vehicles of choice to illustrate his point. “The president of Iran, Hassan Rouhani himself, has said many people have lost their faith in the future of the Islamic Republic and are in doubt about its power,” Pompeo said at a United Against Nuclear Iran event in New York. “This attitude, of course, is understandable with one-third of Iranian youth unemployed, while government parking garages are filled with Range Rovers and BMWs.”