Katayoun Kishi

More than 12,000 Iranians registered to run in the February 26 parliament election. Women, in particular, signed up in large numbers—a total of 1,434. Both set a new record. The diversity suggests the possibility of significant change in the next Majles. In the past, however, the powerful Guardian Council has disqualified many candidates. Those who registered will be vetted before the elections. The following is a primer on historical trends in parliamentary elections.

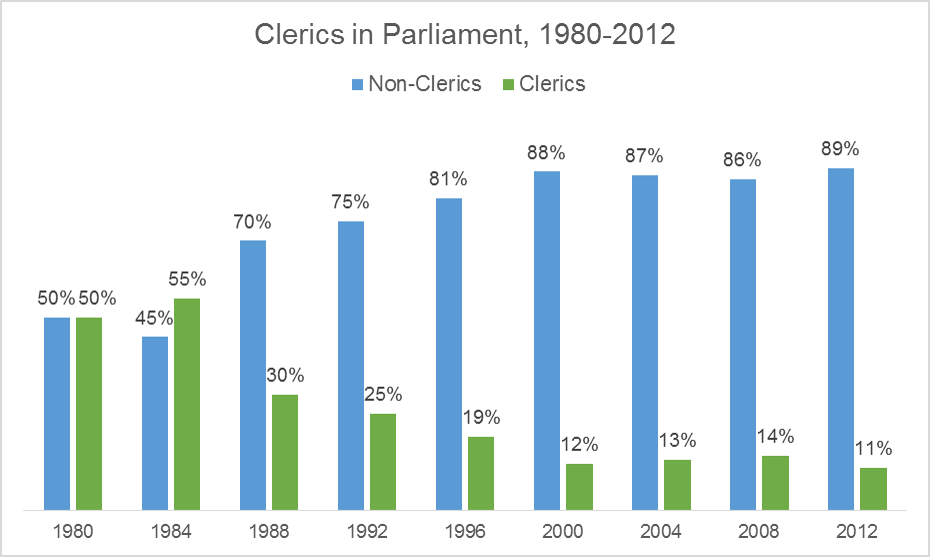

Clerics

Since the first parliament in 1980, the proportion of clerics in the legislative body has steadily decreased, from half of lawmakers in 1980, to 11 percent in 2012. About 30 members of the current 290-member parliament are clerics.

Despite their diminishing influence in parliament, clerics still have a firm grip on most of Iran’s political institutions. One of the most powerful bodies is the Guardian Council, which is in charge of vetting candidates and approving laws passed by parliament. It has 12 members, half clerics and half jurists. The Assembly of Experts is another clerical body that monitors the supreme leader’s power, although it has never seriously questioned his actions. It does, however, select the supreme leader, usually from within its own ranks. A third group is the Expediency Council, an advisory body to the supreme leader, which has always been chaired by a cleric.

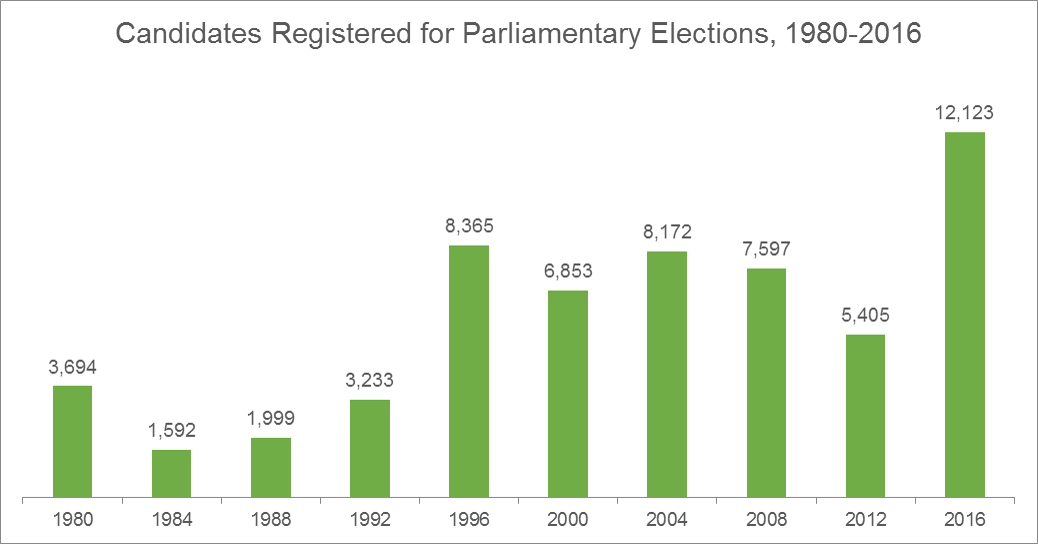

Candidates

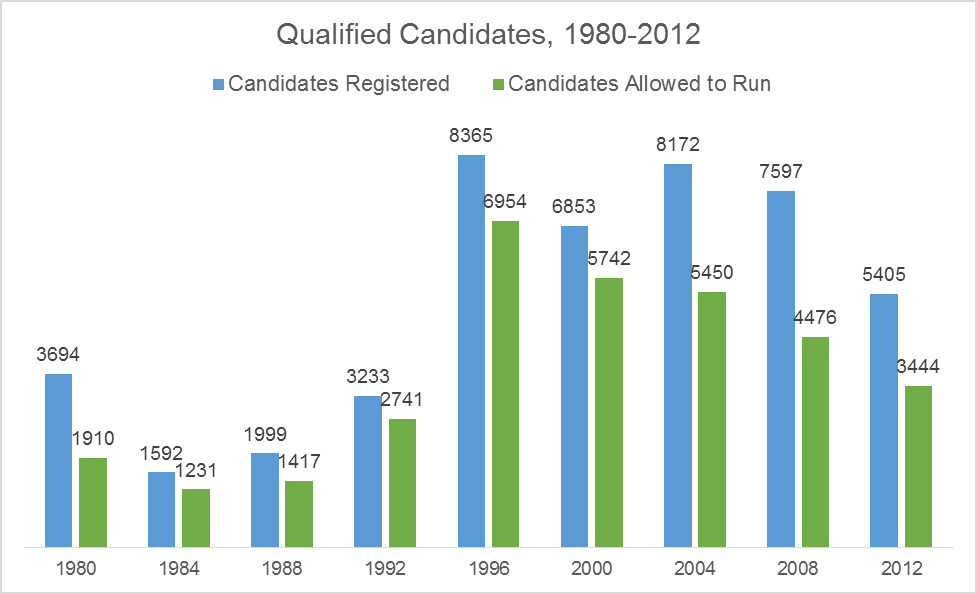

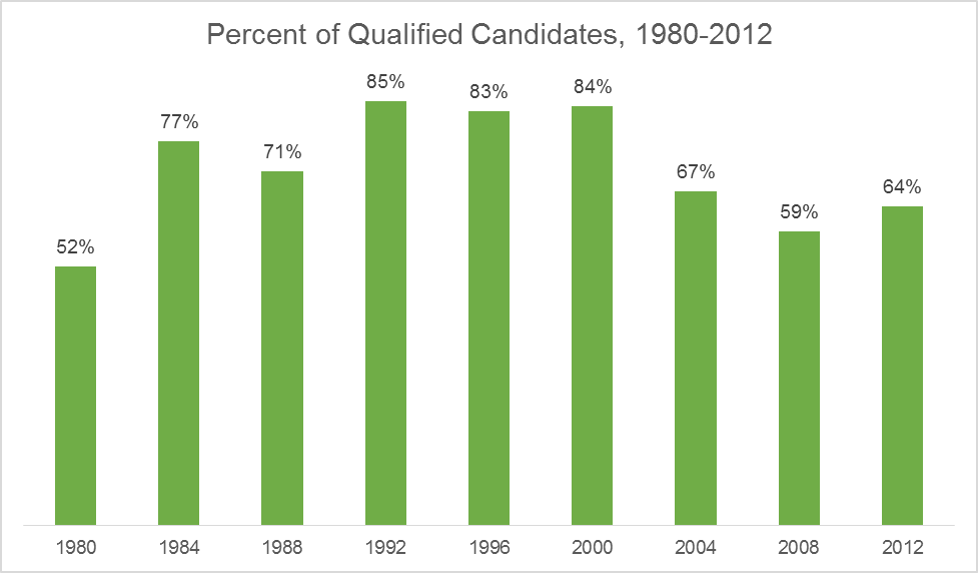

The number of candidates expected to register far exceeded expectations. In August 2015, Interior Minister Abdolreza Rahmani Fazli predicted that 4,000 people would register for the parliamentary and Assembly of Experts elections. In December, Fazli announced that 12,123 candidates registered to run just for parliament—more than double the 5,405 who registered in 2012. In the Tehran province alone, 2,477 candidates have signed up to compete for 35 seats. (Another 801 registered to contest the Assembly of Experts, a 62 percent increase in candidates.)

In past elections, the Guardian Council tended to approve conservative or hardline candidates and disqualify many reformist candidates, insisting that all decisions were based on the law. It disqualified almost 2,000 candidates for the 2012 parliamentary election – about 34 percent of those who registered. In December, Mohammad Reza Aref, a former vice president in the Khatami administration, appealed to reformers to run. Some reformist groups have sought to form coalitions with moderates and centrists to get past the Guardian Council. “We are ready to cooperate with moderate and wise conservatives and form a joint front against those who are after sectarian rather than national interests,” Hossein Naghashi, a member of the reformist Islamic Iranian National Alliance party, told The Guardian. Hardliners have criticized the strategy. The Council will publish its final list of qualified candidates in early February.

Women

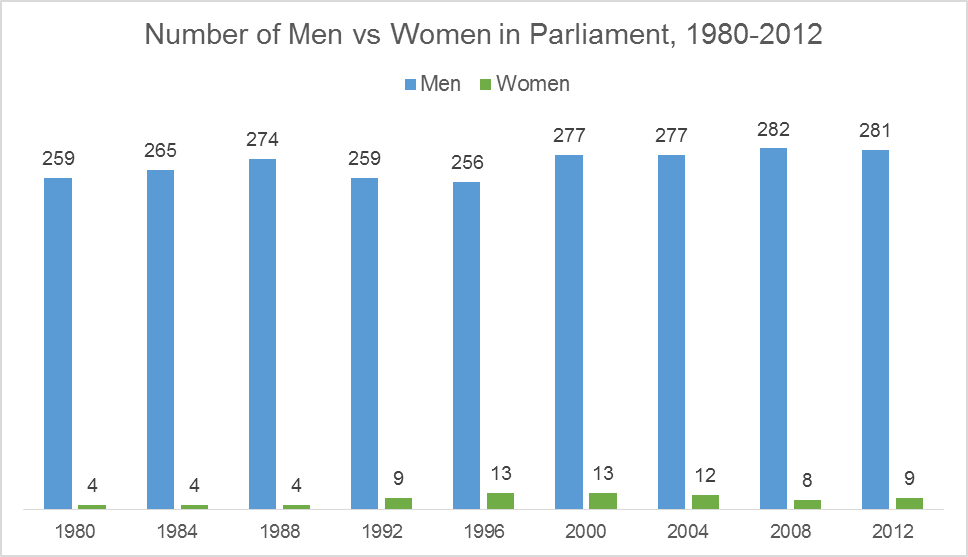

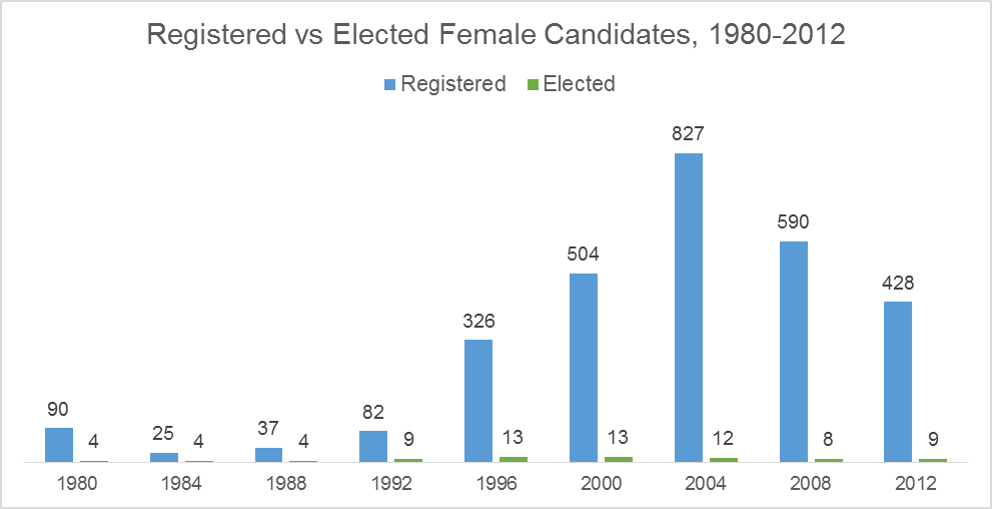

Women have constituted a small minority of parliament members since the first Majles. Their numbers peaked at 13 members in the 5th Majles (1996-2000) and 6th Majles (2000-2004), but have been declining ever since. They comprised only three percent of the 9th Majles (2012-2016), with nine female members in the 290-member body.

For the 2016 election, women account for 12 percent of registered candidates. The number more than tripled from the 2012 poll, when 428 women registered. Fatemeh Hashemi, member of the 5th Majles and the daughter of former President Rafsanjani, is one of the women registered to run in the 2016 election.

Centrists and reformers fielded more female candidates to draw a wider constituency, Aref told reporters in December. Speaker Ali Larijani told the women’s caucus in parliament that he hoped for more female representatives, at least one from each of Iran’s 31 provinces. President Rouhani also encouraged women to register for parliament seats.

Religious Minorities

Iran’s constitution mandates five reserved seats in parliament for religious minorities. Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians are guaranteed seats as follows:

- Two seats for Armenian Christians

- One for Assyrian and Chaldean Christians

- One for Jews

- One for Zoroastrians

Some religious minorities, however, are excluded. The Baha’i faith, which is reportedly Iran’s largest religious minority, with up to 350,000 members, is deliberately excluded because it is not officially recognized. Religious minority candidates, like all candidates, must pass the Guardian Council. But representation in parliament does not necessarily translate into equal rights for members of non-Muslim faiths. Many minorities still face discrimination in work, education, and property ownership.

Under Article 28 of the Elections Act of Islamic Consultative Assembly, all parliamentary candidates must meet the following qualifications:

- Believing and practically binding to the Islamic Republic of Iran

- Iranian Nationality

- Binding to the Constitution

- Holding at least a Master’s Degree or its equivalent (excluding incumbents)

- Having no bad reputation in the elections station

- Physical Health at the extent of being able to see, hear and speak

- At least aged 30 and at most aged 75

Some data is based on previous articles by Yasim Alem on The Iran Primer.

Katayoun Kishi is a research assistant at the U.S. Institute of Peace.