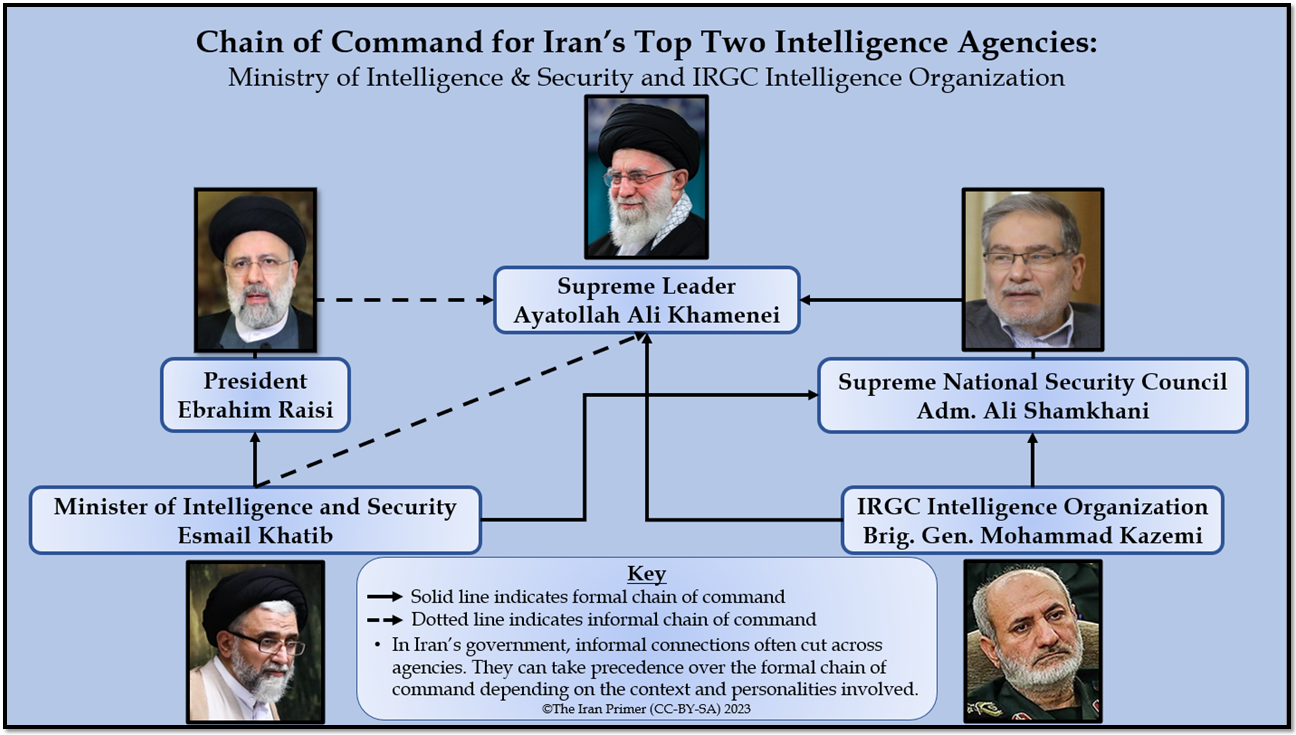

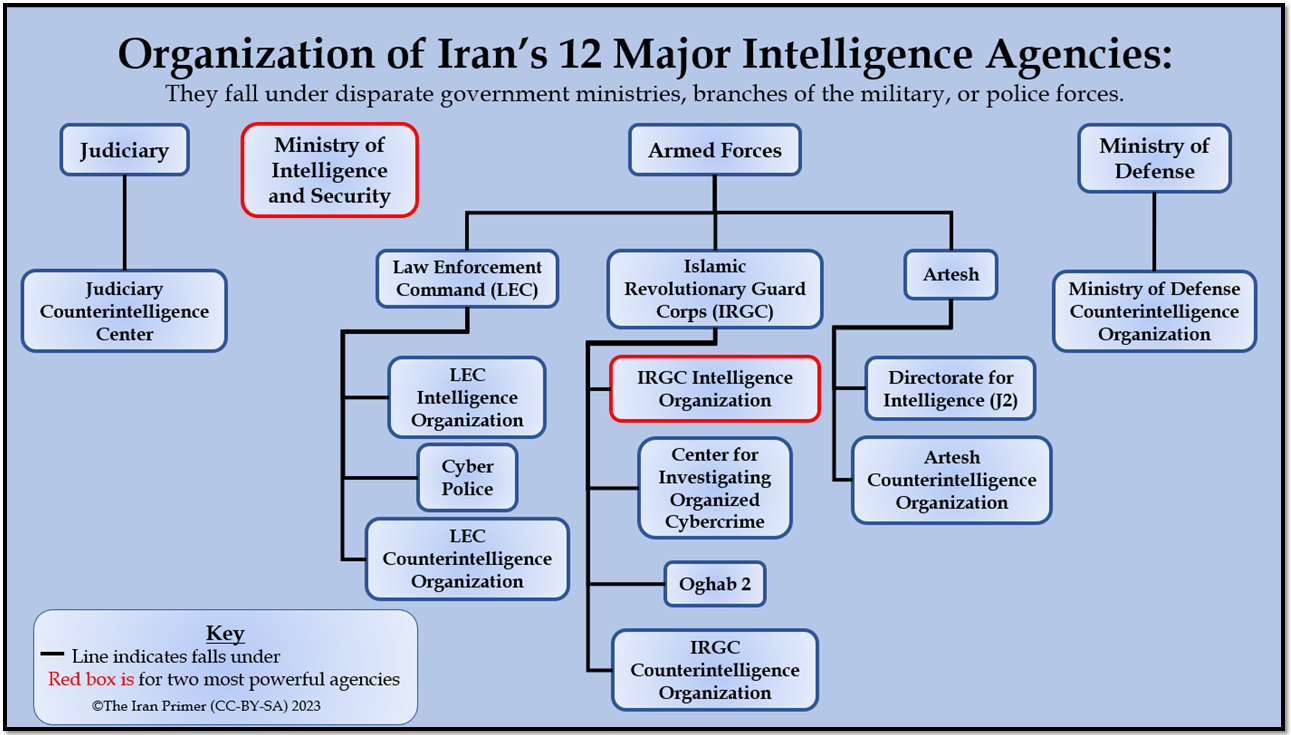

Since the 1979 revolution, Iran has spawned more than a dozen disparate intelligence agencies that engage in domestic and foreign surveillance. They separately report to different government ministries, branches of the military, or police forces. Under the constitution, the Supreme National Security Council, which develops national security policy, is charged with coordinating intelligence activities. The agencies are supposed to share information, but their missions often overlap, and they sometimes compete with—or undermine—each other over resources and influence.

Over four decades, the size, responsibilities, capabilities, and numbers of the intelligence agencies have grown substantially. “Iran’s intelligence services are capable of sophisticated operations worldwide to counter potential threats to the regime, its revolutionary ideology, and its interests,” the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) reported in 2019. Many agencies have their own counterintelligence (or information protection) organizations to prevent infiltration by foreign and domestic adversaries. Their operations are nominally coordinated by the General Office of Counterintelligence, which reports to the supreme leader as commander-in-chief.

The two most powerful intelligence branches are the Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS), which falls under the executive branch, and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps Intelligence Organization (IRGC-IO), which is part of the military. The two organizations have long vied for power and primacy.

Iran’s intelligence organizations have carried out four broad categories of operation:

Foreign operations: Iranian intelligence agencies have run operations—ranging from individual assassinations to mass bombings and cyberattacks—on six continents. In the 1980s, Iran was linked to suicide bombings carried out by proxies against U.S. embassies in Lebanon and Kuwait and U.S. Marine peacekeepers in Beirut in the 1980s. Iranian intelligence was cited by Argentina for the 1992 bombing of the Israeli Embassy and the 1994 bombing of a Jewish community center in Buenos Aires. In 2006, a U.S. federal court cited the Ministry of Intelligence and Security for funding and abetting the 1996 al Qaeda bombings of Khobar Towers, a residence for U.S. Air Force personnel in Saudi Arabia.

In the mid-2000s, the MOIS began an aggressive cyber campaign on government and private sector targets around the world. In 2011, the U.S. Justice Department announced that Iran had plotted to assassinate Adel al Jubeir, the Saudi ambassador to Washington. In 2020, Ethiopia arrested more than a dozen people linked to an alleged MOIS plot against the U.S., Israeli and United Arab Emirates embassies in Addis Ababa. In 2022, Microsoft charged that the MOIS was responsible for a massive cyberattack on Albania, which hosted an Iranian opposition group. The attack shut down several government websites.

Domestic counterintelligence: The Iranian agencies have targeted alleged Western and Israeli spy networks in Iran. Between 2009 and 2022, Iran reportedly identified and arrested dozens of CIA informants in counterintelligence investigations, although it rarely provided names of the alleged spies or proof of their operations. In 2011, the Ministry of Intelligence and Security announced the dismantling of a CIA spy network. It arrested 30 alleged operatives and identified 42 others linked to the U.S. network. One Iranian probe discovered a messaging platform used by the CIA to communicate with informants.

In 2019, the head of MOIS counterintelligence announced that the agency had arrested 17 alleged CIA spies in recent months. “Those who deliberately betrayed the country were handed to the judiciary,” the official told local media. “Some were sentenced to death and some to long-term imprisonment.” Iran claimed that it was the largest spy bust in years. In 2020, Iran executed two former Ministry of Defense employees charged with spying for the United States. In 2021, a senior CIA officer warned in a cable to Washington that Iran had devastated the U.S. intelligence network inside Iran, leaving few sources of information, The New York Times reported.

Arrest of foreigners in Iran: The Islamic Republic has detained dozens of foreign citizens since the revolution. Iran’s intelligence organizations have contributed to that count. Between 2007 and 2022, Iran’s intelligence agencies detained at least a dozen foreign nationals or permanent residents. The detainees faced charges ranging from espionage to threatening the regime. They held citizenship or had lived in Western countries, including the United States, Britain, France, Australia, Canada, Germany, Sweden, and Poland. Iran detained at least a dozen Americans in total between 2007 and 2022.

In 2013, the IRGC’s cyber intelligence wing detained Roya Saberi Negad Nobakht, a British-Iranian citizen, for “insulting Islamic sanctities.” In 2016, the United States and Iran swapped prisoners as Tehran and the world’s six major powers began implementation of their nuclear pact. Iran released four Americans, and the United States granted clemency to seven imprisoned Iranians in exchange.

But the swap did not mark an end to Iran’s longstanding practice of detaining foreigners. In 2016, the MOIS arrested Ahmadreza Jalali, a Swedish resident granted full citizenship after his arrest, reportedly because he would not spy on the European Union for Iran. In 2018, IRGC intelligence detained Morad Tahbaz, a U.S.-British-Iranian citizen, for alleged espionage. In 2020, IRGC intelligence detained Mehran Raoof, a British-Iranian labor rights activist. In 2022, the MOIS detained two French citizens, Cecile Kohler and Jacques Paris, for allegedly “promoting unrest and instigating chaos” during protests.

Pursuit of dissidents abroad: Since the 1979 revolution, Iranian intelligence agencies have also orchestrated an aggressive campaign to pursue, kidnap, prosecute or kill dissidents abroad. One early target was Ali Akbar Tabatabai, a diplomat during the monarchy who was murdered in his Maryland home in 1980. In the 1990s, Iranian intelligence was linked to the assassination of four Kurdish dissidents in Germany. In the mid-1990s, the MOIS was reportedly involved in the assassination of Reza Mazlouman, a former deputy minister of education under the monarchy, in Paris.

In 2010, the MOIS forced a passenger plane over Iranian airspace to land in southern Bandar Abbas and detained Abdolmalek Rigi, the leader of a militant Sunni group based in Sistan and Baluchistan province. In 2018, Denmark accused Iranian intelligence of plotting to murder at least one dissident based near Copenhagen. In 2021, the U.S. Justice Department charged four Iranians connected to the MOIS with plotting to kidnap Masih Alinejad, a Brooklyn-based dissident. In 2023, Australia claimed to have uncovered a surveillance plot against an Australian-Iranian citizen who was critical of the Islamic Republic. The following is a rundown of 12 Iranian intelligence agencies.

- Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS)

- IRGC-IO

- Center for Investigating Organized Cybercrime

- Oghab 2

- IRGC Counterintelligence Organization

- Artesh Directorate for Intelligence (J2)

- Artesh Counterintelligence Organization

- Law Enforcement Command (LEC) Intelligence Organization

- Cyber Police (FATA)

- LEC Counterintelligence Organization

- Judiciary Counterintelligence Center

- Ministry of Defense and Armed Forces Logistics (MODAFL) Counterintelligence Organization

Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS)

Mission: The MOIS is the primary civilian intelligence organization. In 1983, Parliament voted to create the MOIS for “gathering, procurement, analysis, and classification of necessary information inside and outside the country.” Its priority is domestic intelligence, such as surveilling dissidents and ethnic or religious opposition. But it also spies on Iranians abroad, collects intelligence on other governments, counters foreign intelligence plots, and works with allied intelligence agencies. All other intelligence agencies are technically required to share information with the MOIS, which chairs the Intelligence Coordination Council to coordinate the different organizations. The council manages “intelligence-related topics and operations” within the “legal boundaries of each agency” as well as “decisions on the responsibilities and powers of each agency.”

Numbers: As of 2019, the MOIS had approximately 30,000 officers and staff, according to a Pentagon estimate.

History: After the 1979 revolution, the Islamic Republic created the National Intelligence and Security Agency (SAVAMA). It was modeled on SAVAK, the shah’s ruthless intelligence service that had imprisoned and tortured many of the early revolutionaries. It also sponsored local komitehs—informal intelligence units—that spied on neighborhoods. In 1983, Parliament passed legislation creating the MOIS to combine SAVAMA and the komitehs. It began operations in 1984.

Significant operations: The MOIS has been linked to dozens of assassinations and attacks in and outside Iran. Among them:

- In 1992, MOIS was reportedly involved in the assassination of four Kurdish activists at the Mykonos restaurant in Berlin, Germany.

- Argentina charged that the MOIS and the IRGC were linked to two bombings in Buenos Aires by Hezbollah—in 1992, at the Israeli Embassy, killing 29, and, in 1994, at a Jewish community center, killing 86.

- Between 1988 and 1998, the MOIS reportedly assassinated dozens of dissidents, poets, and political activists—including the so-called “chain murders” of five writers in 1998—at home and abroad. In 1998, President Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005) ordered an investigation into the murders. The MOIS acknowledged responsibility for the chain murders but claimed that rogue agents were behind the attacks.

- In 2010, the MOIS forced a passenger plane over Iranian airspace to land and detained Abdolmalek Rigi, leader of Jundallah, a militant Sunni group based in Sistan and Baluchistan. Iran charged that Rigi was responsible for more than a dozen attacks in Iran that killed more than 150 and injured hundreds. He was subsequently executed.

- In 2018, European security authorities foiled an alleged MOIS plot to bomb the annual conference of the Mujahedeen-e Khalq (MEK) opposition group in Paris.

- In 2019, the MOIS was reportedly involved in the assassination of Masoud Molavi Vardanjani, a former defense ministry employee who charged the judiciary and security forces with financial corruption and assassinations, in Turkey.

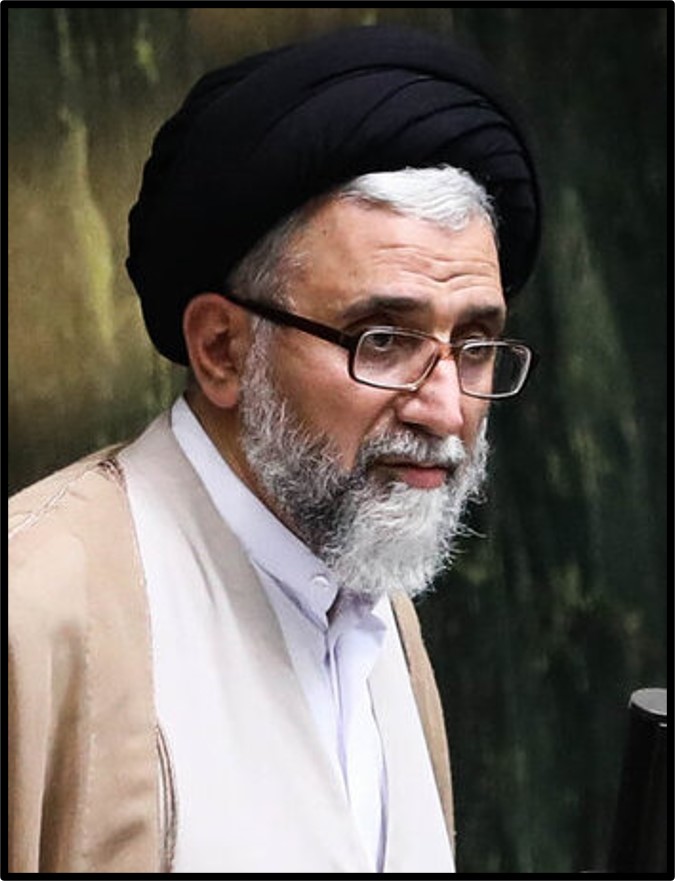

Leader: Hojatoleslam Esmail Khatib, a cleric with close ties to Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, was appointed minister of intelligence and security in 2021 by President Ebrahim Raisi. Khatib began his intelligence career with the IRGC in the early 1980s. He was the MOIS director for central Qom province in the 1990s. He later worked in the Office of the Supreme Leader Protection Organization and, in 2012, was appointed director of the judiciary’s counterintelligence organization.

During the 2022 protests, Khatib accused Western powers, Israel and Saudi Arabia of waging a “hybrid war” against the Islamic Republic by fomenting unrest and spreading propaganda in foreign media. “We will never sponsor acts of terrorism and insecurity in other countries, as Britain does, but we also have no obligation to prevent insecurity in those countries either,” Khatib said in a November 2022 interview. “Therefore, Britain will pay for its actions aimed at making Iran insecure.”

The president appoints the minister of intelligence and security, but the supreme leader must support the candidate. The MOIS minister falls under the executive branch, but is the only intelligence organization that answers to the president and supreme leader. By law, the minister of intelligence must be a cleric. Previous ministers of intelligence and security include:

Hojatoleslam Mahmoud Alavi (2013-2021): The mid-ranking cleric was a member of Parliament (1981-88 and 1992-2000) and deputy defense minister (1989-91). Alavi was the supreme leader’s representative to the Artesh (the conventional military) from 2000 to 2009. In 2009, he won a by-election to the Assembly of Experts, the 86-man council that selects the supreme leader. President Hassan Rouhani appointed Alavi to be minister of intelligence and security in 2013. In 2020, he was in charge when Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, the father of Iran’s nuclear program, was assassinated in a sophisticated plot widely attributed to Israel. The assassination exposed tensions between the MOIS and IRGC intelligence agencies. “The traitor who prepared the ground for the assassination” was “a member of the armed forces” whom the MOIS did not have the authority to interrogate, Alavi said in February 2021. Media affiliated with the IRGC blamed Alavi’s intelligence failure for Fakhrizadeh’s death.

Hojatoleslam Heydar Moslehi (2009-2013): The mid-ranking cleric was former representative to the IRGC for Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in the 1980s. He became Khamenei’s representative to the Basij paramilitary in the early 2000s. In 2005, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad appointed Moslehi adviser for clerical affairs. Moslehi headed the Organization for Islamic Endowments and Charities before he was named minister of intelligence and security in 2009. Ahmadinejad appointed Moslehi minister of intelligence and security, but the president reportedly demanded the minister’s resignation in 2011. In a reflection of tensions between Ahmadinejad and Khamenei, the supreme leader ordered that Moslehi remain in the post. In 2022, Moslehi left the MOIS and became a religious adviser to the IRGC.

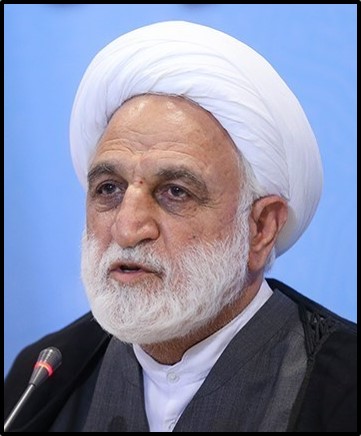

Hojatoleslam Gholam Hossein Mohseni Ejei (2005-2009): The mid-ranking cleric held senior positions in the MOIS and judiciary in the mid-1980s and 1990s. Ahmadinejad appointed him minister of intelligence and security in 2005, but the president fired Ejei in 2009 for opposing the appointment of Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei as first vice president. Ahmadinejad also reportedly blamed Ejei for failing to repress the 2009 Green Movement protests. Between 2009 and 2021, Ejei served in several judiciary positions, including prosecutor general of Iran, first deputy to then judiciary chief Sadeq Larijani, and judiciary spokesperson. Khamenei named him judiciary chief in 2021.

Hojatoleslam Ali Younesi (1999-2005): The mid-ranking cleric headed the Islamic Revolutionary Court of Tehran in the 1980s. President Khatami appointed him to be minister of intelligence and security in 1999. Younesi reportedly tried to limit corruption in the MOIS while he was minister. He left office at the end of Khatami’s term. In 2013, Rouhani named Younesi to be his adviser on ethnic and religious minority affairs.

In 2021, Younesi criticized the competition that flared between the different intelligence agencies after his time as minister. “Due to the competition of the intelligence services, the parallel work that happened in the [MOIS] and the new organizations… weakened the [MOIS],” he explained in an interview.

Younesi also called on the Supreme National Security Council to coordinate the agencies to protect Iran more effectively. “Those new and parallel organizations… instead of fighting influence, were busy controlling and fighting insiders,” he said, which allowed foreign intelligence agencies—especially the Mossad—to threaten the Islamic Republic. “We must go back to the past,” Younesi added. “Parallel work and competition should be ended, and the priorities of our internal services should be determined. The fight should be against the influence, not the internal elements who criticize and protest.”

Ayatollah Ghorbanali Dorri-Najafabadi (1997-1999): The senior cleric was a member of Parliament from 1980 to 1984 and again from 1992 to 1997. President Khatami appointed him minister of intelligence and security in 1997. He was reportedly forced to step down after the MOIS was linked to the so-called “chain murders,” though he denied responsibility. Najafabadi became prosecutor general of Iran from 2003 to 2009. Since 1991, he has been a member of the Assembly of Experts, which is popularly elected. Najafabadi has also been a member of the Expediency Council, which resolves disputes between Parliament and the Guardian Council, since 1997.

Hojatoleslam Ali Fallahian (1989-1997): The mid-ranking cleric headed the Special Court for the Clergy, which prosecutes clerics, in the 1980s. President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (1989-1997) appointed him minister of intelligence in 1989. Argentina cited him for a role in the 1994 bombing of a Jewish community center in Buenos Aires. Fallahian was also linked to assassination plots during his time in office. In 1996, Germany issued a warrant for Fallahian’s arrest over his alleged involvement in the 1992 assassination of four Kurdish activists at a restaurant in Berlin. Khatami replaced Fallahian—who reportedly opposed the reformist’s candidacy for president—with Najafabadi in 1997. Fallahian ran for president unsuccessfully in 2001 and was disqualified from running by the Guardian Council in 2013. He was a member of the Assembly of Experts from 1999 to 2016.

Ayatollah Mohammad Reyshahri (1984-1989): The senior cleric was chief justice of the Revolutionary Court in the early 1980s. Prime Minister Mir Hossein Mousavi appointed Reyshahri to head the new intelligence ministry in 1984. (Iran abolished the prime minister position in 1989.) Reyshahri allegedly pushed for the execution of thousands of political prisoners in the late 1980s. He was also reportedly involved in the effort to replace Grand Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri as Supreme Leader Khomeini’s successor. He was prosecutor general from 1989 to 1991. He was also appointed a special prosecutor for the clergy by Khamenei in 1990. Reyshahri ran for president in 1997 and received less than three percent of the vote. He was a member of the Assembly of Experts 1991 to 2007 and 2016 to 2022. He also served in other positions, including on the Expediency Council from 1997 to 2007. Reyshahri died in March 2022.

U.S. sanctions: In February 2012, the United States sanctioned the entire MOIS. “Today we have designated the MOIS for abusing the basic human rights of Iranian citizens and exporting its vicious practices to support the Syrian regime’s abhorrent crackdown on its own population,” said Under Secretary for the Treasury David Cohen.

In September 2022, the United States sanctioned Khatib and the MOIS for cyberattacks against the United States and its allies. The MOIS “directs several networks of cyber threat actors involved in cyber espionage and ransomware attacks in support of Iran’s political goals,” the Treasury Department said in a statement. It separately sanctioned Khatib again for the violent repression of protesters and other human rights abuses. Under Khatib, the MOIS cracked down on a large number of human rights defenders, women-rights activists, journalists, filmmakers, and members of religious minority groups, the Treasury Department said. In January 2023, the United States also designated Naser Rashedi, the deputy MOIS minister, for human rights abuses.

Insignia: The star-shaped insignia includes an eye with a globe as the pupil.

IRGC

The IRGC, established in 1979, protects the Islamic Republic from foreign and domestic adversaries. It became more powerful after Iraq’s invasion in 1980 and has since overshadowed the Artesh, or conventional forces. The IRGC is smaller, but it has access to more advanced weaponry and has more influence within government and the economy. For decades, the IRGC has played a role in quashing domestic uprisings. As of 2023, the IRGC had multiple intelligence wings. They included:

- IRGC Intelligence Organization (IRGC-IO)

- Center for Investigating Organized Cybercrime

- Oghab 2

- IRGC Counterintelligence Organization

IRGC-IO

Mission: The IRGC Intelligence Organization “exercises primary dominance over internal Iranian military intelligence responsibilities,” according to the DIA. The organization protects against terrorist attacks and foreign political interference. It represses demonstrations and unrest and monitors online activities of Iranians. The IRGC-IO counters influence operations from Iran’s Western adversaries. It has also detained dissidents, including Iranians, dual nationals, and foreigners. The IRGC-IO is technically required to cooperate with the MOIS.

History: The IRGC has conducted intelligence operations since it was created after the 1979 revolution. The intelligence unit began as the IRGC Intelligence Directorate. After unrest during the 2009 Green Movement, it was upgraded and renamed the IRGC Intelligence Organization.

The regime empowered the IRGC-IO over the MOIS after the disputed reelection of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005-2013) in 2009. The IRGC blamed the MOIS for failing to contain the Green Movement, which mobilized millions in nationwide demonstrations over alleged election fraud. After the protests, Ahmadinejad fired several top MOIS officials. Khamenei placed several former IRGC members—including Esmail Khatib, a former IRGC member—in top MOIS positions.

Significant operations:

- In the 1980s, IRGC intelligence ran military intelligence during the eight-year war with Iraq.

- In 1992 and 1994, Argentina charged the IRGC and the MOIS with involvement in two bombings by Hezbollah that went off at the Israeli embassy and a Jewish center in Buenos Aires.

- IRGC intelligence played a major role in repressing the 1999 student protests, the 2009 Green Movement as well as demonstrations in 2017-2018 and 2019 over economic grievances.

- In 2015 and 2016, the IRGC-IO detained a dozen fashion industry workers, reportedly after an order from Khamenei to limit Western cultural influence. They were later sentenced to prison terms from five months to six years.

- In April 2016, the organization detained Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, a British-Iranian project manager for the Thomson Reuters Foundation, for allegedly directing a “foreign-linked hostile network.” She was also accused of espionage and spreading propaganda against the government. Zaghari-Ratcliffe was released in May 2022.

- In February 2017, the IRGC-IO claimed to have prevented a terrorist attack by Mujahedeen-e Khalq (MEK), an exiled opposition group.

- In October 2019, the intelligence agency claimed to have uncovered an Israeli-led assassination plot against Maj. Gen. Qassem Soleimani, the IRGC Qods Force commander at the time.

- In October 2019, the IRGC-IO lured and detained Ruhollah Zam, dissident journalist who lived in France, at the Baghdad airport in Iraq. Zam was accused of inciting the 2017 protests. He was found guilty of “corruption on earth.” Zam was hanged in December 2020.

Leader: In June 2022, Brig. Gen. Mohammad Kazemi, the director of the IRGC Counterintelligence Organization, was appointed head of the IRGC-IO. The IRGC-IO chief is chosen by and reports to the supreme leader. The previous IRGC-IO chief was Hojatoleslam Hossein Taeb (2009-2022), a mid-ranking cleric who joined the IRGC in 1982. He was reportedly removed from the MOIS for investigating the son of President Rafsanjani in the 1990s. He commanded the Basij paramilitary in 2008 and had a leading role in the crackdown on the Green Movement protests in 2009. He was named the first head of the IRGC-IO in 2009. In February 2021, he bragged that the IRGC-IO had been “vigilant” in exposing foreign intelligence networks. After he was forced out, Taeb was named an adviser to Maj. Gen. Salami, the IRGC commander, in 2022.

U.S. sanctions: The United States has imposed dozens of sanctions targeting the IRGC and its proxies. It sanctioned the entire IRGC in October 2007 over proliferation concerns and again in June 2011 for human rights abuses.

In October 2017, the United States again sanctioned the IRGC as the world’s foremost state sponsor of terror. “Iran’s pursuit of power comes at the cost of regional stability, and Treasury will continue using its authorities to disrupt the IRGC’s destructive activities,” Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said in a statement. In April 2019, the United States designated the IRGC as a foreign terrorist organization. The Treasury Department sanctioned Kazemi in October 2022 for overseeing a “heightened crackdown on civil society across the country.” It again sanctioned Kazemi in April 2023 for the IRGC-IO's involvement in taking Americans and Iranian-Americans hostage.

Insignia: The IRGC-IO's emblem includes a hand holding a rifle over a globe and the Quranic verse: “Prepare for them [enemies] what you can by way of power/strength.”

Center for Investigating Organized Cybercrime

Mission: The Center for Investigating Organized Cybercrime tracks criticism of the government online and censors the internet. The organization cooperates with other intelligence organizations and the judiciary to protect the government against threats or plots conveyed on the internet.

History: The IRGC reportedly created the organization as the Center for Investigating Organized Crime in 2007. In 2015, the organization was upgraded and renamed the Center for Investigating Organized Cybercrime.

Significant operations:

- During the 2009 Green Movement, the center reportedly restricted websites and identified dissidents active online, some of whom were later detained.

- In a 2016 operation dubbed “Spider 2,” the Center for Investigating Organized Cybercrime claimed to have identified 170 Instagram users promoting “vulgarity.” It prosecuted more than two dozen people. The center monitored hundreds of pages during the investigation and collected personal information from each page, including followers, “likes,” comments, and connected social media accounts. The center also vowed to deal “decisively” with other Instagram users outside Iran but did not provide specifics. By the end of the year, the agency claimed to have detained or summoned 450 social media users—including on Instagram, Telegram, and WhatsApp—for “criminal modeling” and “insulting religious beliefs.”

U.S. sanctions: The United States sanctioned the Center for Investigating Organized Crime in November 2012.

Oghab 2

Mission: The Oghab 2 (or Eagle 2) organization is mandated to protect Iran’s nuclear program, including its personnel and equipment. Little is known about the organization, but it may report to both the IRGC and MOIS.

Numbers: As of 2012, Oghab 2 had up to 10,000 members, according to a research report by the Library of Congress.

History: The organization was reportedly created in 2005 by the IRGC. It increased in size in 2008 over concern about the assassinations of Iranian nuclear scientists.

IRGC Counterintelligence Organization

Mission: The IRGC Counterintelligence Organization is responsible for protecting against threats and infiltration by adversaries.

History: The IRGC counterintelligence wing was first mentioned in legislation that established the MOIS in 1983.

Leader: Khamenei appointed Brig. Gen. Majid Khademi, who had led the defense ministry’s counterintelligence organization, to head the unit in June 2022. In January 2023, Khademi condemned Iran’s adversaries for attempting to interfere in nationwide protests. “When our officials neglected the youth, the enemy used perception and cognitive warfare… to make them disappointed about the future, their beliefs, and ideals and make them distrustful,” he said in a speech commemorating the third anniversary of the assassination of Qassem Soleimani.

Artesh

Directorate for Intelligence (J2)

Mission: The J2 conducts tactical intelligence and counterintelligence operations. It oversees intelligence and security affairs in the Artesh, or conventional military. It reportedly includes members from diverse military branches.

Artesh Counterintelligence Organization

Mission: The Artesh Counterintelligence Organization is responsible for protecting against threats and infiltration by adversaries.

History: The Artesh Counterintelligence Organization was established in 1983 during the eight-year war with Iraq.

Leader: Brig. Gen. Mohammad Hassan Habibian headed the Artesh Counterintelligence Organization at least between 2013 and 2018. He has long warned that technology changed the nature of conflict and the tools of adversaries. Habibian said that Iran’s adversaries had tried to prevent the Islamic Republic from “acquiring new knowledge and technology,” but claimed that his organization had helped to mitigate those threats.

Law Enforcement Command (LEC)

The LEC is the national police force. Established in 1991 as the Law Enforcement Forces (LEF), it combined disparate police groups into one organization. The LEF was overseen by the Interior Ministry. In December 2021, Khamenei upgraded and renamed the LEF the Law Enforcement Command (LEC). The LEC was placed under the Armed Forces General Staff, which also oversaw the IRGC and Artesh. By 2023, the LEF had multiple intelligence wings. They included:

- LEC Intelligence Organization

- Cyber Police (FATA)

- LEC Counterintelligence Organization

LEC Intelligence Organization

Mission: The LEC Intelligence Organization collects information on crimes and social violations including theft, corruption, and smuggling. It monitors organized crime through neighborhood informer networks throughout Iran.

History: The LEC Intelligence Organization was preceded by the Public Security and Intelligence Police (PAVA) under the LEF. The PAVA intelligence branch reportedly grew after the 2009 Green Movement. When Khamenei established the LEC in 2021, the PAVA intelligence branch was upgraded and renamed the LEC Intelligence Organization.

Significant operations:

- In March 2022, the organization exposed an alleged arms smuggling network and detained five people. It claimed that they had smuggled dozens of weapons into Iran through western Khuzestan province, which borders Iraq.

- In September 2022, the LEC Intelligence Organization participated in the crackdown against protesters. In December, the Tehran branch detained four people who were allegedly the “main perpetrators” of unrest. “The security and peace of the people is the red line of the police,” the organization said.

- In January 2023, the LEC Intelligence Organization detained 13 people. They had been commemorating the deaths of protesters killed by the government during demonstrations that began in September 2022. It claimed that the people were “instigating the enemy networks” to “create chaos and insecurity.”

Leader: Brig. Gen. Gholamreza Rezaian, who had previously led the LEF Economic Security Police, was named head of the LEC Intelligence Organization in January 2023. The LEF Economic Security Police was concerned with economic crimes such as money laundering, smuggling, tax evasion, and other financial violations.

U.S. sanctions: The United States sanctioned the entire LEF for human rights abuses in 2011 and 2012. The 2011 sanctions were issued under Executive Order 13553, which authorizes sanctions on individuals and entities with respect to serious human rights abuses by the Iranian government. The 2012 sanctions were issued under Executive Order 13606, which authorizes designations with respect to grave human rights violations by the government, notably for censorship as well as monitoring or tracking internet usage.

Cyber Police (FATA)

Mission: Iran’s national Cyber Police investigates phishing, hacking, fraud, forgery, destruction of data, defamation, and other cybercrimes. FATA also monitors online activists, internet service providers, internet cafes, and information sector companies. It suppresses dissidents and monitors criminal cyber activities online and on social media. It has stations in dozens of cities across all 31 provinces.

History: The organization was reportedly created in 2011 in response to growing cybercrimes. Brig. Gen. Ismail Ahmadi Moghadam also cited social media used for “spreading of rumors and recognition of anti-government groups” during the 2009 Green Movement protests.

Significant operations:

- In October 2012, FATA detained 35-year-old blogger Sattar Beheshti for criticizing the regime. He was reportedly tortured and died in detention days later.

- In March 2013, FATA announced new internet café regulations, which included restrictions on eligible internet providers, the age required to own a café, and mandatory information collection on customers. It also blocked more than 1,900 websites and shut down 10 internet cafes.

- Between mid-2014 and late 2015, FATA had detained 53 people for allegedly operating pro-ISIS web pages.

- In May 2021, FATA claimed to have found fraud before the presidential election. “We monitor and follow the destruction of candidates, insults… defamation… or the publication of people’s privacy.”

- After the outbreak of COVID-19, FATA reported monitoring more than 3,000 social networks because people “were trying to create tension” in society and “destroy the morale of the people by publishing truncated, fake [video] clips.” It filed at least 700 cases with the judiciary against alleged offenders. It claimed that 56 percent of investigations related to COVID-19 concerned rumors and 17 percent included fake statistics.

- In 2022, the Cyber Police reported that people between the ages of 18 and 30 were responsible for 80 percent of cybercrimes.

Leader: Vahid Mohammad Naser Majid, the former deputy chief, was appointed head of the FATA in 2019. In December 2022, Majid said that internet fraud cases had increased by 37 percent over the previous year.

U.S. sanctions: In February 2013, the United States sanctioned FATA for human rights violations. In October 2022, it designated Majid for his role in internet restrictions during nationwide protests. Majid “leveraged the Iranian Cyber Police to regularly monitor Iranian Internet users, filter websites, and block content the Iranian government finds objectionable,” the Treasury Department said. Majid dismissed the sanctions. Sanctions had “no effect on our activities,” he said in November 2022.

LEC Counterintelligence Organization

Mission: The LEC Counterintelligence Organization is responsible for protecting against threats and infiltration by adversaries.

History: The Counterintelligence Organization was established along with the LEF.

Leader: Brig. Gen. Mohsen Fathizadeh, the deputy LEF coordinator, was appointed head of the LEF Counterintelligence Organization in December 2019.

Judiciary

Judiciary Counterintelligence Center

Mission: The Judiciary Counterintelligence Center is responsible for protecting against threats and infiltration by adversaries.

History: The judiciary established the center in February 2001. A Parliament commission proposed to upgrade and rename it the Judiciary Counterintelligence Organization in December 2022. The plan would expand the center’s powers and authorities. The goal was to better manage and consolidate the judiciary’s security and intelligence institutions. As of early 2023, the plan had not yet been implemented.

Leader: Hojatoleslam Ali Abdallahi, a former judge in the Special Court for the Clergy, was appointed head of the judiciary Protection and Information Center in July 2019. Abdallahi said that the supreme leader called on him to cleanse the judiciary of corruption. In November 2022, he charged that nationwide unrest was caused by “unhealthy and ineffective people being placed” in the wrong government positions.

Ministry of Defense and Armed Forces Logistics (MODAFL)

MODAFL Counterintelligence Organization

Mission: The Ministry of Defense and Armed Forces Logistics Counterintelligence Organization is responsible for protecting against threats and infiltration by adversaries.

Leader: Rahim Yaqoubi, a former deputy head of the IRGC Counterintelligence Organization, was appointed head of the MODAFL Counterintelligence Organization in July 2022.

Connor Bradbury is a Senior Program Assistant at the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Picture Credits: 1983 U.S. Embassy Beirut Bombing (public domain); MOIS Insignia (public domain); Esmail Khatib via Mehr News Agency (CC BY 4.0); Gholam Hossein Mohseni Ejei via Tasnim News (CC BY 4.0) Ali Fallahian via Mehr News Agency (CC BY 4.0); IRGC-IO Insignia via Aparat; Kazemi via IRNA (CC BY 4.0); Center for Investigating Organized Cybercrime Insignia via Tasnim News (CC BY 4.0); LEC Intelligence Organization Insignia via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0); Cyber Police Insignia via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)