Mahsa Alimardani is a researcher at ARTICLE19, an international human rights organization focused on freedom of expression and information. She is also a doctoral student at the University of Oxford’s Oxford Internet Institute.

Since the beginning of the Internet in the mid-1990s, how has Iran limited public access to it?

Iran’s approach to monitoring, censoring and controlling the Internet has slowly developed since the mid-1990s. The authorities have mostly been reactive. The Internet was first introduced through research institutes. It became available commercially when traditional print media was under tight censorship. During the presidency of Mohammed Khatami (1997-2005), his reformist coalition clashed with conservative elements within the ruling establishment, especially the Revolutionary Guards and the Judiciary, which often led the charge of repression and censorship.

Iran entered an era of extra-legal punitive measures against newspapers and journalists, especially those supporting the liberalizing ideals promoted by Khatami. Many writers, journalists and intellectuals started going online during this period, which became known as the “Blogistan” era. Writing online became a form of resistance against the controls over traditional media.

In the early years of “Blogistan” – the late ‘90s and early ‘00s – there was a substantial amount of free expression. But then the authorities started to catch on and monitor the space. The first instances of Internet censorship occurred in 2002, as hundreds of websites were blocked in an increasingly systematic and organized fashion.

Censorship increased dramatically during and after the June 2009 presidential election. The race was the first large-scale national event in Iran to be extensively promoted and followed on the Internet and on social media. With public excitement about the reformist candidates running high, the authorities blocked both Twitter and Facebook in the weeks leading up to the election.

Incumbent President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a conservative, was declared the winner. But the defeated candidates and many others claimed widespread vote fraud. During the two weeks following the election, millions of Iranians took to the streets to protest the result. The government enacted a short nationwide Internet shutdown to quell the massive demonstrations. It was the first of many shutdowns or mass disruptions, which became common tactics of the state during protests.

Incumbent President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a conservative, was declared the winner. But the defeated candidates and many others claimed widespread vote fraud. During the two weeks following the election, millions of Iranians took to the streets to protest the result. The government enacted a short nationwide Internet shutdown to quell the massive demonstrations. It was the first of many shutdowns or mass disruptions, which became common tactics of the state during protests.

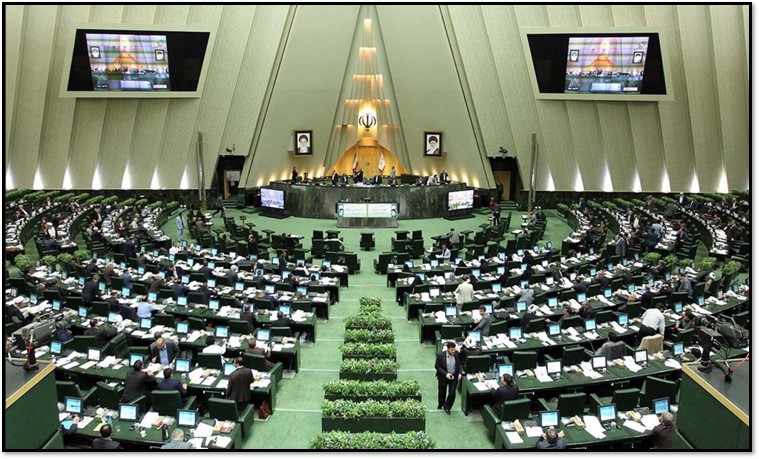

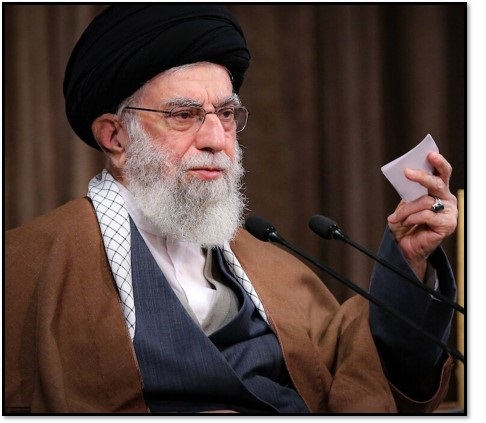

Plans for regulations to centralize and control the Internet were already in the works prior to the 2009 election. But the protests against the election results spurred key institutions to assume oversight of cyberspace. Parliament ratified the Computer Crimes Law, and, soon after, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei decreed the creation of an Internet policy body, largely controlled by himself, known as the Supreme Council of Cyberspace.

What popular sites are blocked? Since when, or under what presidency? Why?

The Islamic Republic started blocking websites and social media platforms to stymie protests and to suppress criticism of the government. But it has also blocked services to censor content that it deemed inappropriate or un-Islamic.

Iran Election news:

— Negar Mortazavi (@NegarMortazavi) June 17, 2021

Group of young activists are on Clubhouse discussing the importance of political participation, trying to convince undecided voters to participate and vote for Hemmati to prevent a Raisi presidency.https://t.co/Zj3yfV1t1N pic.twitter.com/DI8ulhvPsd

Youtube was temporarily blocked in 2006 over a video of an Iranian soap opera star that was deemed immoral. It was temporarily blocked again amid the protests against the 2009 presidential election results. YouTube was blocked again in 2012 because it hosted an inflammatory video about the Prophet Mohammed.

Twitter and Facebook were blocked in the runup to the 2009 elections. Telegram was blocked in April 2018, after temporarily being blocked alongside Instagram during the nationwide protests over economic grievances in late 2017 and early 2018.

Clubhouse was unofficially blocked in early 2021 after a surge in popularity among Iranians inside the country and in the diaspora. Users from across the political spectrum – principlists, reformists and even those seeking regime change – discussed domestic politics, foreign policy, human rights and other sensitive topics in virtual rooms with thousands of people. This relatively free flow of conversation (rooms hosted by Iranian officials had some restrictions) may have spurred authorities to pressure Iran’s Internet Service Providers (ISPs) to largely block access to the application.

Overall, Iran’s presidents have had little influence over censorship policies. Social media platforms were blocked under both Ahmadinejad (2005-2013), a hardliner, and Hassan Rouhani (2013-2021), a centrist backed by reformists. The Islamic Republic’s core “nezam,” or system, headed by the Supreme Leader, has prevailed on cyberspace issues since the 2000s.

In July 2021, Parliament introduced a new bill that could further limit public access. The legislation is called “Cyberspace Users Rights Protection and Regulation of Key Online Services.” In February 2022, Parliament tried to ratify the central elements of the bill. What does it do? What does the bill mean by “protection”?

The bill is intended to help the state further centralize and control the Internet within Iran, in part by asserting power over foreign technology companies. The bill calls for several actions but does not specify how they would be carried out. The language in the bill suggests that the authors lack an understanding of the technical logistics required to implement what it proposes.

Many Iranians use one if not several VPN applications on their cell phones, tablets and computers. The VPN market in Iran is worth an estimated $21 million a year. Some VPNs are supported by grants funded by foreign governments and foundations, such as Psiphon. The company shared its usage data with ARTICLE19 for 2021, which showed that some 1.15 million users in Iran used the platform.

The bill does not indicate if authorities have developed new techniques to block VPNs or how strictly they will penalize VPN users. They also plan to throttle popular unblocked foreign social media like WhatsApp and Instagram until local alternatives are made available.

To avoid the crackdown, companies that operate social media networks and provide other web services would be required to cooperate and create offices in Iran that would allow them to remain unblocked or unthrottled.

The “protection” element refers to the regime’s intention to “shield” Iranian users from content that it deems “nefarious,” un-Islamic, Western, or promoted by “enemy” elements. (See here for more analysis of the bill.)

Authorities began to quietly implement parts of the bill after it was introduced in July 2021 and fast-tracked for approval. For example, they throttled and lowered international bandwidth, hindering users’ ability to load Instagram. In February 2022, lawmakers ratified the bill. But the vote was overturned by Parliament's regulations department.

What impact might the bill have on public access to information from outside Iran?

The impact would depend on how strictly the bill is implemented and enforced. In the most draconian scenario, the National Information Network, Iran’s local Internet, would dominate what Iranians can see online, creating steep obstacles for access to the international Internet. Nearly all Iranians would be forced to rely on an insecure, heavily censored and monitored Internet. At the very least, the bill will add a new element of risk in the cat and mouse game of circumventing online controls and surveillance.

Who would control or supervise content? Or how would supervision or “protection” work?

The bill, if approved by the hardliner-dominated parliament, would empower the Supreme Regulatory Commission (SRC) – an almost dormant arm of the Supreme Council of Cyberspace (SCC) – to implement and enforce its regulations. The SRC has historically played an advisory role within the SCC, established in 2012 to develop Internet policies. The bill delegates responsibilities and powers to the SRC that overlap with legal responsibilities of the Ministry of Information and Communications Technology (ICT), the Committee Charged with Determining Offensive Content (CCDOC), and even the SCC itself.

The repurposed SRC would have 21 members, including three members of Parliament who would have non-voting status. It would be headed by the director of the National Center of Cyberspace (the executive arm of the SCC) and would be dominated by unelected appointees of Supreme Leader Khamenei.

The SRC’s voting members would include three members of the SCC and representatives from or heads of the:

- National Center of Cyberspace

- Office of the Prosecutor General

- General Staff of the Armed Forces

- Passive Defense Organization

- Revolutionary Guards

- Police

- IRIB (state broadcaster)

- Islamic Propagation Organization

- Intelligence Ministry

- ICT Ministry

- Culture Ministry

- Industries Ministry

- Economy Ministry

- Vice Presidential Office for Science and Technology

- ICT Guild Organization

Of the 18 voting members of the SRC, 12 would be direct or indirect appointees of the Supreme Leader, and five would be representatives of security agencies or the military. Members of civil society and representatives of the general public would have little, if any, say in its operations and would not be able to hold it accountable for its actions.

The legislation also charges the SRC with regulating “Key Online Services” and issuing, renewing and annulling permits. The SRC itself would determine what should be classified as a “Key Online Service.” Transparency and accountability would be limited because the SRC would be responsible for both policymaking and enforcement.

The commission would also regulate monopolies for all ICT-related markets, including communications and online services. Currently, the Communication Regulatory Authority (CRA), which operates under the ICT Ministry, regulates prices in the communications sector. Transferring the responsibility to an agency dominated by unelected officials opens the door to even wider to corruption and conflicts of interest, especially since some members of the proposed commission are major stakeholders in Iran’s telecom industries (explained in detail in ARTICLE19’s 2020 “Tightening the Net” report).

The bill also mandates the commission to develop rules and mechanisms for “user authentication and identification.’’ It grants the SRC the power to regulate the distribution and application of VPNs and proxy services.

Given the heavy censorship already imposed, VPNs and other proxy networks have long been a popular tool among the public. In 2020, Iranian officials touted the idea of introducing “legal VPNs.” The discussion has been interpreted by many experts following Internet policy as the introduction of a multitiered system that would rank users and provide different levels of Internet access based on their age and profession. In an interview during his 2021 presidential campaign, Ebrahim Raisi expressed support for tiered access.

The bill grants the commission a wide range of other powers and responsibilities, including:

- introducing regulations for “protecting children and family institutions” online

- regulating and overseeing e-governance and e-banking projects

- overseeing the activities of Iranian state and government officials on unlicensed foreign platforms

- regulating personal, business, and governmental applications of “Key Online Services”

- regulating applications of “foreign software required for development and expansion of local services”

- regulating advertisement on unlicensed foreign platforms

- regulating, monitoring, and evaluating performance of entities offering communication and IT services

- regulating international cyberspace collaborations

- introducing regulations and guidelines for user privacy, cyber literacy, online advertisement, and copyrights

- reporting any infringement of the legislation to relevant judicial bodies

- delivering regular reports on Iran cyberspace, IT services, and “Key Online Services” to the SCC, Parliament and other relevant bodies

Would Iranians still be able to use VPNs to access blocked websites?

The bill includes a ban on all business activity related to development, distribution, reproduction, and sale of “illegal” VPNs and proxies, “mass distribution” of VPNs, or “illegal distribution” of tools that can provide users with access to “illegal blocked services.” Any violation of the article would be considered a sixth-degree criminal offense punishable by up to two years in prison and/or a fine.

What is the state of the “National Information Network,” Iran’s alternative to the Internet?

Confirmed: Internet access is being restored in #Iran after a weeklong internet shutdown amid widespread protests; real-time network data show national connectivity now up to 64% of normal levels as of shutdown hour 163 📈📵#IranProtests #Internet4Iran

— NetBlocks (@netblocks) November 23, 2019

📰https://t.co/XQmiaOlRL7 pic.twitter.com/eimWEIEmrI

In 2012, Iran initiated development of the National Information Network (NIN), a domestic Internet infrastructure that would be more secure from foreign cyberattacks and potentially disconnected from the global Internet. Some elements of the NIN have already been launched, including national infrastructure for banking and payment methods. It has been used to temporarily shut down Internet access during protests and unrest. The most notable was the week-long shutdown Iran experienced in November 2019, following nationwide protests spurred by fuel price hikes. But the development of the NIN has not yet resulted in any long-term disconnection from the global Internet.

The NIN allows authorities to monitor content based on political, cultural, and religious criteria. Oversight of data and traffic on this network limits privacy and data protection for Iranian users. Since Rouhani’s first term (2013-2017), authorities have been much more aggressive in driving Internet users toward domestic platforms and reducing access to content and services available through the global Internet. The government has subsidised many applications built on the NIN.

By Rouhani’s second term (2017-2021), authorities introduced penalties and required companies and entrepreneurs developing the NIN to shift onto the nationalized platforms, servers and infrastructure.

After the United States pulled out of the nuclear deal in 2018, international tech companies increasingly over complied with U.S. sanctions to avoid penalties. Subsequently, more users, especially developers who depended on developer tools hosted by Google and Amazon increasingly found these tools blocked. They have been forced to rely on tools tied to or hosted by the NIN.

The Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” campaign, including the reimposition and expansion of wide-ranging sanctions on Iran, provided a convenient justification for Iranian officials to call for the NIN’s expansion. Initially, only hardliners such as Abolhassan Firoozabadi, secretary of the SCC, claimed that the United States might cut Iran off from the international Internet by enforcing sanctions – a highly unlikely if not impossible scenario. By June 2019, even officials in the Rouhani government, including Azari Jahromi, the ICT minister, were echoing Firoozabadi’s warning and advocating for the NIN. “We are preparing for scenarios where the internet will be cut off,” Jahromi explained in 2019.

What happens to foreign platforms that refuse to comply with government regulations?

The bill requires international tech companies to have a legal representative in Iran to comply with local laws and cooperate with the government in surveilling users and censoring online spaces. In practice, however, most international tech companies, especially firms with ties to the United States, would not accept these demands, due to the far-reaching U.S. sanctions in place against the Islamic Republic.

Platforms that refuse to comply with the rules would be subject to bandwidth throttling until domestic alternatives are created. At that point, they are likely to be fully censored, pushing nearly all users onto the Iranian platforms on the NIN.

The bill signals a significant shift toward a further crackdown, since such throttling – while not uncommon – was not previously acknowledged as government policy. In 2021, access to three major social media platforms and instant messaging services – WhatsApp, Instagram and Clubhouse – was disrupted in Iran using the technique.

What does Iran’s constitution, approved in a 1979 referendum, say about freedom of speech?

The constitution ostensibly protects freedom of speech but allows for many exceptions. For example, article 24 states that “publications and the press have freedom of expression,” but includes a broad caveat that there should be no “infringement of the basic tenets of Islam or public rights.”

Other articles in the constitution undermine the already weak guarantee. In particular, article 40 allows for the restrictions of rights if their exercise is deemed “injurious to others” or “detrimental to public interests.”

The constitution’s protections are also curtailed by several provisions of the Islamic Penal Code. The code, ratified in 1991, criminalizes the exercise of freedom of expression through vaguely worded and broadly defined “offenses,” including “spreading propaganda against the system,” “insulting Islamic sanctities,” and “insulting the Supreme Leader.” These provisions are frequently used to stifle dissenting voices. If the protection bill is implemented, the penal code could be applied extensively to private conversation and a variety of private activities online.