Iran is lagging behind other Middle Eastern countries in expanding relations with China, according to a new study by Lucille Greer and Esfandyar Batmanghelidj. In June 2020, the “Final Draft of Iran-Strategic Partnership” circulated on Iranian social media and caused a firestorm in Iran among the general public and politicians. The 18-page document, which appeared to be leaked, stoked fears that China was deepening relations with Iran through secret deals on oil, communications technology, and military ties.

Yet Iran’s ties with China would still be limited compared to Beijing’s engagement with other countries, such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, which are Iran’s main regional rivals. China “has proven reluctant to deepen its economic commitment to Iran given the constraints of the domestic market, U.S. sanctions, and regional tensions which introduce steeper tradeoffs for any Chinese investments,” according to Greer and Batmanghelidj.

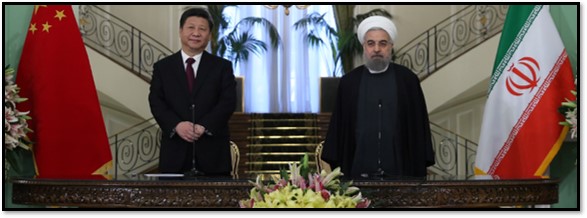

Chinese President Xi Jinping with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani in January 2016

The latest negotiations between Iran and China were a continuation of an earlier deal, the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, which was signed in January 2016. The new draft agreement does not create a new alliance or change the balance of power in the Middle East. The following are excerpts from the paper, originally published by the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

CHINESE ECONOMIC ENGAGEMENT IN IRAN

Over the last two decades, China has emerged as Iran’s leading trade partner. China has been Iran’s largest oil customer and today remains the only country purchasing Iranian oil in defiance of U.S. sanctions. China is also a major industrial supplier to Iran, having displaced Europe in 2008 as the largest supplier of industrial parts and machinery that are used by Iran’s growing manufacturing sector. In this regard, Iran’s trade partnership with China resembles the partnership enjoyed with Europe prior to the imposition of multilateral sanctions in 2008. Foreign exchange revenues earned through the sale of oil are spent on high-value industrial inputs as well as finished goods such as consumer products.

Chinese exports to Iran rose from $2.5 billion in 2004 to $14 billion in 2018, a significant increase in total magnitude. But in relative terms, this growth, equivalent to an annual rate of 16.9 percent, reflects the regional norm. The average annual growth rate of Chinese exports to Pakistan (15.6 percent), Saudi Arabia (16.1 percent), and Turkey (16.8 percent) are comparable to the growth seen in Iran. Growth in Pakistan (15.6 percent) and the UAE (12.9 percent) are slightly lower given greater penetration of Chinese goods at the beginning of the period. Growth of Chinese exports to Iraq measures a staggering 39.0 percent, reflecting growth from a very low level of exports.

Between 2010 and 2014, Chinese exports to Iran grew at an annual rate of 29 percent, even as the international community sought to tighten sanctions on Iran. The perception of China’s steadfast and strategic commitment to Iran’s economy is largely left over from this period. Exports to Iran peaked in 2014 at $24 billion, making Iran the region’s second largest destination for Chinese exports after the UAE. Since 2014 however, the trade relationship between China and Iran has deteriorated. Exports fell by an annual average of 11.5 percent in the subsequent four years, despite Iran benefiting from increased sanctions relief in this period. By comparison, China’s trade with the other states included in this study has remained relatively constant.

The decline in Iranian oil sales to China has also created a ceiling for the overall trade relationship, with Iran unable to effectively finance the resulting trade deficit due to deteriorated banking ties and limited access to foreign currency reserves. This financial limitation is among the factors that explain why Chinese exports to Iran have fallen over the last year, adding to the malaise in China-Iran trade.

Stagnation in Foreign Direct Investment

Given the malaise in the China-Iran trade relationship, it should be no surprise that Chinese investments in Iran have languished. Like trade, Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) grew considerably between 2004 and 2018. Although total FDI stock is far below the levels that have made headlines in recent years, a reflection of the fact that Chinese investment commitments only rarely result in actual flows. Chinese FDI stock in Iran rose from $468 million in 2004 to $3.23 billion in 2018. In absolute terms, this growth may appear to support the perception of Iran’s economic dependence on China. But the total makes Iran just the third largest recipient of Chinese FDI among the countries included in this study, after the UAE ($6.23 billion) and Pakistan ($4.24 billion), a ranking consistent with its position as the third largest economy in the same group.

Given the long timeline of many energy and infrastructure projects, it can be difficult to track China’s economic engagements from the announcement of a new contract through to its implementation. The China Global Investment Tracker Project, a joint initiative of the American Enterprise Institute and the Heritage Foundation, compiles data on Chinese investment and construction contracts since 2005 (including those projects that are confirmed in public communication of one of the contracting parties, whether in the form of a press release, annual report, or regulatory disclosure). While the tracker’s data diverges somewhat from the official data, it is still clear that China is absolutely and relatively underinvested in Iran, with Iran having received the least direct investment among all of the major economies in the Middle East.

No Belt, No Road

One of the visible signs of increased Chinese economic presence in Iran was the influx of Chinese executives and laborers, particularly during the peak of China’s economic engagement of Iran between 2008 and 2014. The presence of Chinese nationals was taken to confirm that major investments were proceeding and that Iran, given the gift of its geography, was taking a central place in China’s Belt and Road Initiative. But the number of Chinese laborers dispatched to work on infrastructure projects in Iran averaged just 1,300 between 2011 and 2018, the lowest level among the six countries included in this study. By comparison, Saudi Arabia hosted 19,000 Chinese laborers on average in the same period.

Looking across trade, foreign direct investment, financing, and labor, it is clear that Iran is neither a Chinese priority nor dependency. China has sought to expand its economic footprint across the Middle East, and it has proven reluctant to deepen its economic commitment to Iran given the constraints of the domestic market, U.S. sanctions, and regional tensions which introduce steeper tradeoffs for any Chinese investments.

Iranian policymakers are also aware of the limitations facing the partnership, including concerns over economic dependence and the inability of Chinese investment to fully compensate for reduced trade and investment from the west. But what they are seeking now is a reset in the economic relationship, furnished by a fuller implementation of the CSP that would see Chinese trade and investment restored to levels in line with the size of the Iranian economy and therefore bring it into balance with China’s economic commitments elsewhere in the region.

Given the continued tensions between Iran and Saudi Arabia, any failure to strike such a balance could threaten the viability of China’s wider economic plan in the Middle East and the continued flow of cheap energy to the Chinese economy. In this regard, the economic anxieties plaguing the China-Iran relationship, reflected in the new push around the CSP, are directly linked to questions of regional security.

CHINESE SECURITY COOPERATION WITH IRAN

If China is careful and calculated with its multifaceted economic interactions in the Middle East, it is highly risk averse when it comes to the security dimension. China has many geopolitical fronts where security is a priority – Taiwan, Hong Kong, the South China Sea, North Korea, to name a few – but they all fall within its East Asian sphere of influence. None of these fronts are located in the Middle East.

Militarization has been part of the Chinese agenda under Xi Jinping, and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) have made long strides with the launch of China’s first and second aircraft carriers, the Liaoning and the Shandong. China’s first foreign military base located in Obock, Djibouti sits on the strategic Bab el-Mandeb Strait between the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, and is only a short sail away from the Gulf of Oman and the Strait of Hormuz. But this logistical base is insignificant compared to the military presence of other countries, particularly the United States.

Joint Military Exercises

Over the past ten years, China has only conducted three joint drills and technical port calls with Iran. The first was in 2014, when two Chinese warships, including the guided-missile destroyer Changchun, visited Port Bandar Abbas and conducted joint drills focusing on safety at sea and anti-piracy. This occurred after the Iranian Navy helped liberate a Chinese cargo ship from pirates in the Gulf of Aden.

The second was in 2017, when one Iranian destroyer and two Chinese destroyers conducted four days of naval drills in the eastern portion of the Strait of Hormuz. The third drill occurred in December 2019 as tripartite exercises with Russia. Named the “Marine Security Belt,” these drills were conducted in the Gulf of Oman and Indian Ocean. In all instances, Chinese state media sources were more restrained in their commentary on what they called “routine exercises,” while Iranian state media sources trumpeted them as proof of a formidable partnership. These attitudes towards the drills are indicative of the very lopsided relationship between Beijing and Tehran, which Iran is now trying to correct by guaranteeing Chinese military participation going forward in the CSP.

Arms Sales

Arms sales to Iran are impeded by the UN multilateral sanctions that have been imposed since 2006 and the shifting variety of U.S. unilateral sanctions that included weapons beginning in 1984. Even though the 2006 multilateral sanctions were motivated by nuclear weapons development and do not name conventional weapons, they have nevertheless stunted Tehran’s access to the conventional weapons market.

China previously made inroads in weapons sales to Iran during the Iran-Iraq War which represented the highest period of arms transfers from China to Iran. China had sold $3.3 billion of military equipment to Iran by the end of the war, while selling equipment to Iraq as well.

Since 2000, Iran has imported 930 anti-ship missiles, 1,750 portable surface-to-air missiles, six surface-to-air missile systems, three air search radars, 150 armored personnel carriers, and nine catamaran missile boats from China.

In value alone, it outstrips every partner other than Pakistan. However, China has not exported any unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), or drones, to Iran. China has two series of drones on the international arms market: The Wing Loong I and II and the Chang Hong series, the most relevant of which is the CH-4. The CH-4 drone is a medium-altitude, long endurance armed drone comparable to the U.S.-made Predator series, but cheaper.

China has, on the other hand, exported Wing Loong and CH-4 drones to Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Iraq, and Pakistan. Iraq has applied the technology to combating the Islamic State, while Saudi Arabia and the UAE have used CH-4 drones in their campaign against Iranian-backed Houthis in Yemen, a fact sure to vex Iran.

CONCLUSION

There is no denying the economic and political significance of the CSP between China and Iran. But as the analysis presented in this paper makes clear, the extent of economic and military cooperation between the two countries has been limited, at least in relation to other countries in the region; a fact that speaks to how the CSP framework inherently falls short of the “strategic alliance” much feared by Western analysts.

Looking across the numerous metrics included in this study, Iran appears no more dependent than the five other major states in the region examined in this study – Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Iraq, Turkey, and Pakistan. Even the language of the draft CSP is balanced with China’s other commitments in the Middle East. It bears a striking resemblance to the Chinese White Paper on the Arab world (the sole Chinese policy paper concerning Chinese-Arab relations) which was published contemporaneously with the original China-Iran CSP negotiations in 2016. The CSP with Iran is not a break from Chinese policy in the Middle East, just a continuation of the norm using standardized language.

Translation of Final Draft of Iran-China Partnership Plan

June 2020

Introduction

The People’s Republic of China and the Islamic Republic of Iran, herein referred to as “parties” to the agreement,

Represent two ancient civilizations in Asia, maintaining close partnership in a range of areas from trade and economy to politics, culture and security. Sharing numerous views and interests in bilateral ties and multilateral arenas, the two parties consider one another as important strategic partners.

By recognizing their cultural commonalities, the importance of multilateralism, the right of all nations to sovereignty, the indigenous model of development, and through sharing positions regarding different global issues, China and Iran have pushed their relationship to the strategic level on the basis of mutual interests and a win-win approach.

Given their deep-rooted and friendly diplomatic ties since 1971 and proper grounds for cooperation in such fields as energy infrastructure, science and technology, the leaderships of the two parties are strongly committed to expanding this bilateral relationship, calling for plans to boost all ties.

The present document, the two parties are confident, will open a new chapter in bilateral ties between Iran and China as two splendid civilizations of Asia, and will serve as a giant leap toward materializing the common will expressed by the leadership on both sides for deepening relations and strengthening cooperation in various fields within the framework of [China’s] Belt and Road Initiative.

This document also aims to help operationalize Article 6 of the initial joint statement issued in January 2016 on launching the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership between the People’s Republic of China and the Islamic Republic of

Iran. It does emphasize the necessity of setting up mechanisms and providing the essential infrastructure for expanding cooperation within a 25-year vision.

The two parties have agreed upon the following:

Article 1

Vision:

Through the deal, they will drive forward strategic partnership between China and Iran based on a win-win approach in bilateral, regional and global grounds.

Article 2

Mission:

Taking into account the tremendous capacities at hand for bilateral cooperation within the framework of the present document, the two parties will cooperate to achieve the following goals:

- Expansion of bilateral trade and economic ties

- Effective interaction between public and private-sector institutions as well as free and special economic zones

- Improvement of efficiency in such sectors as the economy, technology and tourism

- Strategic partnership in different economic fields

- constant and effective review of the status of the joint economic cooperation with the aim of removing hurdles and tackling challenges

- Coordination and support for one another’s positions at international bodies and regional organizations

- A strengthened enforcement of the laws in bilateral security cooperation including the fight against terrorism

- Cooperation in other fields

Article 3

Fundamental Goals:

With strategic bilateral policies, common opportunities and capacities, as well as the existing realities in mind, the two parties have enumerated and drafted the fundamental goals pursued by the present agreement in Appendix 1.

Article 4

Cooperation Grounds:

To expand comprehensive cooperation, the two parties will work together within the framework outlined in Appendix 2. Some of the key areas are as follows:

- Energy, including crude oil (production, transfer, refining and secure delivery), petrochemicals, renewable energies, civilian nuclear energy

- Highways, railroads and maritime connections with an increasing Iranian role in the Belt and Road Initiative

- High-standard banking relations, with an emphasis on the use of national currencies along with an assertive fight against money laundering and financial provision for terrorism and organized crime

- Cooperation in tourism, scientific-academic fields and technology, exchange of experience in human force training, eradication of poverty and improvement of public livelihood in underdeveloped areas

Article 5

Executive Steps:

The two parties will strengthen strategic comprehensive cooperation in all fields on the basis of joint interests and principles and within the normal frameworks of business among economic enterprises by following all the steps stated in Appendix 3 of the present document.

Article 6

Supervision and Implementation:

1. For a coordinated supervision of the implementation of the contents of the

present document, the two parties will set up a mechanism agreed upon by senior and authorized officials representing the leaderships of the two states.

2. The high-ranking representatives will hold annual meetings. Upon necessity, other relevant officials will have consultative calls with their counterparts.

3. The ministries of foreign affairs on both sides—aided by other involved institutions such as China’s Ministry of Commerce and Iran’s Ministry of Economy—will act as the body supervising the implementation of the contents of the present document and are tasked with generating work-in-progress reports and handing them to their leaderships within specified timetables.

Article 7

Cooperation in Third-Party Countries:

Given their common interests in the Belt and Road Initiative, the two parties shall encourage bilateral relations as well as multilateral ties through pursuing joint plans in neighboring or third-party countries.

Article 8

Rejection of Outside Pressure:

In line with the principle of multilateralism, the two parties shall safeguard the implementation of the Articles of the present document in the face of illegal pressure from third parties.

Article 9

Final Contents

1. Any revision of the appendices of the present document (as stated in Articles 3, 4, 5) is conditioned upon mutual consent and shall be carried out merely after coordination and mutual consultation.

2. To facilitate the implementation of the mutually-agreed-upon plans, the two parties are entitled to present suggestions, if need be, for the purposes of improvement and updated adaptability of the content of the agreement. Assurances have to be offered that such steps shall not impact or impede the implementation of ongoing projects.

3. Appendices attached to the present document shall constitute an integral part to it.

4. The present document will be in force for 25 years upon the signing date.

The present document was signed on (date) … (… (date) on the Iranian calendar) in the city of … and is available in Chinese, Persian and English copies, all of which hold equal legal validity. Should a dispute arise between the two sides, the English version shall serve as reference.

Signatures

From the Islamic Republic of Iran

From the People’s Republic of China

Click here for the full text of the paper.