Since the 1979 revolution, Iran has detained or imprisoned tens of thousands of human rights activists, including peaceful protestors, dissidents, union members, civil society organizers, feminists, students, journalists, lawyers and the unemployed. It notoriously cracked down when millions took to the streets in dozens of cities after the disputed 2009 presidential election and again during nationwide protests over economic conditions in 2017-2018 and 2019. More than 19,000 people were rounded up during those three demonstrations. But many others have been arrested at smaller protests since 1999.

The judiciary, headed by a cleric and dominated by conservatives and revolutionary “principlists,” has invoked a broad and often vague range of charges against activists, such as “colluding against national security” or “distributing propaganda against the state.” Female activists who have challenged the Islamic Republic’s restrictive social laws have been imprisoned for crimes such as “promoting prostitution” or “insulting Islam.”

Iran has faced widespread criticism from foreign government and human rights groups for more than 40 years. The Islamic Republic has “heavily suppressed the rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly” for dissidents challenging the theocracy, Amnesty International reported in 2019. The state’s restrictions on speech, its harsh sentences, and its monitoring of internet communications and social media are “among several factors that deter citizens from engaging in open and free private discussion,” the 2020 Freedom House report said. Iranian state television has a long record of airing “confessions extracted from political prisoners under duress, and it routinely carries reports aimed at discrediting dissidents and opposition activists.”

The State Department’s 2019 Human Rights report charged that Iran’s judiciary often “appeared to have determined the verdicts in advance, and defendants did not have the opportunity to confront their accusers or meet with lawyers. For journalists and defendants charged with crimes against national security, the law restricts the choice of attorneys to a government-approved list.”

Related Material: “Profiles: Iran’s Jailed Human Rights Lawyers”

Prison conditions are “harsh and life threatening,” the State Department added. Inmates often face physical and/or psychological torture. Prisoners given multiple sentences are eligible for release after serving the longest sentence, but the judiciary has in some cases tacked on additional charges as a prisoner nears release. In prison, some activists have continued to advocate for human rights in open letters and social media posts relayed through relatives, which has led to retaliatory measures by the state on prisoners or their families.

The following are profiles of prominent human rights activists imprisoned between 2004 and 2020. The first three—Narges Mohammadi, Mahmoud Beheshti Langroudi, and Mohammad Habibi—are among the most prominent recent activists; they were released in 2020. The others are profiled alphabetically.

Narges Mohammadi

Narges Mohammadi, who was born in 1972 in Zanjan, led two prominent human rights groups. She served as President of the National Council of Peace in Iran and Vice President of the Defenders of Human Rights Centre (DHRC), a group founded by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Shirin Ebadi. She advocated for women’s rights, challenged the death penalty and chronicled prisoner abuse, including her own time in jail. Mohammadi has been arrested five times and spent more than eight years in prison. She was released on October 7, 2020 after the court commuted her last sentence.

Mohammadi was detained twice in the 1990s after she founded the Illuminating Student Group of young dissidents at Imam Khomeini University. Later, as an engineer and journalist, she wrote critical essays about the regime’s restrictions on women’s rights; she joined the DHRC in 2003.

Mohammadi was detained twice in the 1990s after she founded the Illuminating Student Group of young dissidents at Imam Khomeini University. Later, as an engineer and journalist, she wrote critical essays about the regime’s restrictions on women’s rights; she joined the DHRC in 2003.

In 2009, the government arrested Mohammadi for membership in the DHRC. She was released on bail but the court banned her from travel abroad; she was also fired from her engineering job. In 2010, she was detained again and spent a month in solitary confinement until she was released for medical treatment of a neurological disorder. In October 2011, she was charged with “colluding against national security, generating propaganda against the state, and being part of the DHCR.” She was sentenced to 11 years, later reduced to six years. While in prison, her husband and two children fled to France. Her health worsened; she was released on bail for medical treatment in 2013.

In October 2014, Mohammadi lambasted the government for prisoner abuse and political hypocrisy in a speech honoring dissident journalist Sattar Beheshti, who had died in prison in 2012. “How is it that members of parliament suggest a plan for ‘the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice,’ but nobody spoke up two years ago when an innocent human being named Sattar Beheshti died after being tortured by his interrogator?” she asked. A video of the speech went viral.

In May 2015, she was arrested and charged with “gathering and colluding with intent to harm national security,” “spreading propaganda against the system” and “founding and running an illegal organization.” While in prison, she was sentenced to 16 years, later reduced to 10 years. Her health continued to deteriorate, and in August 2018 she was temporarily transferred from Evin Prison to the Imam Khomeini Hospital.

In prison, Mohammadi staged multiple protests over conditions, especially the lack of medical care. In January 2019, she went on a hunger strike over the “illegal, inhumane and unlawful” treatment of prisoners. She led a second hunger strike in December in sympathy with nationwide protests over economic conditions. She was transferred to Zanjan Women’s Prison as punishment. In an open letter in September 2020, Mohammadi described prison abuse as a “clear message that [the regime] knows no legal, logical or religious bounds in denying the rights of dissidents who will suffer ever more until they die, break or repent.”

Mohammadi on women prisoners in an interview with Iran Wire in October 2020: “These women are just victims. In the murders they committed, or in any other crimes, everyone had plainly been a victim. They were victims of an authoritarian regime; victims of a patriarchal, misogynistic society and government. Now, the victims of these conditions were also victims in prison, and now they had lost everything.”

Mohammadi was denied contact with her family from September 2019 until July 2020. In July, her two teenage children tweeted a video begging the international community to “be the voice of their mother” and hold the Iranian regime accountable for prisoner abuse.

Mahmoud Beheshti Langroundi

Mahmoud Beheshti Langroudi, who was born in 1960 in Langarud, is a teachers’ rights activist and former spokesman for the Iranian Teachers’ Trade Association. A veteran of the Iran-Iraq war, he was detained four times and sentenced to 14 years, five of which he served. He was released in June 2020 after completing the longest of multiple sentences.

Mahmoud Beheshti Langroudi, who was born in 1960 in Langarud, is a teachers’ rights activist and former spokesman for the Iranian Teachers’ Trade Association. A veteran of the Iran-Iraq war, he was detained four times and sentenced to 14 years, five of which he served. He was released in June 2020 after completing the longest of multiple sentences.

Beheshti Langroudi, dubbed the Teachers’ Activist, was first picked up by security forces in July 2004. He was charged with “activities against national security” for organizing teachers’ union activities; he was found not guilty Between 2007 and 2015, he was arrested and sentenced three times without actually being summoned to prison: In March 2007, he was arrested after a teachers’ rally and sentenced to four years, but was soon released on bail. The sentence was suspended. He was arrested in April 2010 for protesting but was, again, released on bail. He was not tried until 2013, when he was charged with “colluding against national security” and “propaganda against the state.” The trial reportedly lasted less than eight minutes. He was sentenced to five years but not imprisoned. Finally, in September 2015, he was arrested and sentenced to another five years, bringing his total sentence to 14 years. He began serving the sentences that month.

Langroudi in a letter from prison announcing a hunger strike on July 12, 2018: “Given that I have no legal options to dispute my convictions or seek a review… I will refuse to eat or drink anything other than water, tea, sugar and salt until further notice.”

In November 2015, Beheshti Langroudi began a 20-day hunger strike; he was temporarily released in December. He was forced to return to prison a month later. In April 2016, he staged another hunger strike; he was conditionally released after 22 days. He was ordered back to prison in October 2016, although he was not forced to return until September 2017. He staged a third hunger strike in July 2018. He was furloughed in March 2020 during the coronavirus pandemic, but returned to prison in May. In June 2020, he was released; he remained free as of November 2020.

Mohammad Habibi

Mohammad Habibi, who was born in 1989, is a teacher who served on the board of directors of the Teacher’s Trade Union of Iran. He was first detained in March 2018 and spent more than two years in prison before being released in November 2020.

Mohammad Habibi, who was born in 1989, is a teacher who served on the board of directors of the Teacher’s Trade Union of Iran. He was first detained in March 2018 and spent more than two years in prison before being released in November 2020.

In May 2018, he was arrested at a teachers’ demonstration and charged with “collusion against national security,” “propaganda against the regime” and “disrupting public order.” He was sentenced to 10.5 years and was reportedly denied medical care. In April 2020, the court forbade Habibi from teaching for two years after his sentence ended. He was eligible for early parole in October 2020 after serving a third of his term, but he was denied release until November 2020, when he was freed after serving 30 months.

Habibi and Farhad Meysami in an open letter on Oct 8, 2019: “We consider this new wave of pressure and blatant violation of prisoners' rights as the new policy of the upstream decision-makers, and as citizens with human and legal rights, we explicitly declare to you that: Other current laws in the country regarding the rights of prisoners and the non-response of the head of the prison to the repeated requests of prisoners to discuss this matter, we no longer consider ourselves obliged to comply with the arbitrary laws of your prisons.”

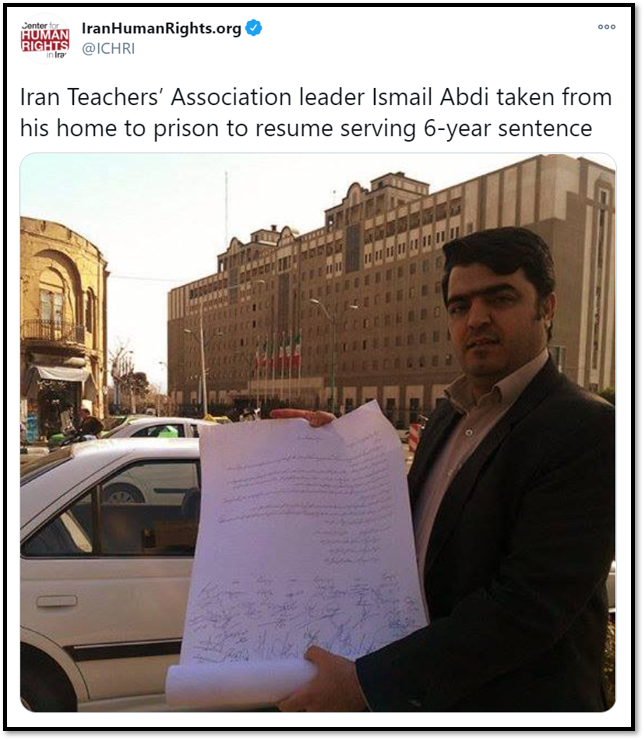

Ismael Abdi

Ismael Abdi, a teacher who was born in 1974, has campaigned for teachers’ rights and free education since at least 2007. He was Secretary General of Iran’s Teachers’ Trade Association from 2013 to 2016. He was detained five times and spent more than four years in prison between 2015 and 2020.

Ismael Abdi, a teacher who was born in 1974, has campaigned for teachers’ rights and free education since at least 2007. He was Secretary General of Iran’s Teachers’ Trade Association from 2013 to 2016. He was detained five times and spent more than four years in prison between 2015 and 2020.

Abdi was detained several times between March 2007 and May 2010 for attending protests and lobbying on behalf of the teachers’ union. He was usually held for a few weeks but not charged. In June 2015, he was arrested after he applied for a visa to attend a teacher’s conference in Canada. He was charged with “propaganda against the regime” and “gathering and collusion to act against national security.” In February 2016, he was sentenced to six years.

Langroudi and Abdi in an open letter on Oct. 4, 2018: “Iranian teachers are trying to prevent the development of education monetization. They want to provide free and quality education for all children, but the government, with its policy of privatizing education and attacking the low-income table, is increasing the number of working children and girls leaving school.”

Abdi went on a hunger strike on International Worker’s Day in May 2016 to protest the suppression of unions. He was released on bail after 16 days, but in November 2016 he was ordered to serve the rest of his sentence. He staged a second hunger strike from April until June 2017 over union rights. He contracted coronavirus in August 2020, but received limited medical treatment. He remained in prison as of November 2020.

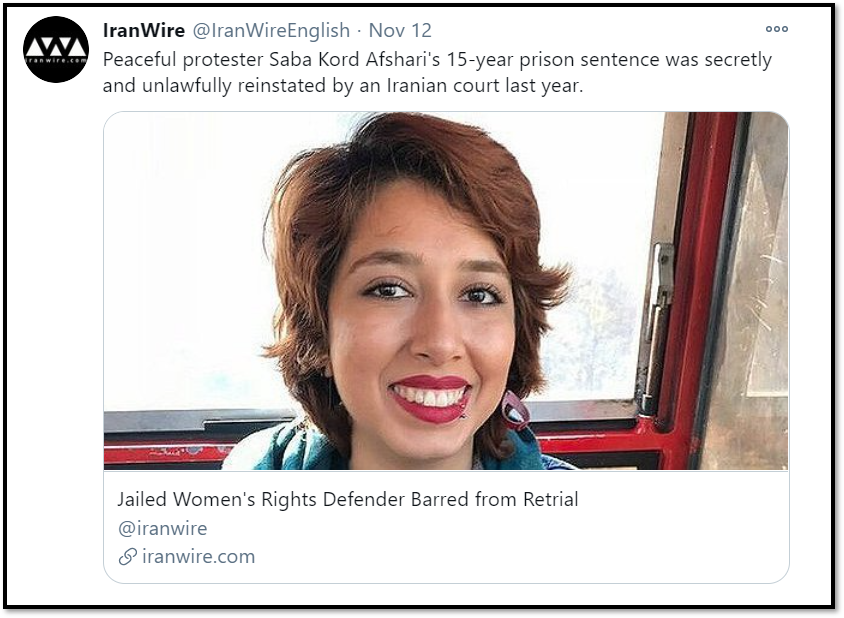

Saba Kord Afshari

Saba Kord Afshari, born in 1998, is a women’s rights activist who campaigned against mandatory hijab laws. She has been arrested twice and spent more than two years in prison.

Saba Kord Afshari, born in 1998, is a women’s rights activist who campaigned against mandatory hijab laws. She has been arrested twice and spent more than two years in prison.

In August 2018, she was arrested at a rally protesting government corruption, charged with “disruption of public order” and sentenced to one year. She was released in February 2019. In June 2019, Afshari posted a video of herself without the headscarf during the White Wednesdays protests. She was arrested for “encouraging people to commit immorality and/or prostitution” and sentenced to a total of 24 years in prison. Security officials detained her mother to pressure Afshari into confessing to the crime on state television. Her request for a retrial was rejected in November 2020 and she remained in Evin as of November 2020.

Kord Afshari in remarks after her first release in February 2019: “When I saw the situation of prisons closely, especially in Qarchak, I came to the conclusion that we in Iran only have the name of human rights. In fact, in Iran, there are no rights for humans, let alone respecting human rights in the prisons.”

Yasman Aryani

Yasman Aryani, who was born in the mid-1990s in Karaj, is a women’s rights activist who challenged mandatory hijab laws. She has been detained twice and has spent nearly two years in prison.

Aryani was first arrested in August 2018 at protests against government corruption. She served six months of a one-year sentence for “disrupting public order” before being pardoned in February 2019. In March 2019, on International Women’s Day, Aryani, her mother Monireh Arabshahi, and Mojgan Keshavaraz handed out flowers to riders on a female-only car on the Tehran Metro to encourage resistance to compulsory hijab laws. A video of the protest went viral.

Aryani, Kord Asfhari and Atena Daemi in an open letter on Oct. 17, 2019: “In all these years, the misogynist government has fought women and mothers who stand up for freedom and justice. That the fight continues is itself a sign of increasing awareness and acceleration of women’s struggles and protests.”

Aryani and her mother were detained at their home in April 2019 and charged with “assembly and collusion to act against national security,” “propaganda against the state,” “encouraging and providing for [moral] corruption and prostitution.” They were sentenced to 16 years. Aryani’s sentence was later reduced to nine years and seven months. She and her mother were transferred from Evin to Rajaee Shahr Prison in October 2020.

Jafar Azimzadeh

Jafar Azimzadeh, who was born in 1966, is a prominent labor activist and the Chairman of the Free Workers Union of Iran. He has been detained three times and spent more than four years in prison for organizing unions and strikes, demanding unpaid wages, and speaking to foreign media.

Jafar Azimzadeh, who was born in 1966, is a prominent labor activist and the Chairman of the Free Workers Union of Iran. He has been detained three times and spent more than four years in prison for organizing unions and strikes, demanding unpaid wages, and speaking to foreign media.

Azimzadeh was first detained on May 1, 2009, and again on May 1, 2014, for protesting on International Worker’s Day. He was held for a few weeks both times. In March 2015, he was tried for “assembly and collusion against national security” and “propaganda against the state.” He was sentenced to five years. He was imprisoned from November 2015 until June 2016, when he was temporarily released on bail after a two-month hunger strike. In September 2016, Azimzadeh and a colleague were re-tried for the same charges; they were sentenced to an additional 11 years. He was ordered to return to prison in December 2016 and served six months; he was temporarily released when the court acquitted him of one charge in June 2017.

Azimzadeh in an interview with the Center for Human Rights in Iran in October 2016: “All the charges and accusations against me are for trade union activities, such as organizing unions, non-violent labor strikes, and interviews with the media to defend workers’ rights, myself included. I am a worker.”

In January 2018, Azimzadeh was ordered to serve the rest of his sentence. He was eligible for pardon in February 2020, but he was sentenced to another one year and one month for signing a statement that protested prison medical policy. He contracted coronavirus in August 2020 and was hospitalized. He was returned to a public ward in September 2020.

Atena Daemi

Atena Daemi, who was born in 1988, is a children’s rights activist and an outspoken critic of the death penalty. She was first arrested in 2014 for meeting the families of prisoners, handing out flyers against the death penalty, and denouncing the regime on Facebook. She was imprisoned in 2016; her family claimed that she was prosecuted seven times while serving her sentence.

Atena Daemi, who was born in 1988, is a children’s rights activist and an outspoken critic of the death penalty. She was first arrested in 2014 for meeting the families of prisoners, handing out flyers against the death penalty, and denouncing the regime on Facebook. She was imprisoned in 2016; her family claimed that she was prosecuted seven times while serving her sentence.

Daemi was detained in October 2014 and held in solitary confinement. She was later charged with “assembly and collusion against national security,” “insulting the supreme leader” and “concealing criminal evidence.” In June 2015, she was sentenced to 14 years; the sentence was later reduced to seven years. She was temporarily released on bail in February 2016, but returned to prison in November 2016. She subsequently developed severe health problems, including skin disease, stomach problems and deteriorating eyesight.

In April 2017, Daemi went on hunger strike to protest the arrest of her two sisters, who after Daemi complained to the court that the Revolutionary Guards used excessive force during her arrest. Daemi’s health deteriorated during her hunger strike, but prison authorities reportedly refused her medical care.

Daemi in an open letter from prison on June 6, 2019: “They want to suffocate the voice concealed in my pen. But having learned that political prisoners in my country have defied such foolish jokes over the past two decades, like my friends, I keep learning from them to reach what I have been imprisoned for. The more pressure they impose, the closer their demise!!”

In September 2019, authorities added three years and eight months to her sentence for “disseminating propaganda” after she wrote an open letter criticizing executions and for “insulting the Supreme leader” when she sang in honor of executed prisoners. In December 2019, Daemi and other female prisoners, including Narges Mohammadi, led a sit-in to protest the regime’s crackdown on nationwide protests. Daemi was temporarily put in solitary confinement. After she joined a prison protest in February 2020, the court again extended her sentence by two years and added 74 lashes. She remained in Evin as of November 2020.

Sepideh Gholian

Sepideh Gholian, who was born in 1995 in Dezful, is a journalist and labor rights activist. She has been arrested twice since 2018. In 2019, she wrote a book called “Tilapia Sucks the Blood of Hur al-Azim” which described torture and inhumane conditions in Sepidar Prison.

Sepideh Gholian, who was born in 1995 in Dezful, is a journalist and labor rights activist. She has been arrested twice since 2018. In 2019, she wrote a book called “Tilapia Sucks the Blood of Hur al-Azim” which described torture and inhumane conditions in Sepidar Prison.

Gholian was first detained in November 2018 for reporting on a protest organized by the labor union of the Haft Tappeh sugar factory. She was released on bail in December, but arrested with her brother in January 2019 after she tweeted about the interrogations and abuse she suffered in detention. The Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) aired her forced confession to incriminate her.

In September 2019, Gholian was charged with “assembly and collusion to act against national security,” “membership in an illegal group of Gam,” “propaganda against the state,” and “publishing false news.” She was sentenced to 19 years and six months; the court later reduced her sentence to five years. She staged a five-day hunger strike in October; she was temporary released on bail. Gholian wrote a memoir while on furlough, which was published by IranWire in 2020. It described the state’s practice of forcing confessions and discrimination against female prisoners.

Gholian in Tilapia Sucks the Blood of Hur al-Azim, a book about her imprisonment in 2018: “I feel I have been sucked into an endless black hole and trapped there. It is a very small cell, maybe 5 square meters, with a filthy brown carpet and two filthier blankets.”

She was arrested a second time for participating in the November 2019 protests against oil price hikes. She subsequently sued the IRIB for defamation and disinformation. The IRIB retaliated with a counter-suit. Gholian was released on bail in the spring of 2020 during the coronavirus pandemic. In June 2020, she was reportedly offered a pardon if she apologized to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, but she refused. She was forced to return to prison, where she remained as of November 2020.

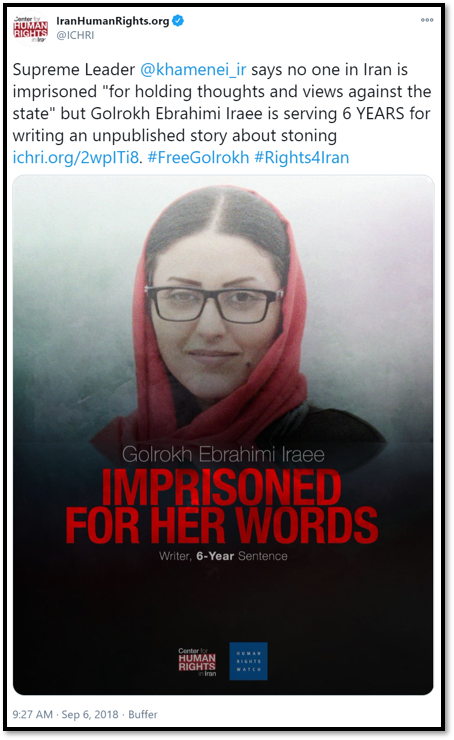

Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee

Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee, who was born in the early 1980s, is an accountant married to Arash Sadeghi, a fellow activist. She was imprisoned for merely writing a story, which was never published, that criticized the law on stoning adulterers to death. She has been arrested twice and spent three and a half years in prison.

Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee, who was born in the early 1980s, is an accountant married to Arash Sadeghi, a fellow activist. She was imprisoned for merely writing a story, which was never published, that criticized the law on stoning adulterers to death. She has been arrested twice and spent three and a half years in prison.

Intelligence officials reportedly found the handwritten text of her unpublished story when they raided her home in September 2014. She was charged with “insulting Islam,” “conspiracy against national security” and “propaganda against the regime” and sentenced to seven years. She was temporarily released in January 2017 after her husband went on hunger strike to protest her arrest, but she was forced to return to prison less than a month later.

Iraee and Daemi in a letter to foreign ambassadors who toured Evin Prison published on July 8, 2017: “We are in prison because we wanted to present the true picture of the deplorable human rights situation in the Islamic Republic of Iran. We have paid a heavy price for this and our families have also been intimated in various ways. We have even been kept hidden from you.”

Iraee and Atena Daemi, another women’s rights activist, protested in public letters and hunger strikes. The first letter and strike, in July 2017, cited poor conditions and inadequate medical care in Evin. The two women went on hunger strike again in February 2018 to protest their illegal transfer from Evin to Shahr-e Ray Prison, a former industrial chicken farm in Varamin. They also criticized the death penalty in open letters and by singing in prison. In September 2019, Iraee and Daemi were charged with “insulting the supreme leader" and "promoting propaganda against the state” and sentenced to an additional two years and one month. Iraee remained in prison as of November 2020.

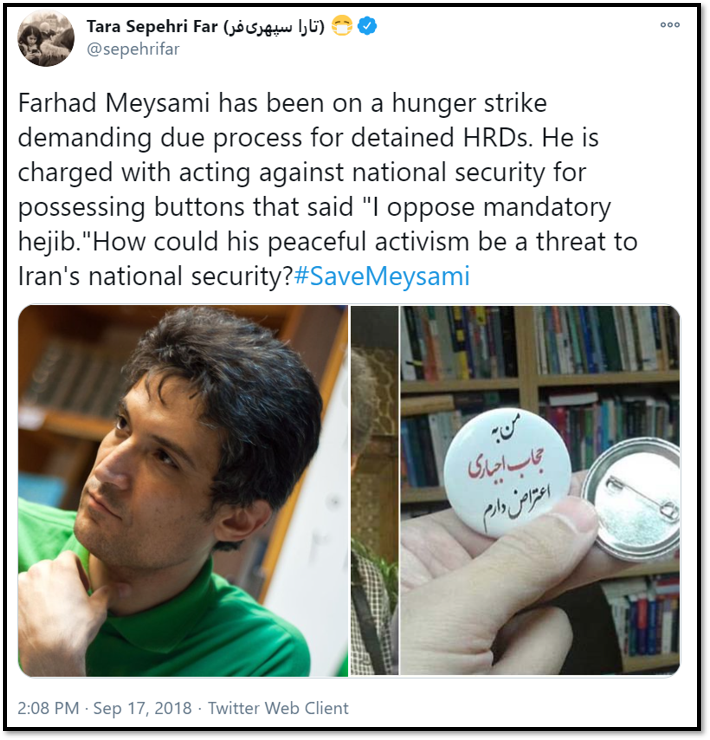

Farhad Merysami

Farhad Meysami, born in 1969, is a medical doctor and women’s rights activist who campaigned against laws requiring women to wear hijab to cover their hair. Meysami was arrested in July 2018 after security agents found books on human rights and buttons declaring “I protest forced hijab” in his office.

Farhad Meysami, born in 1969, is a medical doctor and women’s rights activist who campaigned against laws requiring women to wear hijab to cover their hair. Meysami was arrested in July 2018 after security agents found books on human rights and buttons declaring “I protest forced hijab” in his office.

Meysami was charged with “assembly and collusion against national security,” “promoting prostitution” and “propaganda against the state.” In January 2019, he was sentenced to six years; he was reportedly denied legal counsel during his trial.

He continued to protest injustice from prison. On August 1, 2018, he began a hunger strike that lasted 145 days to protest the arrest of fellow activist Reza Khandan.

In a message published on Facebook by fellow activist Reza Khandan on Aug. 24, 2018: “My hunger strike is out of respect for my own dignity and the dignity of those who have been detained on baseless accusations; those who are being interrogated while they have no access to a proper and legitimate legal representation. I will not, under any conditions, succumb to the demands of this illegal procedure.”

In October 2019, Meysami and Mohammad Habibi, his cellmate, wrote an open letter detailing prisoner abuse. He was moved to Rajaee Shahr Prison in Karaj a month later. He contracted the coronavirus in October 2020; he was isolated for eight days but then returned to a public ward.

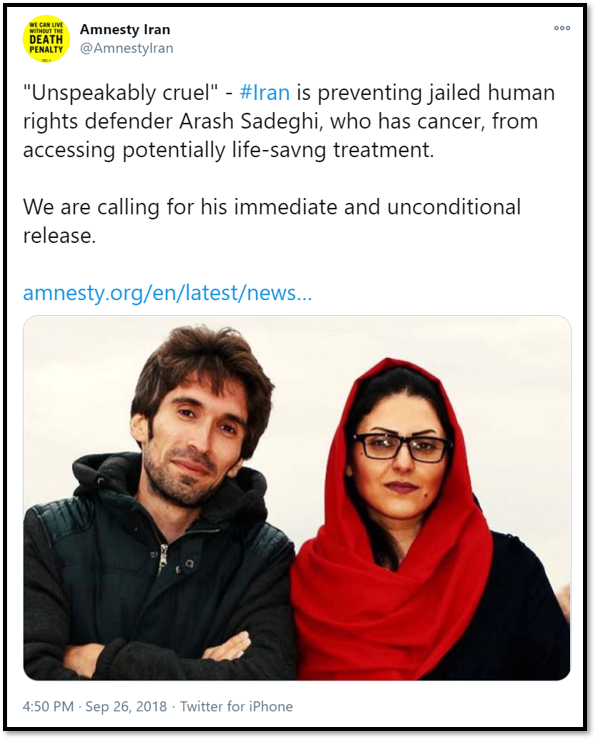

Arash Sadeghi

Arash Sadeghi, who was born in 1986, campaigned for former prime minister Mir Hossein Mousavi during the 2009 presidential election. He has been detained six times for protesting unfair elections and sharing information with international human rights groups. He has spent eight years in prison, during which he was denied treatment for bone cancer.

Arash Sadeghi, who was born in 1986, campaigned for former prime minister Mir Hossein Mousavi during the 2009 presidential election. He has been detained six times for protesting unfair elections and sharing information with international human rights groups. He has spent eight years in prison, during which he was denied treatment for bone cancer.

Sadeghi was first detained in July 2009 at protests over alleged electoral fraud, but was released without formal charges. His mother reportedly suffered a heart attack during a security raid on their home in November 2009; she died four days later. He was detained again without being charged in December 2009. In 2010, Sadeghi was charged with “assembly and collusion against national security” and “propaganda against the state.” He was sentenced to six years, later reduced to one year. He was released in 2011, but detained again in January 2012 and held without charge until October 2013.

Sadeghi was detained in September 2014 and held for seven months. In December 2015, he was arrested and charged with “conspiracy against national security,” “propaganda against the regime,” and “insulting the founder of the Islamic Republic.” He was sentenced to 19 years.

Sadeghi’s wife, Golrokh Ebrahimi Iraee, is also an activist. She was arrested in 2016 for writing about the stoning of a young woman for adultery. Sadeghi went on a71-day hunger strike until Iraee was released.

Sadeghi in an open letter from August 2018: “If Western officials are serious about this commitment, they cannot rightly plead economic and trade interests as an excuse to turn a blind eye to operatives of this overseas assassination campaign, the very same people who eliminate dissidents within Iran’s borders. Any kind of silence or cooperation with the Islamic Republic enables domestic oppression and threatens the opposition abroad.”

In 2018, Sadeghi developed bone cancer. He was temporarily released for surgery in September 2018, but was reportedly denied post-surgical care. Sadeghi remained in Evin as of November 2020.

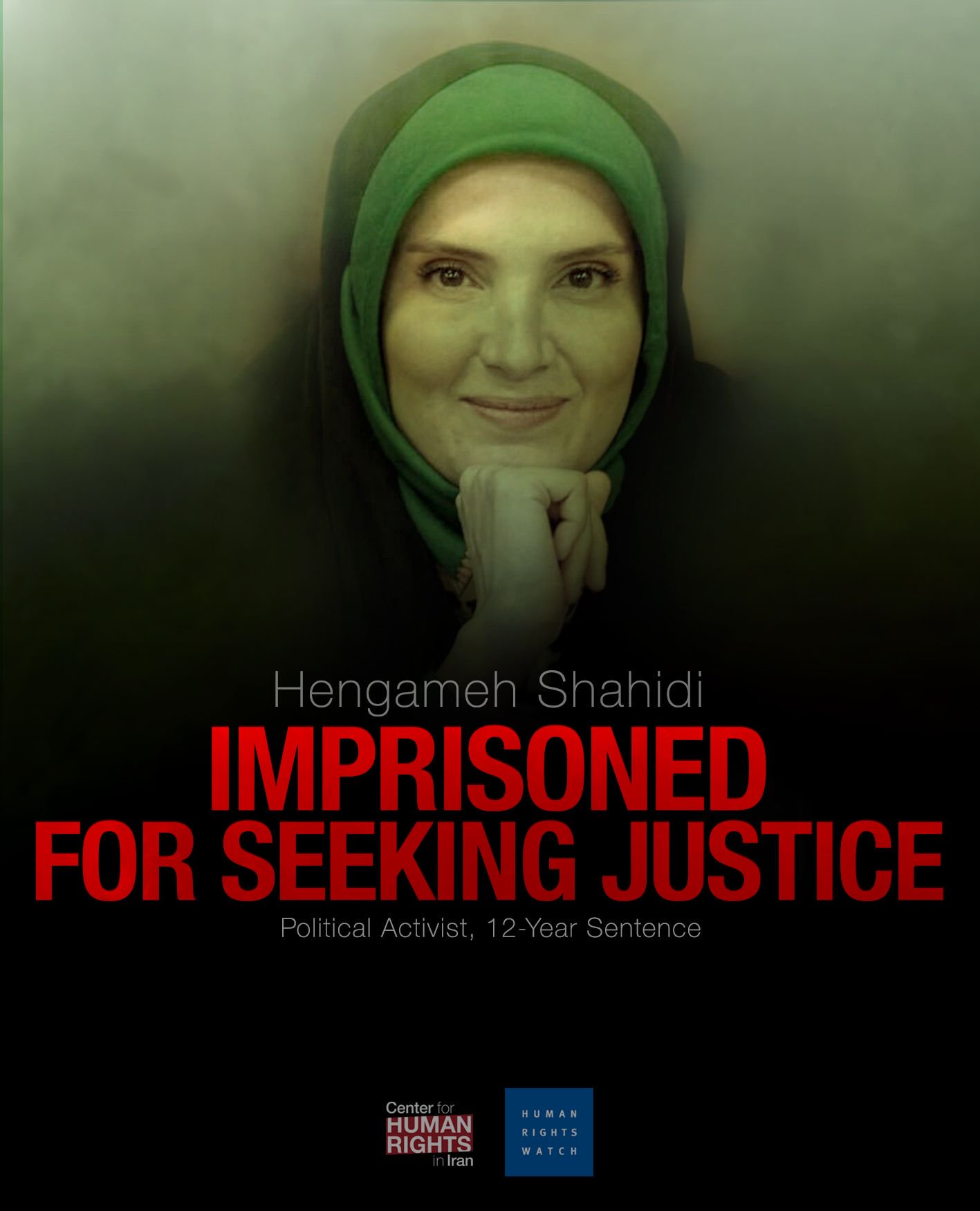

Hengameh Shahidi

Hengameh Shahidi, who was born in 1975, is a journalist who advised presidential candidate and former speaker of parliament Mehdi Karroubi in the 2009 election. She joined the 2009 Green Movement opposition after the election; she was prosecuted for protesting, speaking with media, supporting women’s rights, and campaigning against stoning for adultery. She has been detained three times and spent more than four years in prison.

Shahidi was first detained in July 2009 during the Green Movement protests over presidential election results. She was held in Evin for four months; she went on hunger strike until she was released on bail in November 2009. She was subsequently charged with “gathering and colluding with intent to harm state security” and “propaganda against the system;” she was sentenced to six years. She reportedly suffered health problems—including rheumatic heart disease, severe depression, and kidney and stomach problems—but she was allowed limited medical care. In May 2011, she was released on medical grounds.

Shahidi was first detained in July 2009 during the Green Movement protests over presidential election results. She was held in Evin for four months; she went on hunger strike until she was released on bail in November 2009. She was subsequently charged with “gathering and colluding with intent to harm state security” and “propaganda against the system;” she was sentenced to six years. She reportedly suffered health problems—including rheumatic heart disease, severe depression, and kidney and stomach problems—but she was allowed limited medical care. In May 2011, she was released on medical grounds.

Shahidi was detained without charge again in March 2017 before the presidential election in May. While in solitary confinement, she staged another hunger strike; she was hospitalized after two months for a heart condition. She was released in August 2017.

Shahidi was arrested again in June 2018 for criticizing the judicial system. In December, she was charged with “defamation,” “dissemination of false information,” “insulting regime officials,” “propaganda against the regime” and “conspiracy against national security.” She was sentenced to 12 years and nine months. She was only allowed two visits with her family and lawyer in six months, and her appeal was denied.

Shahidi in a letter posted on Instagram in March 2017: “You [President Hassan Rouhani] were supposed to be a breath of fresh air for reformists after the oppressive years under [President Mahmoud] Ahmadinejad, and not choke the air out of them to become president like he did.”

In March 2020, Shahidi was reportedly infected with coronavirus. She was furloughed to receive medical attention in April, but in June 2020 was reported to be back to prison.

Caitlin Crahan was a research assistant at the Woodrow Wilson Center.