By Kelsey Davenport

Since July 1, Iran has engaged in two breaches of the 2015 nuclear deal. On July 1, it increased its stockpile of low-enriched uranium above the 300-kilogram limit. On July 8, it increased enrichment from the limit of 3.67 percent to 4.5 percent. Iran had previously complied with the agreement, even after President Trump abandoned it in May 2018. What do Iran’s decisions mean for the future of the JCPOA (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action)?

Iran’s decision to breach the 300-kilogram limit on low-enriched uranium does not pose a significant proliferation threat, but it does increase the risk that the JCPOA will collapse. Iran’s action was driven by the Trump administration’s reimposition of sanctions in May 2018 and its systematic campaign to deny Iran any benefits from complying with the deal. European parties to the deal said their support for the accord is contingent on Iran’s continued compliance. Failure to resolve the breach could trigger an escalatory cycle of actions by the United States, Iran or other parties to the deal—and ultimately kill the JCPOA.

Iran’s breaches of the JCPOA will not necessarily lead to the deal’s demise. Iran said it will resume compliance and refrain from further violations if the Europeans deliver on sanctions relief, namely by establishing banking channels and a mechanism to facilitate oil transactions. At a June 28 meeting of the Joint Commission, the body set up by the JCPOA to oversee its implementation, Britain, France, Germany announced progress on a “special purpose vehicle”— known as INSTEX — to bypass U.S. sanctions and facilitate trade with Iran. They also announced creation of an experts group to explore options for Iran to transfer out low-enriched uranium to keep its stockpile below the cap.

Tehran cited U.S. sanctions that prevent Iran from exporting its low-enriched uranium as justification for breaching the deal. Tehran argued that the U.S. measures, announced in May 2019, impede its ability to honor its obligations — even though Iran could also blend down its enriched uranium (or dilute it to natural levels) to stay below the 300-kilogram limit.

It is not clear yet if the recent efforts by Europe, China, and Russia to deliver the sanctions relief Iran was promised under the 2015 deal will be sufficient to persuade Iran to return to compliance. If not, the two breaches in early July may be the first steps down a slippery slope of deal violations that ultimately pushes the remaining parties to respond or withdraw from the accord.

How does it change Iran’s ability to produce enough fuel for a nuclear bomb—and the time required to do it? What additional steps would it need to take to produce a deployable weapon?

The JCPOA limited Iran to enriching uranium to 3.67 percent (a level suitable for fueling nuclear power reactors) and to stockpiling no more than 300 kilograms of uranium gas enriched to that level. A slight excess in 3.67 percent enriched uranium, or uranium enriched to 4.5 percent does not, by itself, pose a near-term proliferation risk and will not have an immediate impact on Iran’s so-called breakout time (the time it would take to produce enough fissile material for a nuclear weapon). Prior to the JCPOA, the timeframe was about 2-3 months. Under the JCPOA, it was about 12 months.

If Iran were to pursue a nuclear weapon, it would have to produce at least 1,050 kilograms of 3.67 percent enriched uranium—almost four times its currently stockpile— and then enrich it to weapons-grade levels, which is more than 90 percent enriched uranium. Once Iran produced enough fissile material for a bomb (around 25 kilograms of uranium enriched to 90 percent) it would need to convert the gas into powder and then fabricate it into a metallic form to create the fissile core of a nuclear warhead. The fabricated uranium would then be fitted with an explosives package and integrated into a delivery system, likely a ballistic missile. All of these steps take time, and the more intrusive monitoring and verification mechanisms put in place by the deal — and still in place — would provide early warnings if Tehran decided to pursue a nuclear bomb.

How hard would it be for Iran to reverse the processes started? How long would it take?

Iran can quickly reverse the steps it has taken to date by blending down or diluting the enriched uranium over the 300-kilogram limit. Blending down low-enriched uranium returns it to natural-level concentrations of U-235, which are typically about 0.7 percent. This is a process Iran has used in the past to dilute enriched uranium. The deal does not set a limit on Iran’s stockpile of natural uranium, so the size of that stockpile would not affect Iran’s compliance with its commitments. Iran could likely complete this process in days or weeks.

Why did Tehran breach the stockpile and enrichment limits?

Iran’s decisions to breach the 300-kilogram limit on low-enriched uranium and enrich above 3.67 percent are not a dash to a nuclear bomb. They do not mean that Tehran has made the decision to pursue nuclear weapons. Breaching these limits does not pose a near-term proliferation risk. Given the transactional nature of the JCPOA—it trades sanctions relief for stringent restrictions and monitoring of nuclear activities—it is unsurprising that Iran decided to retaliate after the Trump administration re-imposed sanctions, despite acknowledging Iran was meeting its JCPOA commitments.

The two moves appear to be a carefully calibrated political response to demonstrate Iran’s impatience with European, Russian, and Chinese efforts to compensate for U.S. sanctions. The actions are an attempt to create leverage to push them to redouble efforts. President Hassan Rouhani said Iran will reverse its actions if they deliver on sanctions relief.

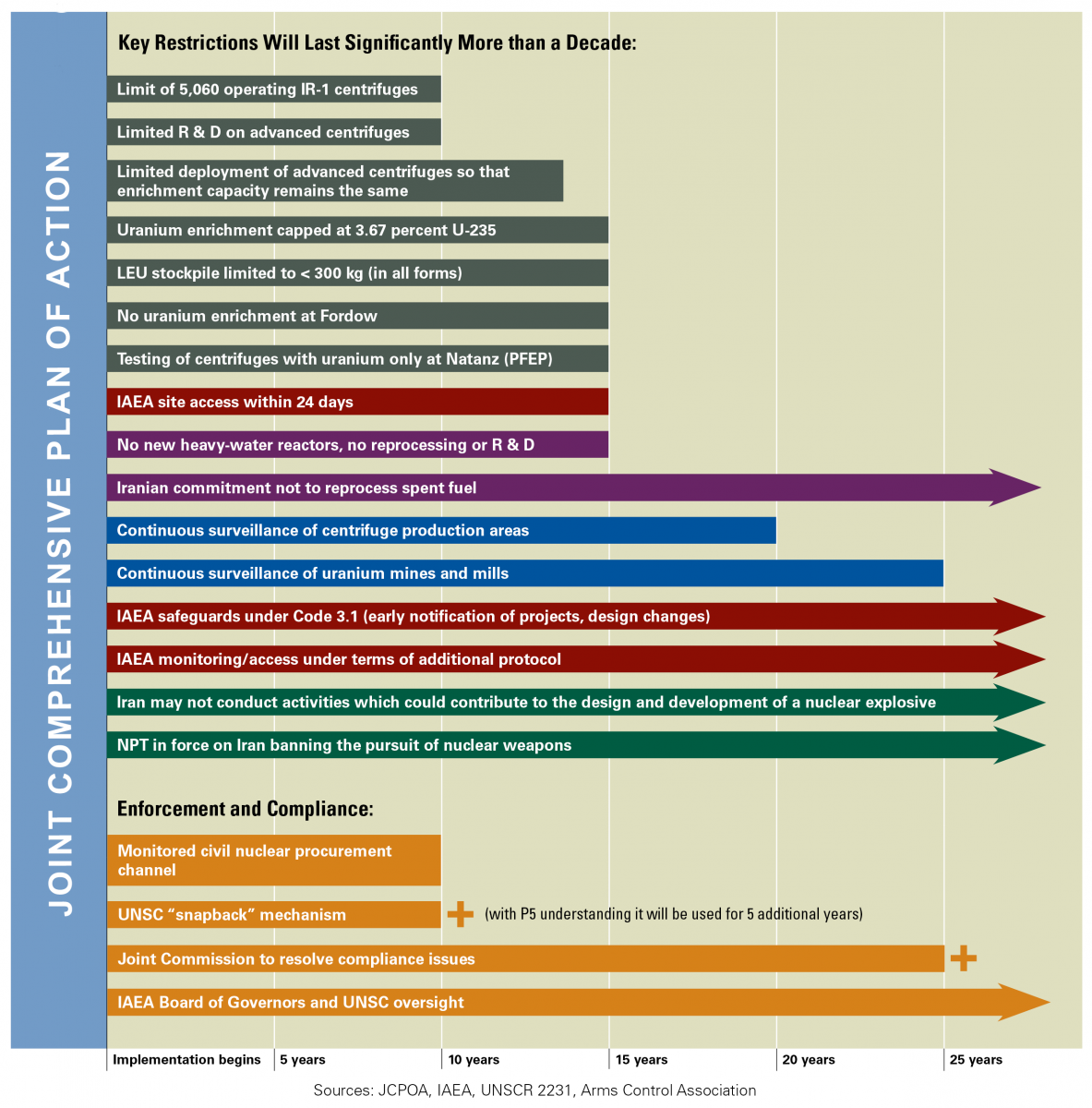

What are the key restrictions under the JCPOA?

How have the five other major powers who brokered the deal reacted?

The remaining parties to the JCPOA (Britain, China, France, Germany and Russia) urged Tehran to return to compliance. Britain, France and Germany, along with the E.U. High Representative, said that they were “considering next steps” under the terms of the JCPOA.” The JCPOA contains a dispute resolution mechanism that can be used by any party to address issues of compliance. Russia and China, however, blamed Iran’s action on U.S. sanctions. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov specifically cited U.S. sanctions for preventing Iran from being able to ship out its low-enriched uranium—and remain below the 300-kilogram limit. Any country or company that helps ship out Iran’s uranium faces U.S. sanctions.

The Europeans issued sterner reactions to Iran’s decision to enrich uranium above 3.67 percent. “Iran has broken the terms of the JCPOA,” said a British Foreign Office spokesman. “While the U.K. remains fully committed to the deal, Iran must immediately stop and reverse all activities inconsistent with its obligations.” Germany said it was “extremely concerned” and would await further information from the U.N. nuclear watchdog, the International Atomic Energy Agency. “We strongly urge Iran to stop and reverse all activities inconsistent with its commitments under the JCPOA,” said Germany’s Federal Foreign Office in a statement.

What are the prospects that the Europeans, China or Russia will seek to invoke “snapback sanctions” – as allowed by the JCPOA – at the United Nations?

At this point, the remaining parties are unlikely to go to the Security Council to ask for “snapback” sanctions. Re-imposing U.N. sanctions could effectively kill the JCPOA, as it would remove incentives for Iran’s compliance. It would formally obligate all U.N. member states to enforce Security Council sanctions on Iran and require Iran to cease nuclear activities permitted under the JCPOA, including uranium enrichment for its energy reactors. Given the extreme consequences of this step, the Europeans, Russia and China are likely to utilize all the options within the JCPOA to resolve the compliance dispute first. If the JCPOA’s resolution mechanisms fail to get Iran to comply, the states may first pursue other options to penalize Iran short of snapping back U.N. sanctions. But that calculus could change if Iran takes further steps to breach the deal or is unwilling to resolve the current breach.

On June 25, the secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, Ali Shamkhani, warned that Iran might stop complying with other parts of the JCPOA unless the Europeans provide relief to its oil and banking sectors from U.S. sanctions. What other steps is Tehran considering?

Iran’s next move could be to enrich up to 20 percent. Until 2013, Iran was enriching uranium to 20 percent to fabricate fuel for its research reactor. But it halted that activity and eliminated its stockpile of material as part of the interim nuclear deal. Iran could justify its decision to pursue uranium enriched to 20 percent as necessary to produce fuel for the Tehran Research Reactor (TRR). However, the nuclear deal ensures access to fuel for the TRR; the United States has issued waivers allowing those fuel transfers to continue even after re-imposing sanctions. A stockpile of uranium enriched to 20 percent would pose a more significant proliferation threat and reduce Iran’s breakout timeline.

Iran has also suggested that it could restart work on the unfinished heavy water reactor at Arak. If completed as originally designed, the Arak reactor could produce enough plutonium, when reprocessed, to provide fissile material for about two nuclear warheads per year. Under the JCPOA, Iran committed to modifying the reactor—with Chinese and U.S. (now British) assistance—to limit production to a fraction of the plutonium necessary for a bomb.

On July 3, Rouhani said construction on the reactor (as originally designed) will only restart if the remaining parties to the JCPOA do not fulfill commitments to assist in the modifications. The United States waived sanctions in May allowing cooperative work on the Arak reactor to continue but limited the waivers to 90 days (the waivers can be renewed at that time). Despite the U.S. actions, progress on Arak is proceeding, and earlier this year, China and Iran signed a new contract related to that project. When the parties to the deal met June 28 to discuss JCPOA implementation, they noted the progress on the Arak reactor and reaffirmed their commitment to a timely completion of the project.

Can the JCPOA be salvaged?

It may still be possible to save the nuclear deal, which since 2016 has successfully blocked Iran’s pathways to nuclear weapons. Iran will have to return to compliance; the remaining parties will have to facilitate legitimate trade with Iran and pressure the United States also to comply with its commitments. These steps could then serve as a foundation for Washington and Tehran to negotiate a follow-on nuclear agreement and potentially resolve other tensions in the region.

Kelsey Davenport is the Director for Nonproliferation Policy at the Arms Control Association.

Photo Credit: Rouhani via President.ir; Arak facility by Nanking2012 [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons