Garrett Nada

A gradual lifting of sanctions on Iran could reopen the Middle East’s second largest

economy (after Saudi Arabia) to U.S. and Western companies. Many European companies were active in Iran until 2010, but American companies have avoided doing business in the Islamic Republic for decades, either by choice or due to sanctions.

As negotiators from Iran and the world’s six major powers work to finalize a nuclear deal by June 30, businesses are investigating their prospects in Iran. An agreement that lifts even some sanctions might, over time, allow American firms access to a consumer-rich market.

Iran’s population, at about 80 million, is the

third-largest in the region, after Turkey’s 81 million and Egypt’s 86 million. Its consumer base is also young and well-educated. And the middle class has had a taste for U.S. goods dating back to the days of the Shah.

However, if a nuclear deal is signed, international companies are unlikely to flood Tehran immediately. The lifting of sanctions is likely to be a lengthy and uneven process for the United States and European countries. And some sanctions—imposed in response to alleged human-rights abuses and support for extremist groups by the Iranian government—will remain in place. The difficult business climate, rife with corruption, could be an additional obstacle.

Historical Context

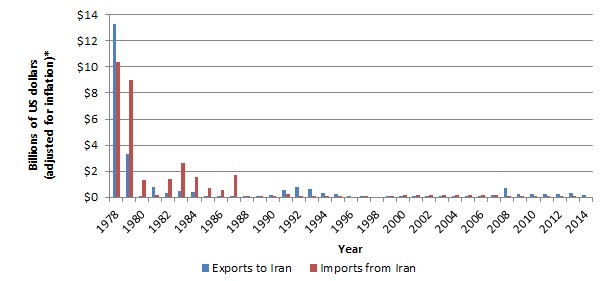

Before the 1979 revolution, the United States and Iran had a close relationship based on energy trade and common Cold War-era security priorities. Bilateral trade

peaked in 1978, when the United States

exported $3.7 billion worth of goods to Iran and imported $2.9 billion worth of goods from Iran.

On the eve of the revolution, the United States and West Germany were Iran’s largest trading partners. Nearly 50,000 Americans worked and lived in Iran. In turn, American goods—mainly arms, industrial equipment, technology, and agricultural and consumer goods—accounted for some 16% of Iranian imports. Iran bought between 50% and 75% of its imported rice, wheat, and cereals from the United States in the 1970s.

U.S.-Iran trade plummeted after the 1979 revolution, especially when American hostages were held for 444 days at the U.S. embassy compound in Tehran. The Carter administration

suspended Iranian oil imports in late 1979, and severed diplomatic relations with Tehran in 1980. But U.S.-Iran trade resumed in 1981 after the hostages were released. U.S.

exports totaled $300 million in 1981—down from $3.7 billion in 1978. Iranian exports to the United States totaled $64 million—down from $2.9 billion in 1978.

Through subsidiaries, American energy companies continued to buy Iranian oil—worth up to $3.5 billion a year—off the international market in Rotterdam until the mid-1990s, when sanctions were broadened.

Over the years, Washington has imposed waves of sanctions on Tehran over three broad issues: support for terrorism, failure to comply with United Nations on its nuclear program, and human-rights violations. Yet American companies have legally continued to export a wide array of goods under equally broad

exceptions that covered food, medicine, and humanitarian goods.

U.S. Interests and Non-Oil Trade

Trade has fluctuated from year to year. It dipped after the Clinton administration imposed new sanctions in

1995. But trade increased slightly in 2000 when sanctions on carpets and caviar were

lifted in modest outreach to Iran’s reformist government.

Major U.S. exports to Iran in recent years have included wheat, rice, soybeans, corn, dairy, pulpwood, plastics, medical equipment and pharmaceuticals. Iran is the region’s second-largest grain

importer after Saudi Arabia. U.S. exports to Iran in 2014 ranged from medical instruments to chocolate, even bull semen.

The following is a sampling of American products exported to Iran in 2014, which totaled $182.1 million:

Butter | $35,535,582 |

Non-electric medical instruments | $24,863,265 |

Seeds, fruits and spores (for sowing) | $19,992,618 |

Pharmaceutical products | $8,958,871 |

Bull semen | $8,036,388 |

Computers | $869,000 |

Essential oils, perfume and cosmetics | $827,892 |

Toiletries and cosmetics | $802,000 |

Chocolate and products containing cocoa | $253,970 |

Live Cattle | $216,000 |

Rice | $141,000 |

Plastic tableware and other household articles | $52,000 |

Live chickens | $46,197 |

Lamps, lighting fittings and parts | $34,673 |

U.S. and Western businesses are already interested in reentering the market. “Iran is the last, large, untapped emerging market in the world,” Ramin Rabii of Turquoise Partners, an Iran-based investment firm, told the BBC. About 65% of the population is under 35 years old, and literacyamong 15- to 24-year-olds is 98%. Total adult literacy is 85%. About half of all Iranian households reportedly have internet access.

As of 2013, the World Bank

classified Iran as an “upper middle-income” country. It

estimated that per capita income—based on purchasing power parity (PPP)—was $15,610. Even under sanctions, Iran’s economy has been the

second largest in the region, once again after Saudi Arabia, and its

gross domestic product (GDP) was ranked 32nd worldwide in 2013.

Iran’s consumer culture has long been heavily influenced by Western trends. Western-style grocery stores and shopping

malls have been gaining

popularity over the past decade. American and European luxury brands are popular with the elite in major cities, especially Tehran, because of their

reputations for quality.

Iconic beverage brands such as Coca-Cola and Pepsi have

prospered in Iran for years at the expense of local rival Zamzam Cola. The presence of bootleg versions of American

restaurants and coffee shops—from “Mash Donald’s” to “Pizza Hat”—suggests opportunities for U.S. franchises to expand and thrive.

American electronics brands, such as Apple and Dell, are still smuggled into Iran. Computer stores in Tehran are modeled after their U.S. counterparts and stock the latest merchandise. Apple iPods, iPhones, and iPads are particularly popular. An Iranian company that

resells Dell products even offers warranties. Both Apple and Dell reportedly

contacted potential Iranian distributors in 2014.

Iran is also one of the

largest car markets in the Middle East. American cars were popular before the revolution. General Motors

partnered with an Iranian company to produce cars for several years before 1979. The auto industry has historically been Iran’s largest non-oil industry. Domestic production

peaked in 2011, at about 1.6 million vehicles per year, before tightened sanctions cut off imports of car parts and bank transfers that halved output. But auto sales

rose 32% in 2014 over 2013. American cars and trucks have already

begun to make a

comeback.

With a female population of nearly 40 million, Iran is

reportedly the second-largest cosmetics market in the Middle East. For more than a decade, Iranian merchants have sold big American clothing brands, such as

Victoria’s Secret, in storefronts that mimic their U.S. counterparts—but without legal franchises.

Iran also represents a promising market for U.S. tobacco producers.

Marlboro has especially been popular for years. Until 2006,

cigarettesmade up a large share of American exports to Iran. Western brands are commonly

smuggled into Iran to meet demand. About a

quarter of Iran’s annual $11 billion cigarette imports are smuggled.

Until fall

2014, sanctions had prevented U.S. companies from selling aerospace parts to Iranian airlines. Iran Air’s aging

fleet includes 12 Boeing aircraft, some of which are more than 30 years old. Boeing’s small

sale of aircraft manuals, drawings and navigation charts to Iran Air in Oct. 2014 carried symbolic weight as the first publicly acknowledged transaction between U.S. and Iranian aerospace companies since the 1979 U.S. hostage crisis.

Iran has reportedly

signed three contracts with Boeing since an interim nuclear deal was negotiated in late 2013. Two were extensions of existing agreements and

one was a new contract between Iran Air and the American company. So far, Boeing has

repaired seven of Iran Air’s plane engines, according to Iran Air CEO Farhad Parvaresh.

American music and movies are still popular in Iran.

Bootlegging of Western tapes and later discs—especially of material that might otherwise be banned by the Iranian government for perceived immorality—has been common since the revolution. Smuggling DVDs and CDs has given way to illegal

downloading, so some movies are now sold on memory sticks on Tehran’s streets. The latest American releases, even ones still in theaters, are popular. If Iran and the United States were to recognize each other’s

copyrights, the American movie and music industries could benefit hugely.

Costs and Obstacles

For more than a year, Iran has been courting investors, hosting foreign trade

delegations, and dispatching envoys abroad to investigate new business opportunities. But Western businesses are not likely to enter Iran too quickly if a nuclear deal is reached. American companies may hesitate to make serious investments until they are convinced of the long-term durability of any agreement,

experts predict.

The complex layers of U.S. and European sanctions would also take time to unravel. Western sanctions linked to Iran’s support for terror and its human rights abuses will remain in place until Tehran’s behavior

changes. And some two dozen U.S. states have enacted their own punitive measures on companies operating in certain sectors of Iran’s economy, according to

Reuters. In more than half of those states, sanctions will remain in place unless Iran is removed from the list of state sponsors of terrorism or if all federal sanctions on Iran are lifted.

International companies that have operations in the United States and European Union risk facing sanctions or punitive fines if they move into Iran before sanctions are lifted. Violating sanctions can be expensive and damage a company’s reputation.

In 2014, the French bank BNP Paribas pleaded guilty to two criminal charges for violating sanctions against Iran, Sudan, and Cuba. It ended up agreeing to pay $9 billion to the U.S. government, a

record fine for violating U.S. sanctions. U.S. regulators banned the bank from conducting certain transactions in U.S. dollars for a year.

Western companies would also initially face difficulties starting businesses or partnerships in Iran. Widespread corruption and significant government involvement in the economy have created a challenging business environment, even for European companies that were active in Iran before sanctions were ramped up in 2010. The line between the private and

public sector also is not always clear because the Revolutionary Guards have affiliated companies working in many major industries.

Iran ranked 130 out of 189 economies in the 2015 World Bank

report on business regulations and property rights protections. The Islamic Republic performed worse than the regional average in most categories. It ranked 62nd for starting a business, 89th for acquiring credit and 172nd for obtaining a construction permit.

U.S. producers may face difficult obstacles to selling and investing, but the Iranian market is too large to ignore, especially given the dearth of other emerging markets with a middle class eager and able to buy imported goods. “I am already seeing a rush to market by U.S. and E.U. companies,” a director of the British-Iranian Chamber of Commerce told

The Wall Street Journal. “And no one wants to be left behind.”

Garrett Nada is the assistant editor of The Iran Primer at USIP. This article first appeared on Quartz.