Interview with Shervin Malekzadeh

Shervin Malekzadeh recently received his Ph.D. in Government from Georgetown University. His dissertation, based on nearly two years of research in Iran, deals with the politics of education in Iran and the ways in which efforts to produce the New Islamic Citizen through schooling facilitates both consent and protest to state rule.

- How have textbooks changed since the 1979 revolution?

Under the monarchy, Iran’s curriculum promoted a secular, pre-Islamic, and purely nationalist Persian identity. In contrast, the Islamic Republic’s textbooks teach children that they are Muslims and members of a worldwide community of believers steadfastly united in opposition against the West’s imperialist powers. But textbooks cannot be neatly divided into "before" and "after" the revolution, especially since books in the first years of post-revolutionary rule were inconsistent—and not always “Islamic” in character.

The regime has introduced political Islam into elementary textbooks in fits and starts over the past 30 years. In the early 1980s, the revolution was not fully identified in textbooks as Islamic; the adulation of revolutionary leader Ayatollah Khomeini was also less definitive. Radicalization of the texts only began between 1986-1988, eight years after the revolution. Islamist fervor peaked during this period of heightened militancy, which stretched into the middle of the 1990s. Textbooks then began a long period of moderation.

Education lacked cohesion and consistent standards. So the curriculum has been subject to the whims of rotating political leaders---although, oddly, revisions to the textbooks appear to have little to do with the actual political situation in Iran. For example, moderation begins under President Hashemi Rafsanjani and is well established before reformist President Mohammad Khatami took office.

- How much focus do textbooks give to Islam?

A study of Iran’s textbooks reveals one striking tendency: Books with religious intent also often use Islam for profane needs. For example, authors of the 1988 first grade primer justify nationalism by quoting the Koran: “The Prophet of Islam has ordered: ‘Loving one’s homeland is a sign of religious faith.’”

The evolution is reflected in the elementary school primer “Welcome to the Second Grade.” The 1979 version shows a homeroom teacher wearing a headscarf and modest dress. She welcomes children to the new school year, with little mention of God or Islam.Three years later, Islam is much more prominent, signaled by the lesson’s new title, “In the Name of God the Forgiving and Kind, Welcome to Second Grade.” By 1982, the teacher’s headscarf is gone, replaced by the tight-fitting maghnaeh, or fitted hood. In the updated version, the teacher talks almost exclusively about God’s importance and the centrality of worship to coming endeavors during the school year.

The 1987 version shows a mother—who in earlier versions was dressed in pink hejab, a blouse and skirt—now covered with a full-length black chador. The 1987 version also shows two columns of children converging into a single mass—the young girls in full-length chadors while the boys raise their fists high. The message is a declaration of support for the revolution: “We with faith in God, with purity and honesty, with gainful knowledge, with hard work, sacrifice, and thrift, independence, freedom, and the Islamic Republic do defend.”

- How have textbook themes changed in recent years?

In the mid-1990s, textbook themes shifted from an emphasis on a muscular and uncompromising political Islam to more practical everyday issues. Even revolutionary leader Ayatollah Khomeini, once portrayed as a fiery revolutionary, was recast as the “kind leader” and “grandfather” of the nation. Instead of pushing revolutionary dogma, one textbook admonished young people to avoid dangerous activities, including playing with knives, touching a hot pot, jumping into a fire and touching a meat grinder. The message read: “Kids be careful.” Another version showed children playing sports, accompanied by the slogan “Everybody exercise together.” The realities of life had begun to supersede religious dogma.

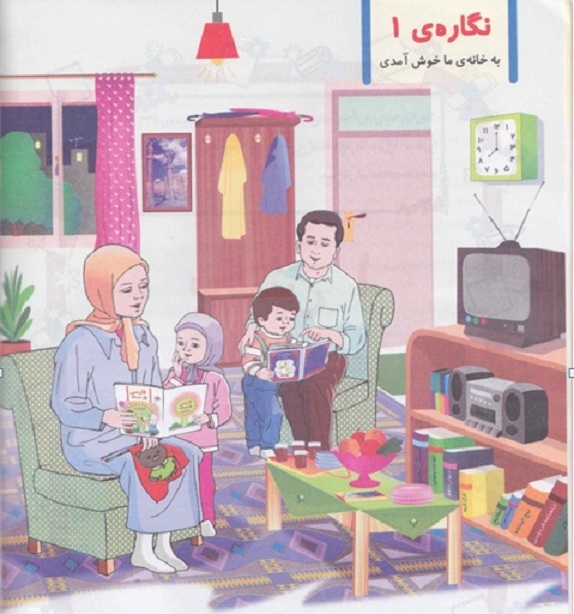

Today, elementary textbooks are the reconciling Iran’s pre-Islamic and Islamic identities, its Persian and Muslim pasts. On the first page of the first-grade textbook, a family reads together. [See picture.] A framed picture of the ancient ruins at Persepolis is clearly visible on the wall behind them. A bookshelf shows volumes of the epic poems by Iran’s famous medieval poets, Hafez and Ferdowsi, as well as the Koran and works by Khomeini.