Since 2002, Iran, Russia and India have worked intermittently on a new transportation system by rail, road and sea—running 4,500 miles through at least six Eurasian countries and benefitting seven others—that could be a game-changer for global trade. The goal of the joint project is to cut travel costs by up to a third and shipping time by nearly a half. It could eventually provide major commercial links between Asia and Europe.

The corridor mainly benefited Tehran, Moscow and New Delhi, but it had the potential to transform trade and commerce between Europe, the Middle East and Central Asia by tapping into existing routes to 11 other countries. Since 2003, the following countries have joined as partners: Azerbaijan, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Oman, Syria, and Ukraine, with Bulgaria as an observer.

The corridor had three primary arms:

- A land-and-sea route–known as the Trans-Caspian–runs from northern Russia across the Caspian Sea to southern Iran for shipment through the Strait of Hormuz into the Arabian Sea or the Indian Ocean. It was first used in 2022.

- A rail-and-road land route–known as the Western branch–runs from northern Russia south through Azerbaijan into northern Iran and then to a southern port on the Persian Gulf for shipment again by sea. The Western branch was not complete as of mid-2023.

- The latest rail-and-road route–referred to as the Eastern branch–runs from northern Russia southeast through Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan to Iran for shipment to India. It was first used in 2022.

The corridor “will help to significantly diversify global traffic flows, and provide “obvious economic benefits” for both countries, Russian President Vladimir Putin told President Ebrahim Raisi in May 2023. “Income, derived from freight deliveries via the North-South Corridor, as well as the more intensive operation of our states’ ports, will help establish related businesses and facilitate their growth.” Putin predicted that the project would in turn create jobs and improve the investment climate in both Russia and Iran.

In 2022, annual commercial traffic on all parts of the corridor carried 20,000 containers of oil, grain, lumber, and metals totaling more than eight million tons–up 65 percent from 2021, according to the Russian Ministry of Transport. The corridor had a “decisive role in changing the geometry of goods transiting in the region,” Ali Shamkhani, secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, told Igor Levitin, a Putin aide, during talks at the Kremlin in April 2023.

Despite two decades of development, however, the project was still far from being fully operational and able to replace the existing international trade routes. Historically, the corridor had not been a high priority, especially for Russia. Investment was erratic. In early 2022, Tehran publicly complained that Moscow had failed to develop the requisite port facilities along the Caspian needed to ferry goods into Iran. And U.S. sanctions on Iran, reimposed in 2019, made other nations wary of participating for fear of facing American financial penalties.

Iran

Iran has sought new trade partners and safer routes to export to get around tough Western sanctions. Tehran has particularly wanted ways to export trade with the 10 Russian cities (each with a population of more than 1 million) along the Volga River, an international commercial route that dates back to the Middle Ages.

By late 2022, Iran had committed to building at least 11 infrastructure projects, including roads, railways and seaports totaling almost $13 billion, which accounted for one-third of all investments by seven countries. Russia committed only slightly more. In late 2022, Iran estimated that it could generate $20 billion annually as a regional hub upon completion of the project.

But the corridor did not solve Iran’s “immense economic challenges in the short and medium term,” including rampant inflation, mounting sanctions, high unemployment, and government mismanagement,” Henry Rome of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy told The Iran Primer. Use of the route will only pay off in the long-term—if at all—since far more investment and construction is needed, Rome said. Estimated dates for completion vary between 2025 and 2030.

In the end, Iran may be little more than a transit stop that primarily helps Russia expand trade with India and other countries—and offers less to Iran, Alex Vatanka of the Middle East Institute told The Iran Primer. In 2022, Russian trade with India totalled $38 billion, which far surpassed its trade of $5 billion with Iran.

Russia

Russia sought alternative trade partners when it lost access to European markets after its invasion of Ukraine. In 2022, Russia’s imports from Europe were cut by half, and Europe’s imports from Russia plummeted even more. Creating a transportation network through Iran facilitated trade—notably for petroleum products, iron and other raw metals, and lumber—to energy-hungry South Asia and beyond.

By 2022, Russia had committed more than $13 billion to 52 infrastructure projects to enhance the North-South Corridor. They included roads, railways, seaports, border crossing points, maritime transport, and inland waterways. In May 2023, Putin signed an agreement to provide $1.7 billion to pay for a railway connecting Iran and Azerbaijan, a main connector along the North-South Corridor.

Yet the project has also faced “a thicket of geopolitical, economic, and logistical constraints,” Henry Rome of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy told The Iran Primer. “There's a contradiction at the heart of Moscow's plans. Russia seems to have a renewed interest in the corridor due to its geopolitical and economic isolation, widening Western sanctions have likely created new challenges, such as in financing the upgrades necessary to expand transit capacity.”

The Impact

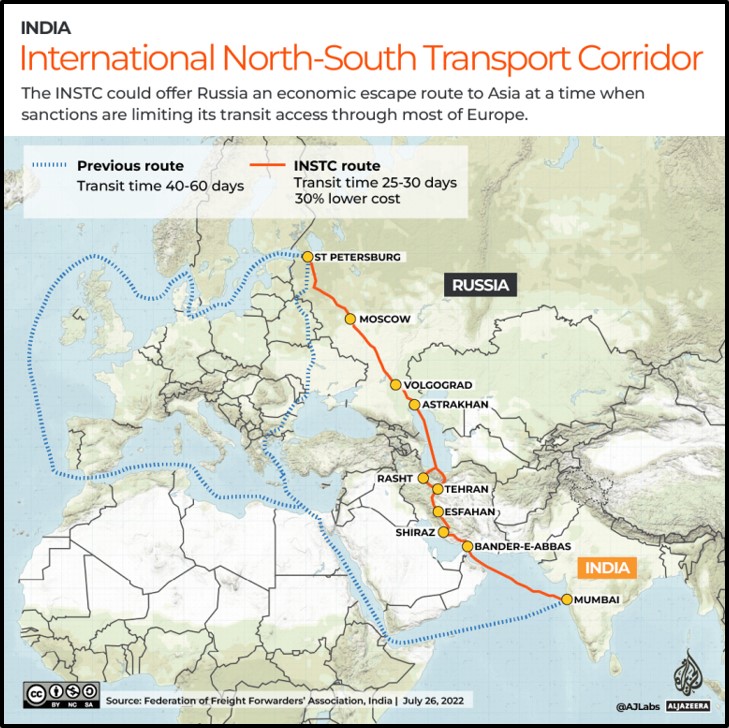

For more than a century, Russia had two far longer routes—that took 40 to 60 days—to export to the Middle East and South Asia. One route from Moscow or St. Petersburg went north to the Baltic Sea, circumvented Europe into the Mediterranean, crossed the Suez Canal, sailed around the Arabian peninsula or onto the Indian Ocean. The other went by land across Europe to South Asia, then picked up the shipping in the Mediterranean to the Suez Canal.

The first of several dry runs to test the North-South Corridor was in 2014; it traversed only parts of the corridor. The first full cargo run—with two containers of 41 tons of wood laminate—was shipped in June 2022. It started in St. Petersburg, traveled south by rail past Moscow to the Russian port city of Astrakhan on the Caspian Sea. It traveled by ship across the world’s largest lake to the Iranian port of Anzali. Trucks then carried the cargo by road from northern Iran past Isfahan and Shiraz to the southern port of Bandar Abbas for transfer by ship to Nhava Sheva, a port near Mumbai in India. The trip took 24 days.

Timeline

Sept. 12, 2000: Iran, Russia, and India established the International North-South Transport Corridor during the Euro-Asian Conference on Transport in St. Petersburg. They agreed to pursue “transportation cooperation among the Member States.” The three countries planned to connect the “Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf to the Caspian Sea via the Islamic republic of Iran…to St. Petersburg and North European via the Russian Federation.”

May 16, 2002: The North-South Corridor agreement went into effect after ratification by Iran, Russia and India.

Sept. 6, 2003: Kazakhstan joined the North-South Corridor agreement.

Jan. 10, 2004: Belarus joined the North-South Corridor agreement.

Dec. 8, 2004: Oman joined the North-South Corridor agreement.

Dec. 8, 2005: Tajikistan joined the North-South Corridor agreement.

Jan. 12, 2006: Azerbaijan joined the North-South Corridor agreement.

Feb. 22, 2006: Syria joined the North-South Corridor agreement.

April 11, 2006: Bulgaria joined the North-South Corridor agreement as an observer.

April 13, 2006: Armenia joined the North-South Corridor agreement.

March 2014: Indian conducted the first dry run of the corridor. India transported a small load from the port city of Nhava Sheva near Mumbai to Astrakhan, Russia.

Dec. 3, 2014: Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan and Iran announced the opening of a 578-mile railway line to connect the cities of Uzen in Kazakhstan, Bereket in Turkmenistan, and Gorgan in Iran. The line, part of the North-South Corridor, provided Kazakhstan with a rail link to the Persian Gulf.

Aug. 8, 2016: The presidents of Iran, Russia and Azerbaijan pledged to boost economic cooperation, including the completion of the North-South Corridor.

Dec. 2017: Azerbaijan announced a test run of the Astara-Astara rail line, a short segment of the corridor that connected Azerbaijan’s Astara province to the Iranian port city of Astara. About five miles of the railroad was in Azerbaijan, and a little less than one mile extended into Iran.

Apr. 13, 2017: India conducted another test run of the North-South Corridor. Goods were shipped from Nhava Sheva across the Arabian Sea to Bandar Abbas in Iran, transported by road to the port of Bandar Anzali, then shipped to the port of Astrakhan in Russia.

2018: Iranian media reported that a total of 11 million tons of goods were shipped along the corridor in 2018.

Mar. 6, 2019: Iran opened the Qazvin-Rasht railway line, a 109-mile line linking the cities of Qazvin and Rasht in northern Iran and an important part of the North-South Corridor.

Jan. 18, 2021: Iran and Azerbaijan signed an agreement to expand railroad cooperation. The goal was to increase the cargo volume transported between the two countries from 480,000 tons in 2020 to two million tons per year in the future.

October 2021: India proposed connecting Chabahar, a port in southeastern Iran on the Gulf of Oman, to the North-South Corridor. In 2018, India had committed to investing $85 million in the port, which could connect India to Afghanistan and Central Asia via Iran while bypassing regional rival Pakistan.

January 2022: During President Raisi’s trip to Moscow, Iran reached an agreement with Russia to open a $5 billion credit line to fund several infrastructure projects in Iran, including the construction of the Rasht-Astara line connecting Azerbaijan and Iran.

June 11, 2022: Russia transported its first cargo shipment–41 tons of wood laminate–on the North-South Corridor across the Caspian Sea through Iran and then by sea to India. The trip took 24 days.

Aug. 22, 2022: Customs authorities from Azerbaijan, Iran and Russia signed a memorandum to facilitate shipping among the three countries. “This document is to promote simplification and acceleration of customs procedures,” said a Russian trade official.

September 2022: Turkmenistan joined the North-South Corridor agreement.

November 2022: The Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines (IRISL) announced that it was investing $10 million in Russia’s Astrakhan port. Russia used the money to develop the port and purchase ships capable of carrying 270 containers.

March 2023: Armenia proposed the establishment of a Persian Gulf-Black Sea corridor to connect India with Russia and Europe and to remove Azerbaijan from the existing corridor.

April 20, 2023: The foreign ministers of Armenia, Iran, and India met in Yerevan to discuss deepening trade and economic relations.

May 17, 2023: President Putin and President Raisi signed an agreement on financing the Rasht-Astara railway, a key missing link in the corridor. The 100 mile-long railway would connect Iran and Azerbaijan. Russia committed to investing 1.6 billion euros ($1.7 billion) in construction while Iran was seeking investment to cover its portion of the project, projected to cost 4.6 billion euros ($5 billion). The goal was to complete construction within four years.

Picture Credits: North South Corridor 2 via Eurasian Development Bank