Since the early 21st century, the centerpiece of relations between Tehran and Beijing has been economic, largely based on trade in oil and consumer goods. China bought Iran’s oil to fuel industrialization, while it sold machinery, electronics, and appliances to Iran to expand its global marketplace. The relationship, however, has been lopsided.

From 2013 through 2022, China was Iran’s most important trading partner. But Iran was only China’s 50th largest trade partner in 2022. “The economic relationship is fundamentally asymmetrical, so I’d call it a one-way strategic partnership,” Henry Rome of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy told The Iran Primer. “It’s certainly strategic for Iran: China is Iran’s most important economic partner and is the lung through which the economy breathes, while Iran is one of many sources of energy and other trade for China.”

In one of many ironies about ties, the United States — which the Islamic Republic calls “the Great Satan”— has long been one of China’s most important economic relationships. Most of Iran’s regional rivals, including Israel, have far larger trade with China. In 2022, Russia did 12 times more trade with China.

Iran has long sought deeper ties. “The development of relations between Iran and China has been moving forward,” President Raisi told President Xi Jinping during a visit to Beijing in February 2023. “But what has been done is far from what should be done, and to compensate this backwardness, we should take greater steps.”

Iran has been keen on drumming up Chinese investment as part of the broader economic relationship. But “the gap between Iranian expectation and reality is vast, especially when it comes to China’s willingness to invest in the Iranian market,” said Rome. In 2022, Russia overtook China to become the largest investor in the Islamic Republic. Moscow invested $2.76 billion in Tehran during the Iranian fiscal year (from mid-March 2022 to mid-March 2023). China, in comparison, invested only $131 million in Iran the same year.

Iran has been keen on drumming up Chinese investment as part of the broader economic relationship. But “the gap between Iranian expectation and reality is vast, especially when it comes to China’s willingness to invest in the Iranian market,” said Rome. In 2022, Russia overtook China to become the largest investor in the Islamic Republic. Moscow invested $2.76 billion in Tehran during the Iranian fiscal year (from mid-March 2022 to mid-March 2023). China, in comparison, invested only $131 million in Iran the same year.

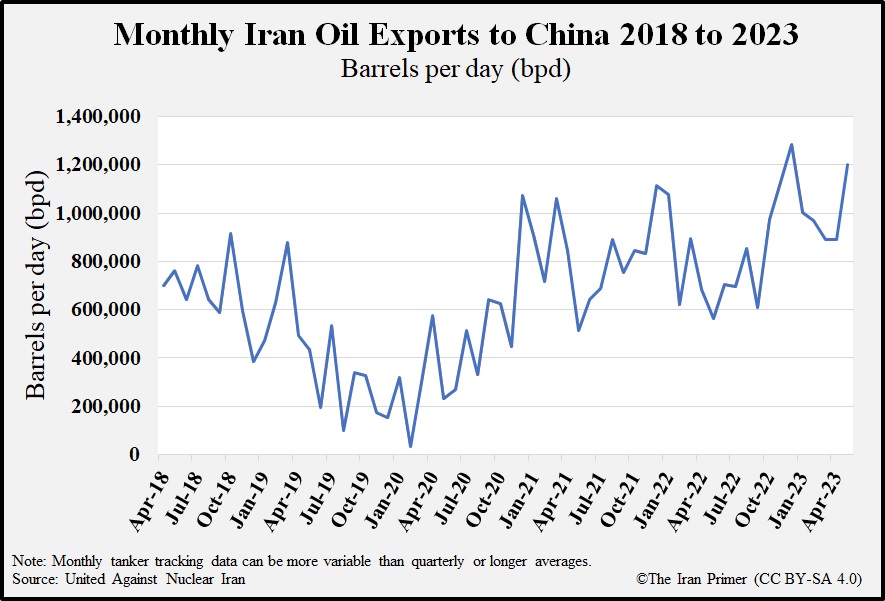

Trade with China has been particularly important for Iran since 2018, when the United States withdrew from the nuclear deal and reimposed more than 1,500 economic sanctions on Tehran. Since then, China’s oil purchases have provided Iran with “enough revenue to stay afloat,” Alex Vatanka of the Middle East Institute told The Iran Primer.

In 2021, Iran and China signed a 25-year “strategic cooperation agreement” to deepen economic and security ties, but little was implemented. In 2023, the two countries signed 20 additional memos of understanding on trade, transportation, technology, tourism, agriculture, and crisis response to take more specific steps on the earlier accord.

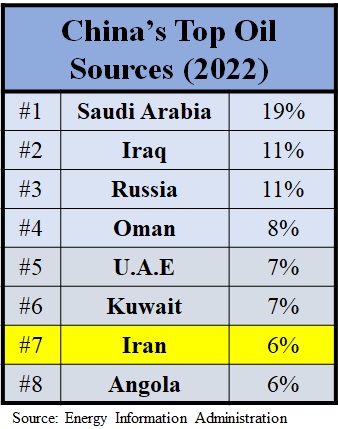

Yet the Islamic Republic has not yet become an important trade partner for China, Dawn Murphy from the National Defense University told The Iran Primer. China has increasingly diversified oil imports, not just because of the risk associated with Iran under U.S. sanctions, but also to prevent becoming “too reliant on any one supplier.”

Yet the Islamic Republic has not yet become an important trade partner for China, Dawn Murphy from the National Defense University told The Iran Primer. China has increasingly diversified oil imports, not just because of the risk associated with Iran under U.S. sanctions, but also to prevent becoming “too reliant on any one supplier.”

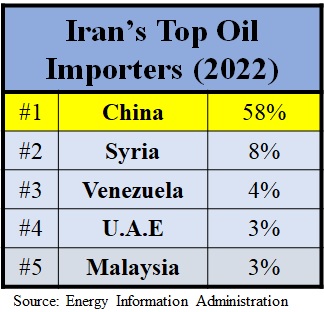

Its companies buy larger quantities of oil from Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Russia, Oman, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates—and the same amount as it buys from Angola.

Evolution

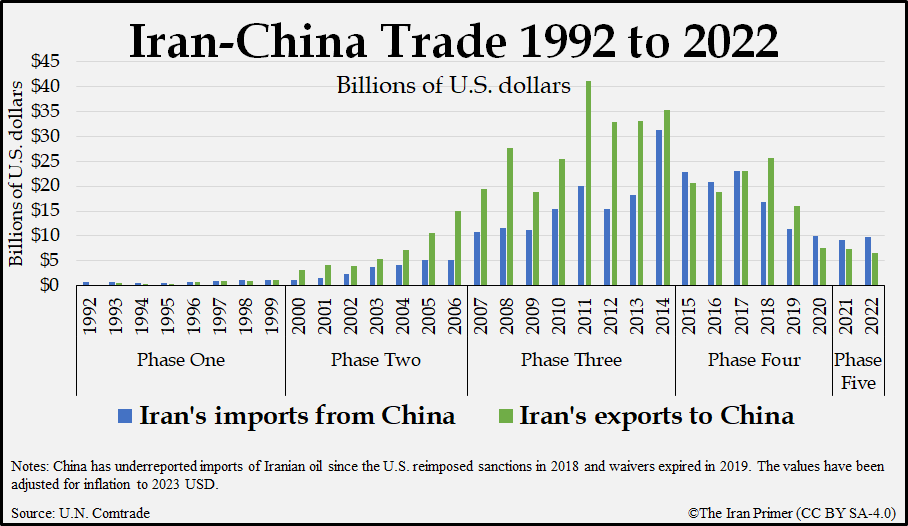

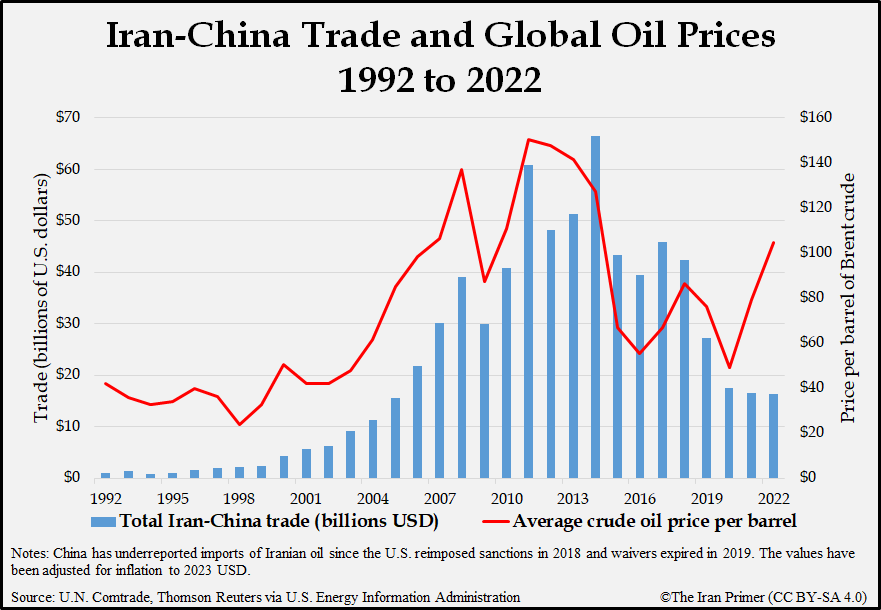

Trade between Tehran and Beijing has fluctuated in five phases since the 1979 revolution. It skyrocketed from $944 million in 1992 to $66 billion in 2014 (adjusted in 2023 for inflation). The turning point in economic ties was in 2007, partly as Iran bought more goods from China.

But economic ties then slumped between 2015 and 2022, according to Chinese government statistics. The global price of oil dropped, thus decreasing the profits of petroleum products for Iran. After Washington reimposed sanctions in 2018, Beijing also started underreporting its imports of Iranian oil to skirt U.S. sanctions on third parties dealing with Iran, which skewed government import data.

Since 2019, the Chinese market has been an important means of generating badly needed foreign exchange and evading U.S. sanctions. Between January and May 2023, Iran exported an average of roughly one million barrels of oil per day to China, according to United Against Nuclear Iran, a New York-based policy group.

Chinese companies bought Iranian oil—often through intermediaries in Malaysia and the United Arab Emirates—to prevent being sanctioned by the United States. They bought Iranian oil at a deeply discounted rate—reportedly some 40 percent lower than market prices in early 2023.

Between January and May 2023, non-oil trade between Iran and China remained the same as in 2022. But, again, it was lopsided. Iran imported 40 percent more from China—$4.6 billion worth of goods—compared to the same period in 2022. But Iran’s exports to China (excluding oil, which was excluded from official statistics) plummeted by 68 percent.

Iran’s hopes have fallen short partly because of bureaucratic challenges, mismanagement and corruption as well as “a real lack of economic vision,” Vatanka said. Trade also did not increase because many in the Iranian business community and public still preferred Western goods. Iranian officials were sometimes not satisfied with China’s follow-through in implementing agreements too.

Trade also has not increased because Beijing has backed certain U.N. sanctions over Tehran’s controversial nuclear program and wanted to avoid running afoul of U.S. restrictions. “China attempted to comply out of fear of secondary sanctions on their companies,” Murphy said. Beijing also “deeply valued relations with the United States” and did not want to be seen as “infringing on vital U.S. interests in the Middle East.” China was “very open to trading with Iran, but sanctions “definitely tamped down” bilateral imports and exports, she added.

Iran’s consumer market has not been as attractive as other countries with higher per capita GDPs. Chinese businesses looked to export items, such as advanced electronics and vehicles, with large profit margins. But the purchasing power of Iranian households has decreased, in part due to U.S. sanctions. As of 2022, some 60 percent of Iranians were reportedly living at or below the poverty line.

China also sought to prioritize other economic opportunities in the Middle East. Its “priority was Gulf countries” because there were fewer implicit dangers and better business prospects, Vatanka said. Beijing was “not in a rush” because Tehran “remained isolated” on the global stage. The Islamic Republic had few alternatives. China did not have to “chase” the Iranian market as a result.

Phase One: 1979 to 2000

Trade between Iran and China was minimal for the first two decades after the 1979 revolution. Iran bought Chinese arms worth billions of dollars during the eight-year war with Iraq in the 1980s. The warplanes, weaponry and tanks included J-6 fighter aircraft, T-59 and T-69 tanks, and Silkworm antiship missiles that were used against U.S. and Kuwaiti ships in the Persian Gulf. But non-military trade was limited. In 1992, it was less than $1 billion.

China had two considerations in arming Iran that had less to do with profits and more to do with strategic opportunities. First, Beijing shared Tehran’s intense anti-American policies after the revolution, according to Bates Gill, a China expert, in an analysis for the Middle East Review of International Affairs in 1998. Second, China sought to counter the Soviet Union’s strategic influence in the Middle East.

But China also armed Iraq during what was then the longest modern war in the region. Beijing claimed neutrality in the war—but played both sides. “There wasn't a big difference in the quality of arms provided to either side,” Murphy said. “It's just they were willing to provide what the two belligerents desired to purchase for the conflict.”

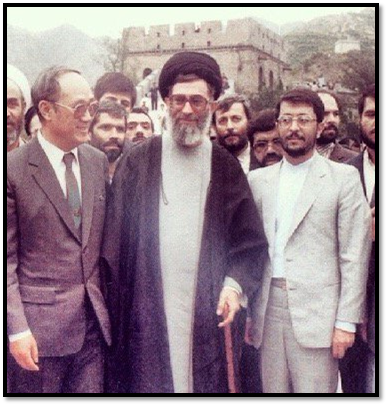

In May 1989, then President Ali Khamenei (just weeks before he became supreme leader) visited China in his first trip abroad as Iran’s top official. He stressed the need for more exchanges to realize the “untapped opportunity” for the relationship. Ties “must not remain limited to the areas of communication and industrial, technological and scientific exchanges,” he told his cabinet after returning to Tehran. President Hashemi Rafsanjani traveled to Beijing in 1992 and secured a Chinese commitment to provide Iran with two nuclear power plants. “Our cooperation with China has constantly been increasing,” he said, although the sale was delayed and eventually suspended in 1995.

At the end of the 1990s, commerce increased during China’s ambitious push to industrialize, which depended on new oil imports to fuel construction and production. Its oil consumption nearly doubled between 1990 and 2000. In 2000, its annual trade with Iran hit $4 billion.

Phase Two: 2000 to 2006

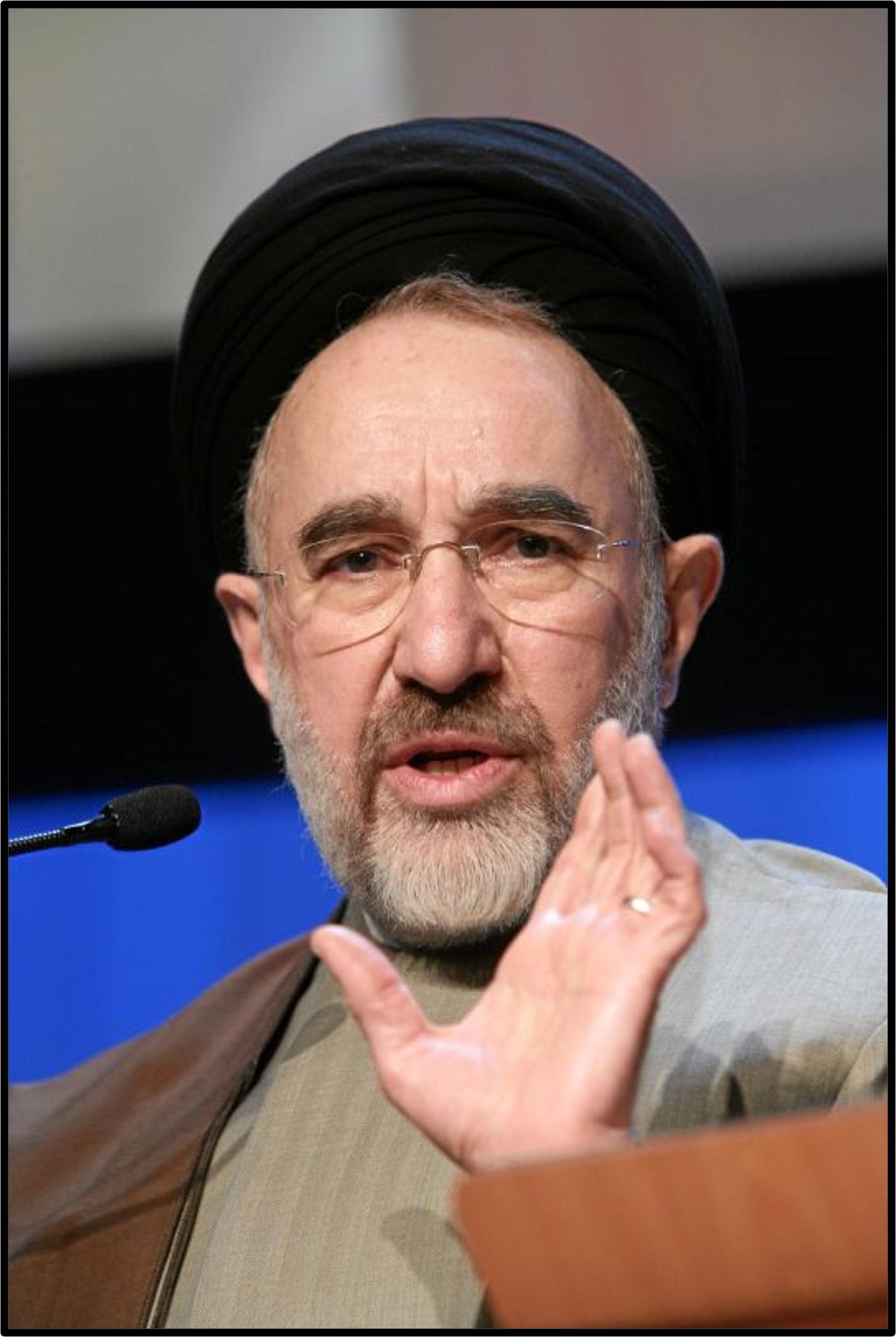

In June 2000, President Mohammad Khatami became the third Iranian president to visit Beijing to bolster energy, economic, political, and military ties. A joint communique said the two nations were on a “dynamic track, despite the enormous changes in the international situation” after the Cold War’s end. They charted a “common understanding” to enhance cooperation in the 21st century.

The two nations agreed “the Silk Road had laid a solid foundation for cultural exchanges between the ancient civilizations of China and Iran in east and west of Asia,” the statement said. The revitalization of the Silk Road “would contribute significantly to the consolidation and development of the cultural, art, tourist and people-to-people exchanges and contacts between the two peoples.”

In April 2002, President Jiang Zemin reciprocated with a visit to Tehran. It was partly a show of solidarity just weeks after President George W. Bush labeled Iran as one of a troika of nations in the “axis of evil.” But China’s primary strategic interest was its growing in access to oil. During the second phase, trade picked up as China bought more Iranian oil. Iran, in turn, bought more consumer goods.

By the end of 2006, trade between the two Asian powers totaled $22 billion. China imported more than $15 billion from Iran, while Tehran imported more than $5 billion from Beijing.

Phase Three: 2007 to 2014

Trade fluctuated during the third phase because of gyrating oil prices and the global recession in 2008-9. During this period, international sanctions on Iran tightened after it refused to stop enriching uranium and cooperate with the U.N. nuclear watchdog.

But trade between the two nations trended upward as Tehran turned to China as one of the limited places willing to build economic ties. Chinese firms were early replacements for Western companies that began divesting from Iran in the late 2000s due to international sanctions. In 2011, China surpassed countries in the European Union for the first time as the top importer of Iranian oil. It averaged 2.5 million barrels per day.

Beginning in 2013, Iran and the world’s six major powers began two years of negotiations to end the international crisis over Tehran’s nuclear program. The interim Joint Plan of Action (JPOA) implemented in January 2014 suspended some U.S. and European sanctions on Iran as part of confidence-building in the diplomacy.

The partial lifting of sanctions allowed China, legally rather than secretly, to increase purchases of Iranian oil by 28 percent. The repatriation of Iranian financial assets—previously frozen by sanctions—also allowed Iran to import more goods from China. For the first time, Iran’s imports from China almost reach parity with its exports to China.

The third phase marked the highest level of trade between the two Asian powers. In 2007, trade had totaled $30 billion in 2007. By 2014, it doubled to $66 billion.

Phase Four: 2015 to 2020

Trade between Iran and China plummeted during the fourth phase, as oil prices crashed in 2015 and Beijing bought less oil from Iran. In 2015, trade totaled $43 billion. By 2020, it dropped to less than $18 billion—down to the level in 2005.

In 2016, the conclusion of two years of tough diplomacy between Iran and the world’s six major powers—which produced the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)—opened new potential for trade, as U.N. sanctions were lifted. The nuclear deal allowed Iran to return to the global market.

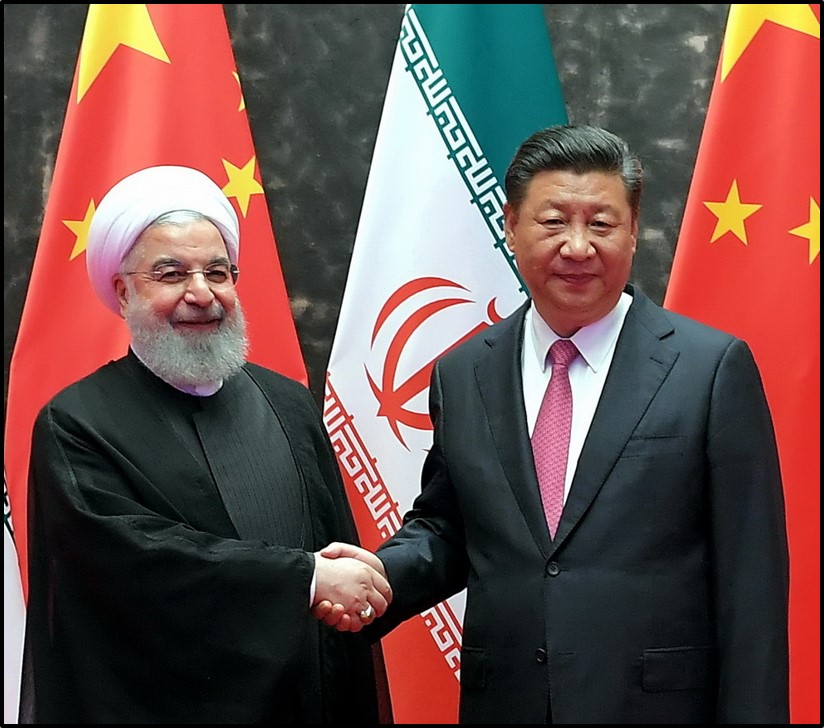

In January 2016, President Xi Jinping flew a large business delegation to Tehran just days after the deal was implemented. “China has always stood by the Iranian nation during hard times, and this amicable behavior is an asset that we should use to develop bilateral relations more than before,” President Hassan Rouhani told Xi, the first Chinese president to visit in 14 years.

“Geographically, Iran has the capacity to become a hub for China’s economic activities in the Middle East and Central Asia and Caucasus,” he said. Iranian and Chinese officials signed 17 agreements in energy, industry, transportation, technology, and other fields.

Yet trade dropped further in 2019, a year after President Donald Trump withdrew from the nuclear accord and reimposed sanctions on Iran. China’s waiver to purchase Iranian oil expired in May 2019, which exposed it to U.S. financial penalties for importing oil from the Islamic Republic. Trump’s policy of “maximum pressure” led Tehran increasingly to focus on foreign policy on the East.

In 2020, the outbreak of COVID-19 also drove oil prices lower. The virus emanated from Wuhan, China, but Qom, the Iranian holy city near Tehran, became one of the first epicenters of the global pandemic. With industry and society under lockdown, China’s global crude oil imports declined by some eight percent between January and April 2020, the initial pandemic shock, compared to the same period in 2019. Iran’s oil exports to China declined by more than half—down from an average of 619,000 barrels per day between January and April 2019 to just 307,000 barrels per day in the same period in 2020.

Phase Five: 2021-

Trade became increasingly difficult to track as China underreported its purchases of Iranian oil to avoid U.S. sanctions. Its companies reportedly continued to buy Iranian oil through intermediaries, many in Malaysia and the United Arab Emirates. Iran’s oil exports to China notably trended upward during phase five. But Tehran was forced to sell its petroleum exports at discounted prices to lure businesses that feared U.S. financial penalties on third parties.

In March 2021, during the final months of Rouhani’s presidency, Iran signed a 25-year strategic agreement – focused largely on strengthening economic and security cooperation – with China. “China is a friend for hard times,” said Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said that China “firmly supports Iran in safeguarding its state sovereignty and national dignity.” During the announcement in Tehran, he called on the United States to abandon the Iran sanctions and “remove its long arm of jurisdictional measures that have been aimed at China, among others.”

Iran’s turn to the East accelerated after the election of hardline President Ebrahim Raisi. “Raisi and his team think that the 21st century belongs to Asia and rising powers there,” Nasser Hadian, a University of Tehran political scientist, told The Iran Primer. “Amid the shifting world order, they see China as the leader of an emerging Eastern bloc that includes Russia, Pakistan, and Iran.”

In 2021, Iranian oil exports to China reportedly averaged 818,000 barrels per day, although Beijing did not issue official numbers. For the first five months of 2023, it averaged about 1 million barrels per day.

On July 4, 2023, Iran was formally admitted as the ninth member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), a security and economic organization led by China and Russia, during an online summit hosted by India. President Ebrahim Raisi joined the proceedings with leaders from other member states, including India, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

In a joint declaration, the SCO called for a “multi-polar world order” and rejected ideological blocs in world politics. The statement condemned the “unilateral and unlimited expansion of global missile defense systems” and stressed the need to “establish an inclusive government in Afghanistan with the participation of representatives of all ethnic, religious and political groups in Afghan society.” The SCO also proposed a 2030 Economic Development Strategy and endorsed China’s Belt and Road Initiative, although India opposed the latter move.

By 2023, Tehran sought a strategic relationship with Beijing because of its status as a rising global power and a potential partner in offsetting the impact of Western sanctions. But China primarily viewed Iran as an energy source. Beijing also viewed Tehran as a way to balance its ties—and diversify energy sources—in the volatile Middle East.

Deepening ties with the Islamic Republic was also a means of ensuring stability in the Middle East, which China relied on for more than half its oil. Beijing worried that “extraordinary economic pain in Iran may translate into more aggressive behavior on the international stage,” which was a part of the reason for trade with Tehran, Murphy told The Iran Primer.

The United States as Iran’s Trade Rival

The biggest obstacle to Iran’s trade with China in the 21st century has been the United States—for its economic might and wealth, massive consumer base, and diplomatic clout.

The biggest obstacle to Iran’s trade with China in the 21st century has been the United States—for its economic might and wealth, massive consumer base, and diplomatic clout.

Economically, the United States became China’s largest trade partner in the 2000s. By 2022, trade between the world’s two largest economies totaled $759 billion—or 12 percent of China’s global trade. In contrast, China’s trade with Iran was slightly less than $16 billion—or 0.25 percent of China’s global trade.

Diplomatically, more than 1,000 U.S. sanctions on Iran—for its nuclear program, missile proliferation, support for terrorism, and human rights abuses—also deterred China from deeper economic integration. Chinese companies face third-party sanctions if they are caught buying goods from Iran.

Due to both factors, China has increasingly turned to trade with other Middle East countries. Its trade in 2022 with Saudi Arabia, Iran’s biggest rival in the Muslim world, was $67 billion—or four times larger than the almost $16 billion trade with Iran. China’s trade with Israel, Iran’s nemesis in the Middle East, was $25 billion—or 60 percent higher than trade with Iran. The Iran-China relationship was “still quite transactional,” Murphy said. “It is a decreasingly important economic relationship in comparison to other powers in the region. China wants Iran to feel included and not engage in destabilizing behavior.”

Photo credit: Khatami via World Economic Forum (www.weforum.org)