Since the 1979 revolution, the Iranian government has allegedly harassed, jailed, tortured and executed dozens of athletes – including world champions and Olympians. Some have been jailed or executed for criticizing or acting against the regime. During the first decade of the Islamic Republic, several athletes were reportedly executed for connections to the ousted monarchy or to leftist opposition groups. In subsequent years, others have been executed on flimsy evidence for allegedly working for Israeli intelligence and the Islamic State.

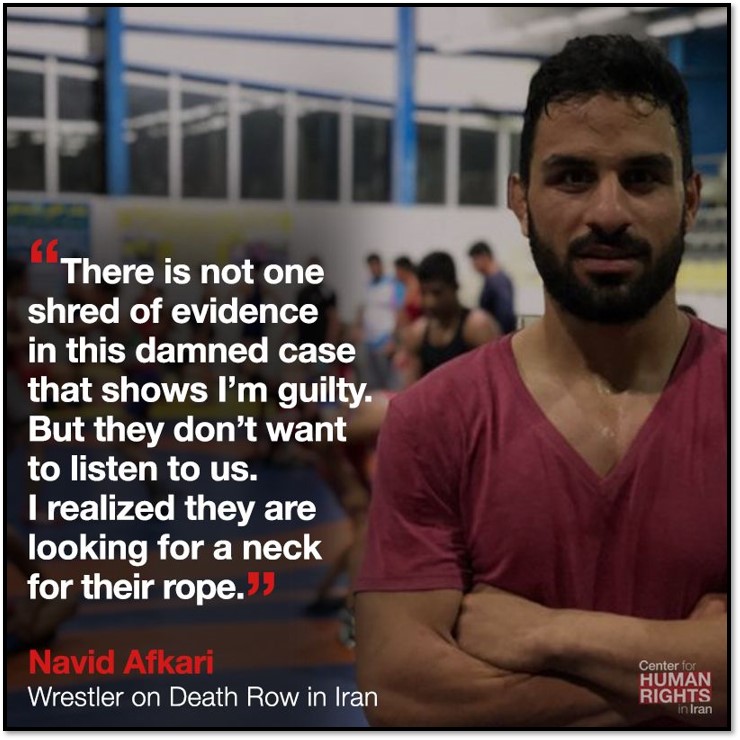

Some athletes have been targeted for taking part in anti-government protests. The most well-known case was the execution of Navid Afkari, a champion wrestler who participated in demonstrations in 2018. He was hanged in 2020 despite international criticism and evidence that he was tortured and forced to confess to murdering a security guard. “It is deeply disturbing that the authorities appear to have used the death penalty against an athlete as a warning to its population in a climate of increasing social unrest,” five U.N. human rights experts said in a statement.

Some athletes have been targeted for taking part in anti-government protests. The most well-known case was the execution of Navid Afkari, a champion wrestler who participated in demonstrations in 2018. He was hanged in 2020 despite international criticism and evidence that he was tortured and forced to confess to murdering a security guard. “It is deeply disturbing that the authorities appear to have used the death penalty against an athlete as a warning to its population in a climate of increasing social unrest,” five U.N. human rights experts said in a statement.

The episode sparked the establishment of United for Navid, a human-rights group that calls on international organizations to ban the Islamic Republic from sporting events. In spring 2021, United for Navid urged the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to exclude Iran from the Tokyo games. “Can IOC member states torture and arrest athletes and violate the [Olympic] charter?” asked Sardar Pashaei, a spokesman for the group. “Are you doing anything to protect these athletes? Because their rights are being discriminated against every single day.” Pashaei, a former junior world wrestling champion, said that he fled Iran in 2008 after authorities stymied his career due to his Kurdish ethnic identity and his father’s political activities.

Dozens of athletes have chosen exile after being mistreated by authorities based on their ethnicity, gender, religion, or political views. At the Tokyo Olympics in 2021, five of the 29 athletes on the IOC refugee team were Iranian.

Female athletes have often cited the strict Islamic dress code and sexism. Iran’s only female Olympic medalist, taekwondo fighter Kimia Alizadeh, defected in 2020. “I am one of the millions of oppressed women in Iran with whom they have been playing for years,” she wrote in an Instagram post announcing her decision to not return to Iran. “Kimia is voicing their [women's] frustrations and complete lack of respect from Iranian officials for their demands and grievances,” said Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of the Center for Human Rights in Iran.

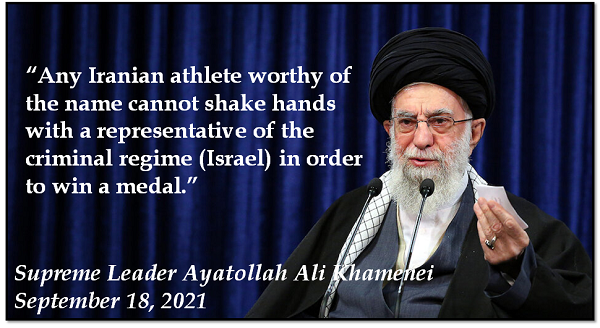

Some athletes have grown frustrated with the Islamic Republic’s policy forbidding athletes to compete against Israelis. After the 1979 revolution, the new regime cut diplomatic ties with Israel and subsequently supported Palestinian militant groups. For years, Iranian authorities have pressured athletes to lose matches to avoid matchups against Israeli competitors. The practice has disrupted careers and caused athletes to lose out on chances at medals at top competitions.

Some athletes have grown frustrated with the Islamic Republic’s policy forbidding athletes to compete against Israelis. After the 1979 revolution, the new regime cut diplomatic ties with Israel and subsequently supported Palestinian militant groups. For years, Iranian authorities have pressured athletes to lose matches to avoid matchups against Israeli competitors. The practice has disrupted careers and caused athletes to lose out on chances at medals at top competitions.

Judo fighter Saied Mollaei defected in 2019 after he was told to throw a match at the World Championships in Tokyo to avoid facing an Israeli. The International Judo Federation suspended Iran’s participation in competitions and all other activities over the incident (the ban was reversed in 2021). “I could have won my third World Championship medal. This is a burden that is hard for me to bear” Mollaei told DW. “Many athletes have left their country and left their personal lives there behind to pursue their dreams.” The following are profiles of athletes who have been executed and imprisoned or who fled Iran.

Executions

Ali Mutairi

Born in 1990, Ali Mutairi was a champion boxer and coach. Iran executed him on January 28, 2021 in Sheiban prison in southwestern Khuzestan province. Activists and family members alleged that Mutairi was tortured into providing a false confession to the murder of two Basij militia members on behalf of the Islamic State in 2018. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) said that Mutairi’s case was “tragic” but “clearly outside the IOC’s remit” because his participation in sports appeared to be irrelevant.

“We strongly condemn the series of executions, at least 28, since mid-December, including people from minority groups,” a U.N. spokeswoman said after Mutairi’s execution. Mutairi was an ethnic Ahwazi Arab. Arabs, largely concentrated in Khuzestan, are estimated to make up between two and four percent of Iran’s 84 million people. Activists have long complained of discrimination by the Persian-dominated central government. The Alahwazi Organization for Human Rights claimed that Mutairi was a political activist.

Navid Afkari

Born in 1993, Navid Afkari was a champion wrestler. Iran hanged him on September 12, 2020 at Adelabad prison in Shiraz. He was charged with “enmity against God,” insulting the supreme leader, and the murder of a security officer during protests over economic hardships and political repression in 2017-2018.

Afkari had long protested his innocence. In court and in a handwritten letter in 2019, he detailed repeated rounds of torture in two prisons that led to his forced confession. He described 50 days of beatings, attempts at suffocation, and having alcohol poured into his nose. In a final voice recording from prison, Afkari said: “I’ve exhausted all resorts to the justice system of the Islamic Republic. They’ve rejected my requests for a retrial. The Islamic Republic of Iran is about to execute an innocent person.”

The execution was condemned worldwide. Five U.N. human rights experts said that the execution was “summary…arbitrary [and] imposed following a process that did not meet even the most basic substantive or procedural fair trial standards, behind a smokescreen of a murder charge.” They called on the international community to “react strongly” to Iran’s actions. In the United States, Mike Pompeo, the Secretary of State at the time, called Afkari’s death “a vicious and cruel act” and “an outrageous assault on human dignity, even by the despicable standards of this regime.” In December 2020, authorities reportedly demolished the walls around Afkari's gravesite.

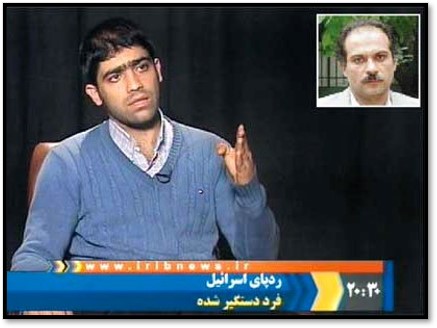

Majid Jamali-Fashi

Born in 1988, Majid Jamali-Fashi was a kickboxer. Iran hanged him in 2012 at Evin prison. He was arrested in 2010 for allegedly assassinating an Iranian nuclear scientist on behalf of Israel’s Mossad intelligence agency. “The defendant had traveled to Israel to receive training from Mossad and had agreed to assassinate Dr. Ali-Mohammadi in return for $120,000,” Tehran’s chief prosecutor claimed.

In a state television program, Jamali-Fashi confessed to training at a military base outside of Tel Aviv. The program also showed Fashi’s image on an Israeli passport that appeared to be fabricated using an image from Wikipedia, according to the BBC. Rights groups said that authorities tortured him into a false confession because of his prior public support for opposition leader Mir Hossein Mousavi. Amnesty International condemned the execution and the use of televised confessions, which “grievously undermines defendants’ right to a fair trial, in particular the presumption of innocence and the right not to be compelled to confess guilt.”

Mahshid Razaghi

Born in 1954, Mahshid Razaghi was a member of the national Olympic soccer team. Iran executed him in 1988. He was initially sentenced to one year in prison in 1980 for selling anti-government newspapers. But he was not released after serving his sentence. Razaghi was held in Evin, Ghezel Hesar, and Godhardah prisons. He was reportedly executed amid a massacre of thousands of political prisoners in 1988, according to a report published by Amnesty International in 2018.

In 2021, more than 100 Iranian athletes in the diaspora co-signed a letter urging the United Nations to hold President Ebrahim Raisi “to account by putting him and other officials of the clerical regime on trial for the 1988 massacre of political prisoners in Iran.” Raisi was a member of the so-called “Death Committee,” which planned and organized the execution of prisoners.

Foruzan Abdi

Born in 1957, Foruzan Abdi was the captain of the national volleyball team. Iran executed her in 1988. She was initially sentenced to five years in prison in 1981 for membership in the Mujahadeen-e Khalq (MEK), a militant opposition group that participated in the revolution but later broke with the new Islamic government over political and ideological differences.

Born in 1957, Foruzan Abdi was the captain of the national volleyball team. Iran executed her in 1988. She was initially sentenced to five years in prison in 1981 for membership in the Mujahadeen-e Khalq (MEK), a militant opposition group that participated in the revolution but later broke with the new Islamic government over political and ideological differences.

Abdi remained in detention until her execution at Evin prison. She was executed amid the same massacre of political prisoners as Razaghi.

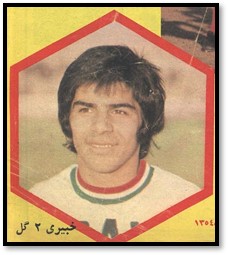

Habib Khabiri

Born in 1954, Habib Khabiri was a member of the national soccer team. Iran executed him in 1984. He was reportedly arrested in 1983 for allegedly being an MEK member.

Born in 1954, Habib Khabiri was a member of the national soccer team. Iran executed him in 1984. He was reportedly arrested in 1983 for allegedly being an MEK member.

Khabiri became a national hero after he scored a dramatic goal in the 1978 World Cup qualifying game against Kuwait. “Habib was the Iranian Kobe Bryant,” a former soccer announcer in Iran told Sports Illustrated in 1998.

Mahbubeh Parcham Kashani

Born in 1952, Mahbubeh Parcham Kashani was a gymnastics champion and Olympic judge. Iran executed her in 1982 or 1983. She was reportedly arrested in 1982 for being a member of the leftist opposition group “Rah-e Kargar.”

Hooshang Montazeralzohoor

Born in 1951, Hooshang Montazeralzohoor was a Greco-Roman wrestler. Iran executed him by firing squad in 1981. Authorities charged Montazeralzohoor with membership in the MEK.

Born in 1951, Hooshang Montazeralzohoor was a Greco-Roman wrestler. Iran executed him by firing squad in 1981. Authorities charged Montazeralzohoor with membership in the MEK.

Montazeralzohoor represented Iran in the 1976 Olympics in Montreal and at the 1977 Summer Universiade in Bulgaria.

Bahman Nasim

Born in 1940, Bahman Nasim was a member of the national swimming and water polo team. Iran executed him in 1980. He served as a police major under the monarchy and was charged with “shooting and killing innocent people.”

Nader Jahanbani

Born in 1928, Nader Jahanbani was an equestrian champion, pilot and director of the National Iranian Sports Organization. Iran executed him in 1979. He was found guilty of charges including acting against national security, moharebeh (enmity against God), and spreading “corruption on Earth” – vague charges often been levelled against supposed critics of the regime. “I have no particular defense, but I have never done anything against the revolution,” he said in court.

Born in 1928, Nader Jahanbani was an equestrian champion, pilot and director of the National Iranian Sports Organization. Iran executed him in 1979. He was found guilty of charges including acting against national security, moharebeh (enmity against God), and spreading “corruption on Earth” – vague charges often been levelled against supposed critics of the regime. “I have no particular defense, but I have never done anything against the revolution,” he said in court.

Jahanbani was apparently targeted due to his close association with the monarchy. He reached the rank of Lt. General in the Air Force.

Pending Execution

Mohammad Javad Vafaei-Sani

Born in 1995, is a local boxing champion and coach. Iran sentenced Mohammad Javad Vafaei-Sani to death on January 9, 2022. Authorities did not announce an execution date. Vafaei-Sani was reportedly detained in February 2020 and subsequently charged with “spreading corruption on Earth” in connection with arson and destruction of government buildings during anti-government protests in 2019.

Born in 1995, is a local boxing champion and coach. Iran sentenced Mohammad Javad Vafaei-Sani to death on January 9, 2022. Authorities did not announce an execution date. Vafaei-Sani was reportedly detained in February 2020 and subsequently charged with “spreading corruption on Earth” in connection with arson and destruction of government buildings during anti-government protests in 2019.

Defectors

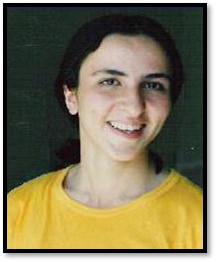

Kimia Alizadeh

Born in 1998, Kimia Alizadeh is an Olympian taekwondo fighter. She defected in January 2020. “I am one of the millions of oppressed women in Iran with whom they have been playing for years,” she wrote in a lengthy Instagram post explaining her decision. “My troubled spirit does not fit into your dirty economic channels and tight political lobbies.”

Alizadeh wrote that she could no longer tolerate the government’s “hypocrisy” and “injustice,” including the obligatory dress code. “Whatever they said, I wore. Every sentence they ordered, I repeated.” The government only cared about her medals and parading her around, she wrote. At the 2016 Olympics, Alizadeh won a bronze medal in taekwondo. As Iran’s first female Olympic medalist, she was regarded as a national hero.

Alizadeh first sought asylum in the Netherlands, where she was training, and eventually settled in Germany with her husband. In 2021, she competed as part of the refugee team at the Olympics in Tokyo. She lost in the match for the bronze medal.

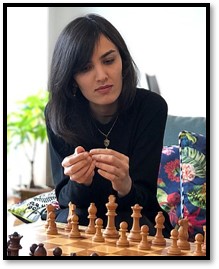

Mitra Hejazipour

Born in 1993, Mitra Hejazipour is a chess grandmaster. She removed her hijab during the World Rapid and Blitz Chess Championship in Moscow in December 2019. The following month, the Iran Chess Federation banned her from the national team. Hejazipour chose to stay in France in exile. “In my opinion forced hijab is a clear symbol of an ideology that considers women the second sex,” she wrote in an Instagram post. The dress code “creates a mountain of restrictions for women and denies them their most basic rights.” In 2021, Hejazipour was authorized to represent France in international competitions.

Born in 1993, Mitra Hejazipour is a chess grandmaster. She removed her hijab during the World Rapid and Blitz Chess Championship in Moscow in December 2019. The following month, the Iran Chess Federation banned her from the national team. Hejazipour chose to stay in France in exile. “In my opinion forced hijab is a clear symbol of an ideology that considers women the second sex,” she wrote in an Instagram post. The dress code “creates a mountain of restrictions for women and denies them their most basic rights.” In 2021, Hejazipour was authorized to represent France in international competitions.

Chess has been played in Iran since the 6th century CE. It was recognized as a sport by the IOC in 1999 and has a prestigious status in Iran.

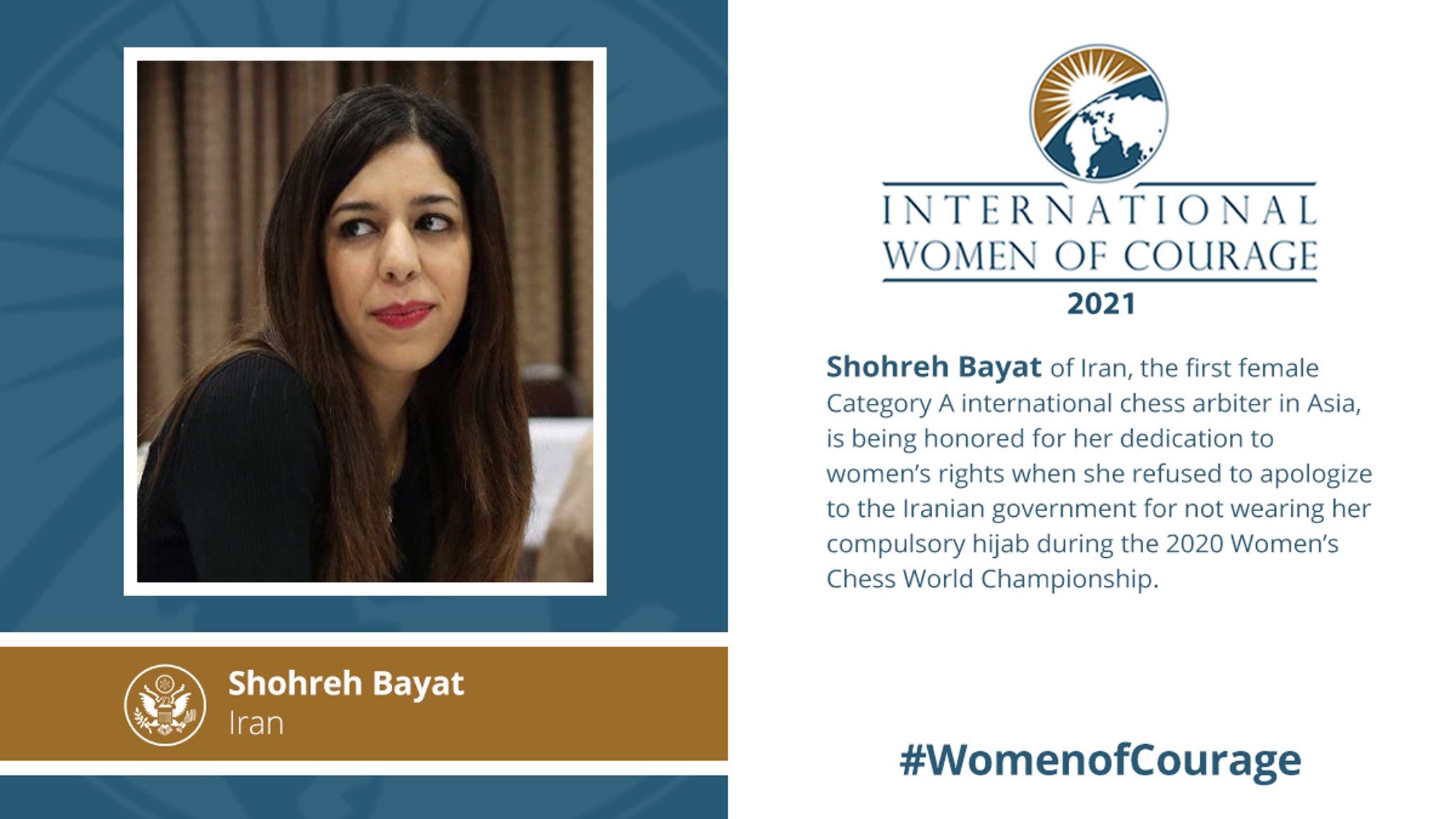

Shohreh Bayat

Born in 1987, Shohreh Bayat is a chess champion and world-class referee. She defected in 2020. She feared returning to Iran after images of her without a hijab at the 2020 International Chess Federation Women's World Chess Championship in Shanghai were circulated online. Bayat, the highest ranked arbiter in Asia, served as a referee at the competition. Bayat subsequently applied for asylum in Britain. “People must be free to choose to wear what they want, and I was only wearing the hijab because I live in Iran and I had to wear it,” she told CNN. I had no other choice.”

Bayat later told The Telegraph that she wanted to stop hiding her Jewish ancestry. “All my life was about showing a fake image of myself to society because they wanted me to be an image of a religious Muslim woman, which I wasn’t,” she said. “I knew I couldn’t tolerate it any longer.” Bayat became a national champion at age 12 and later headed the Iran Chess Federation. In 2021, Bayat received the State Department's International Women of Courage Award.

Saied Mollaei

Born in 1992, Saied Mollaei is an Olympian judoka. He defected in 2019. He received a two-year visa for Germany and then gained Mongolian citizenship. Mollaei claimed that he was ordered to throw multiple matches to avoid facing Israeli opponents. His coach told him to lose a match at the 2019 World Judo Championships in Tokyo so that he wouldn’t fight Sagi Muki. The International Judo Federation suspended Iran over the incident. “I just want to be courageous and live freely,” he told DW. “I don’t care whether I am facing a judoka from Israel or any other country.”

At the 2020 Olympic games, Mollaei represented Mongolia and won the silver medal in the men’s 81-kilogram division. Mollaei dedicated his win to Israel, where he trained and had even befriended Muki.

Amir Mohammad Shahnavazi

Born in 1997, powerlifter Amir Mohammad Shahnavazi defected to France in 2019 to protest Iranian-state corruption and discrimination against him and other members of the ethnic Baluch minority. Baluch activists have long alleged that the central government has tried to suppress Baluch identity and neglected Sistan and Baluchistan province.

“Even for wearing your Baluchi ethnic garment, you might confront problems,” Shahnavazi told Radio Farda. Shahnavazi claimed – in a video for United for Navid – that he was barred from attending some international competitions due to his ethnicity. Shahnavazi won the Asian silver medal for press lift in the 83-kilogram class in 2018.

Alireza Firouzja

Born in 2003, Alireza Firouzja is a chess grandmaster. He defected in 2019 after forfeiting a game against an Israeli player at the 2019 GRENKE Chess Open in Germany. Ahead of the 2019 World Rapid & Blitz Chess Championship, he told the Iran Chess Federation that he wanted to change his nationality. He competed under the flag of the International Chess Federation, apparently to be able to play against Israelis, and won the silver medal. Firouzja and his father were living in France at the time.

Firouzja gained French citizenship in 2021 along with the ability to represent France. As of early 2022, he was ranked the number two player in the world by the International Chess Federation.

Mobin Kahrazeh

Born in 1993/1994, Mobin Kahrazeh is a boxer. He defected to Austria in February 2019 due to discrimination against his ethnic Baluch and Sunni religious identity. “In the camps of the national team, from the under-20 team to the adult team, they repeatedly insulted my religion, the Sunni religion,” he said.

Kahrazeh also cited the stressful conditions for athletes in Iran, including pressure to lose matches to avoid facing Israelis. “Not only there is no money, not only are there are no facilities, but also, in international competitions, you must always be careful about whom you lose to and whom you win against.”

Hamoon Derafshipur

Born in 1992, Hamoon Derafshipur is an Olympian karate fighter. He defected to Canada in 2019 so that he could train under his wife, Samira Malekipour. “We are both together, so it’s a dream,” he said in 2021. Rules in Iran did not permit his wife to be his coach, although Malekipour was an accomplished martial artist who won a bronze medal in kumite at the 2019 Asian Games.

Derafshipur won a bronze medal for Iran at the 2018 World Karate Championships. After leaving Iran, he made the 2020 IOC Refugee Olympic Team.

Dina Pouryounes

Born in 1992, Dina Pouryounnes is a taekwondo fighter. She fled to the Netherlands in 2015 and used taekwondo to “rebuild her mental and physical health,” according to a profile of her published by the IOC.

She won her first international competition at the 2015 Polish Open while still living in a facility for asylum seekers. From 2015 to 2021, she won 34 medals at various competitions. In 2021, she competed as part of the refugee team at the Summer Olympics in Tokyo.

Saied Fazoula

Born in 1992, Saied Fazoula is a canoeist. He defected to Germany in 2015 after authorities accused him of converting to Christianity, a punishable offense in Iran. In 2015, during the World Canoe Sprint Championships in Italy, he uploaded a photo of himself in front of the Milan Cathedral to social media. Upon his return to Iran, he said that authorities detained him for two days and threatened the death penalty.

Fazoula then fled Iran and eventually settled in Germany. “If there is one thing I always tell myself, it’s this,” Fazloula told Deutsche Welle in June. “I just have to believe that I will manage, no matter what it is.” In 2021, he competed for the refugee team at the Summer Olympics in Tokyo in the 1000-meter race but did not medal.

Vahid Sarlak

Born in 1981, Vahid Sarlak is a judoka. He defected to Germany in 2010. He claimed that he was forced to throw at least two matches to avoid facing Israeli opponents during his 14-year career with Iran’s judo team. At the 2005 World Championships in Cairo, he was told to lose in the bronze medal match. “It was the worst day of my life,” he told CNN more than a decade later. “A hole opened inside of me and that hole is still open.”

Mahdi Jafargholizadeh

Karate champion Mahdi Jafargholizadeh, a critic of the government, hired a smuggler to take him to Canada in 2004. But he was arrested at the airport and accused of planning to spy for Israel. He claimed that he was tortured, interrogated and pressed to confess to crimes during six months of detention before he was released in 2005 and told there had been a mistake.

Jafargholizadeh was allowed to resume competing in karate tournaments and won the gold and silver medals at the 2005 and 2007 Asian championships. In 2008, however, the president of the Karate Federation – who Jafargholizadeh said had served in the intelligence services – warned that he would not be on the national team another year. The athlete later alleged that former members of the Revolutionary Guards and representatives of the Ministry of Intelligence have headed the karate, taekwondo and judo federations, adding to the securitization of martial arts in Iran.

In 2008, Jafargholizadeh deserted Iran’s national team during a trip to Germany and sought asylum in Finland, where he coached the national team from 2012 to 2014. In 2020, while coaching Malta’s national team, he condemned Iran’s execution of Navid Afkari. “As an athlete, I wholeheartedly support boycotting the Islamic Republic from sporting events of all age categories,” Jafargholizadeh said in a video for United for Navid.

Other athletes who have gone into exile included:

- Shiva Amini, a soccer player who sought asylum in Switzerland in 2017 after facing harassment for playing without a hijab while abroad

- Amir Assadollahzadeh, a world-class powerlifter who sought asylum in Norway in November 2021 after being pressured to wear a shirt with the image of General Qassem Soleimani, the Qods Force commander killed by the United States in 2020

- Mohammad Hassan Ebrahimi, a member of the national fencing team who defected to France in 2010

- Soheila Farhani, a volleyball player and referee who moved to the United States in 2015 for fear of punishment for being lesbian

- Farnaz Koohshekaf, a roller speed skater who moved to Austria in 2015 after she and other female athletes were blocked from competing abroad

- Javad Mahjoub, a judoka who fled to Canada after competing in the 2018 Grand Prix

- Sardar Pashaei, a wrestling world champion and coach of the national Greco-Roman wrestling team, fled to the United States in 2009

Tess Rosenberg, a research analyst at the U.S. Institute of Peace, and Garrett Nada, the managing editor of The Iran Primer, assembled this report.