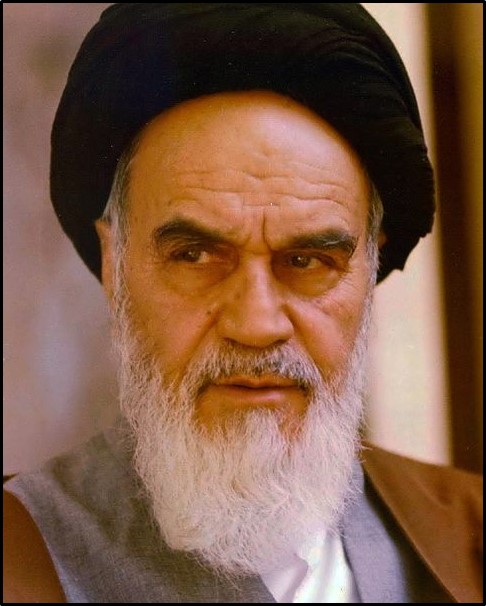

Ebrahim Raisi, winner of Iran’s 2021 presidential election, was a pivotal player in the mass execution of thousands of political prisoners in 1988. At 27, Raisi was the youngest of four members named to the so-called Death Committee for Tehran after the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, issued a fatwa at the end of the eight-year war with Iraq. In July 1988, he decreed that all prisoners steadfast in their support for the opposition and “waging war on God” were “condemned to execution.” He reportedly issued a second or related fatwa focusing on members of communist and leftist parties as well as people charged with apostasy.

The Tehran committee, one of several operating in at least 32 cities throughout the country, selected the prisoners, sometimes by a vote. The Tehran committee did not sign off on all the executions carried out nationwide. Between 4,000 and 5,000 political prisoners were executed countrywide, according to human rights groups. They were often denied due process. Many were serving defined jail sentences, and some of those executed were already due to be released. “The decisions about which prisoners were to be executed and which spared were arbitrary in the extreme,” Amnesty International reported in December 1990.

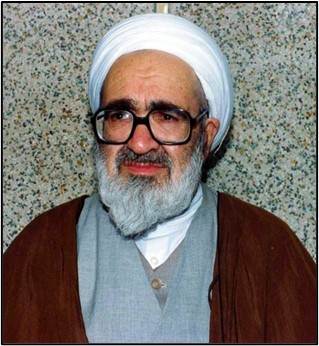

The massacre had a profound impact on Iranian politics. Grand Ayatollah Ali Montazeri, the heir apparent to Khomeini and a long-time disciple, condemned the executions as they were unfolding. In a meeting with the Tehran committee, he reportedly said, “I believe that the biggest crime in the history of the Islamic Republic, which will be condemned by history, happened by your hands,” he told them. “Fighting against ideology with killing is totally wrong.” Friction with Khomeini over the massacre and political persecution eventually forced Montazeri to resign, under pressure, in March 1989. Khomeini died less than 10 weeks later, without naming an alternative.

Iranian officials acknowledged the executions but downplayed the scale. In February 1989, President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani claimed that “less than 1,000” were executed. Other officials argued that the fatwa was necessary to defend against an existential threat. “We're proud to have carried out God's order,” Mostafa Pourmohammadi, another member of the Tehran Death Committee, said in 2016.

Raisi has defended his actions. “If a judge, a prosecutor has defended the security of the people, he should be praised,” he told reporters about the massacre at his first press conference as president-elect on June 21, 2021. The United Nations called for an investigation into Raisi’s role shortly after his election. “I think it is time and it's very important now that Mr. Raisi is the president (-elect) that we start investigating what happened in 1988 and the role of individuals,” Javaid Rehman, the U.N. investigator on human rights in Iran, said on June 29.

Events of 1988

Khomeini’s first fatwa established three-men committees in each province, according to Amnesty. Each included a Sharia (Islamic law) judge, an intelligence ministry official, and the province’s prosecutor general or his deputy. In Tehran, Khomeini’s fatwa specifically named Hossein Ali Nayyeri, a Sharia judge, and Morteza Eshraghi, Tehran’s prosecutor general. Mostafa Pourmohammadi was later appointed from the intelligence ministry. Raisi served as Eshraghi’s deputy and became a de facto member of the committee.

The Tehran “Death Committee” – as it was informally dubbed – interrogated inmates in Evin and Gohardasht prisons about their political and religious beliefs, Amnesty International reported in December 1990. The committee specifically targeted members of the People’s Mujahedeen of Iran (MEK, also known as the PMOI), a Marxist and Islamic faction that participated in the revolution but fell out with Khomeini over a new constitution. In the early 1980s, the MEK was linked to bombings that killed dozens of senior Iranian officials, including a president, a prime minister, the judiciary chief, and an army commander. Many MEK members either went underground or fled to Europe or Iraq, where they supported President Saddam Hussein’s war effort. Even after the war ended in 1988, MEK fighters launched Operation Eternal Light, a cross-border assault from Iraq aimed at inciting a popular uprising in Iran. It failed.

Related Material: The Mujahedeen-e Khalq Controversy

Khomeini’s fatwa instructed the committees, “Even though a unanimous decision is better, the view of a majority of the three must prevail…It is naive to show mercy to those who wage war on God. The decisive way in which Islam treats the enemies of God is among the unquestionable tenets of the Islamic regime.”

During the Death Committee’s investigations, prisoners who admitting affiliation with the MEK were executed. Those who called the MEK “monafeqin” – a derogatory term meaning “hypocrites”- were reportedly spared. According to human rights groups, the interrogators then asked a second set of questions, including whether prisoners would condemn the MEK on television or were willing to clear minefields from the war. Those who refused to answer or answered incorrectly were executed.

Khomeini allegedly issued a second fatwa targeting secular, leftist and communist prisoners, according to Montazeri. It criminalized apostasy, including being born a Muslim but no longer believing in Allah or converting to another religion. No text of the fatwa has ever been published, but leftist prisoners said that they were asked if they believed in God, if they prayed, and if they renounced atheism. Between 300 and 500 prisoners - at least 100 of whom were members of the communist Tudeh party – were executed under Khomeini’s second fatwa, the Center for Human Rights in Iran reported in 2016.

During the committee’s deliberations, Eshraghi “intervened favorably on behalf of several prisoners from families descended from the prophet,” the U.S.-based Abdorrahman Boroumand Center for Human Rights in Iran reported in April 2011. Pourmohammadi was often “invariably holding out for execution,” it said.

The executions triggered fierce internal debates, even among conservatives. Montazeri criticized the system as inhumane. “On what criteria are you now executing people who have not been sentenced to death? he asked the intelligence minister, the prosecutor general and the chief justice in a letter on August 15, 1988. At the time, Montazeri estimated that between 2,800 and 3,800 people had been executed but admitted that he could not recall the exact number. “The political executions took place in many prisons in all parts of Iran, often far from where the armed [MEK] incursion took place,” he wrote. The number of executions in Ahvaz, the capital of southwest Khuzestan province and home to Iran’s restive Arab minority, were even higher than in Tehran, he claimed.

Raisi’s Role

Raisi’s specific responsibilities on the committee are not widely documented. As deputy prosecutor general, Raisi replaced Eshraghi when the prosecutor general was unable to attend meetings or otherwise fulfill his responsibilities, the Boroumand Center reported. He oversaw issues related to family visitation of prisoners and may have participated in interrogations.

During the 1988 meeting between Montazeri and the committee, its members defended their actions, according to an audio recording released by Montazeri’s son in 2016. “I want to assure you that if it were another group, the number of killing would have been three times greater in Tehran,” Nayyeri said. Raisi said little in the meeting; he mainly answered Montazeri’s questions on family visitation rights. But a voice that sounds like Raisi’s can be heard after Montazeri demands that the panel pause executions during the Islamic holy month of Moharram. “Okay, we will obey,” the voice says.

Related Material: Raisi: Record on Crackdown & Human Rights

Raisi’s personal role was largely overlooked until the publication of Montazeri’s audio file in 2016. It triggered an outcry during Raisi’s first presidential run in 2017. President Hassan Rouhani, who was running against Raisi for reelection, criticized him as among those “whose main decisions have only been executions and imprisonments over the past 38 years.” Ahmad Montazeri, the son of the grand ayatollah called Raisi’s candidacy an “insult to the Iranian people,” while Ali Motahari, a maverick conservative lawmaker, called for an investigation into the mass killings.

In May 2018, Raisi broke his silence during a lecture at Ferdowsi University. He noted that he was “not the head of the court” in 1988 and therefore not responsible for the sentences. He praised Khomeini as a “national hero” who fought against “hypocrisy.” Raisi again defended his role after winning the presidency in June 2021. “I am proud to have defended human rights in every position I have held so far,” he told reporters in his first press conference as president-elect.

The members of the Tehran Death Committee never faced professional consequences nor expressed regret for their actions. All four members went on to serve in higher office, but none rose as high as Raisi.

- Morteza Eshraghi, the prosecutor general, served as a judge on the supreme court from 1989 to 1998.

- Hossein Ali Nayyeri, the Sharia judge, served as deputy chief justice of Iran’s supreme court from 1989 to 2013. He has served as the head of Iran’s disciplinary court for judges since 2013.

- Mostafa Pourmohammadi, the intelligence official, served as Interior Minister under President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad from 2005 to 2008 and Justice Minister under President Rouhani from 2013 to 2017.

- Ebrahim Raisi, the deputy prosecutor general, served as prosecutor general of Tehran between 1989 and 1994. He was head of the General Inspection Organization, which is charged with investigating corruption and financial misdeeds, from 1994 to 2004. He was named first deputy head of the judiciary from 2004 to 2014. In 2006, Raisi was elected to the Assembly of Experts, which is charged with appointing and overseeing the supreme leader. He was Iran’s prosecutor general from 2014 to 2016. He served as judiciary chief from 2017 to 2021 before his election as president in June 2021.

International Response

For more than three decades, the massacre has colored the outside world’s perceptions of the Islamic Republic. Human rights organizations and Iranian opposition groups have long demanded a full investigation by the U.N. Human Rights Council or the International Criminal Court in The Hague into the role of all four members of the Tehran committee.

In March 2019, the United States condemned Raisi’s appointment as judiciary chief and highlighted his role in the Tehran Death Committee. “Ebrahim [Raisi], involved in mass executions of political prisoners, was chosen to lead #Iran’s judiciary,” tweeted Robert Palladino, the deputy State Department spokesperson. “What a disgrace!” In November 2019, the Trump administration sanctioned Raisi "for being a person appointed to a position as a state official of Iran by the Supreme Leader of Iran.” The Treasury also noted Raisi's involvement in the Death Committee and the crackdown on protesters after the disputed 2009 presidential election. The legal authority to sanction Raisi was covered by President Donald Trump’s executive order 13876, which targeted anyone who acted for or on behalf of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Sanctions issued under President Barack Obama authorized by Executive Order 13553, which designated Iranian officials responsible for or complicit in serious human rights abuses, did not directly identify Raisi. If Trump’s executive order were to be rescinded, the sanctions on Raisi would either also be lifted or would need to be reimposed under a different legal authority.

Human rights advocates renewed calls for a credible international investigation after Raisi’s election in 2021. Agnès Callamard, secretary general of Amnesty International, demanded that Raisi be investigated for “crimes against humanity” by the U.N. Human Rights Council. “The circumstances surrounding the fate of the victims and the whereabouts of their bodies are, to this day, systematically concealed by the Iranian authorities,” Callamard said on June 19.

Related Material: Raisi: Human Rights Groups Condemn

Western governments also expressed concern about Raisi’s record. “It is concerning that the elected president has until now not clarified his own past or distanced himself clearly from human rights abuses,” Bärbel Kofler, Germany’s human rights commissioner, tweeted on June 20. White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki warned on June 21 that Raisi “will be accountable for gross violations of human rights on his watch going forward.” But the State Department and National Security Council also made clear that Raisi’s election would not affect negotiations over the U.S. and Iran returning to compliance with the 2015 nuclear deal.

Related Material: Raisi: U.S. & World Reaction

Since 1988, human rights groups, Western governments and the United Nations have repeatedly condemned the massacre and called for investigations into Raisi’s role. The following is a list of reports by major organizations, with excerpts and links to their full reports.

Reports

Amnesty International

In mid-1988 the pattern of political executions changed dramatically from piecemeal reports of executions to a massive wave of killings which took place over several months. Even now, two years after these events, it is still not clear how many people died during the six-month period from July 1988 to January 1989. Amnesty International has recorded the names of over 2,000 political prisoners reportedly executed during this period. Iranian opposition groups, such as the PMOI (People’s Mujahedeen of Iran), have suggested that the total was much higher. Speaking on French television in February 1989, Hojatoleslam Rafsanjani is reported to have said that “the number of political prisoners executed in the past few months was less than 1,000.”

The political executions took place in many prisons in all parts of Iran, often far from where the armed incursion took place. Most of the executions were of political prisoners, including an unknown number of prisoners of conscience, who had already served a number of years in prison. They could have played no part in the armed incursion, and they were in no position to take part in spying or terrorist activities. Many of the dead had been tried and sentenced to prison terms during the early 1980s, many for non-violent offences such as distributing newspapers and leaflets, taking part in demonstrations or collecting funds for prisoners' families. Many of the dead had been students in their teens or early twenties at the time of their arrest. The majority of those killed were supporters of the PMOI, but hundreds of members and supporters of other political groups, including various factions of the PFOI (People's Fedayeen Organization of Iran, a left wing group), the Tudeh Party, the KDPI (the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Iran, an ethnic separatist group), Rah-e Kargar and others, were also among the execution victims.

The first sign that something was happening in the prisons came in July 1988 when family visits to political prisoners were suspended. This was the beginning of months of uncertainty and anguish for prisoners' relatives as rumors began to spread that mass executions of political prisoners were taking place. No news of the political prisoners was heard for about three months. Relatives would go to prisons on regular visiting days only to be turned away by prison guards. Some brought clothing, medicines or money to the prisons hoping to get a signed receipt from their imprisoned relatives as an indication that they were still alive.

Reports circulated among prisoners' relatives that execution victims were being buried in mass graves. Distraught family members searched the cemeteries for signs of newly dug graves which might contain their relatives' bodies… One woman described to Amnesty International how she had dug up the corpse of an executed man with her bare hands as she searched for her husband's body in Jadeh Khavaran cemetery in Tehran in August 1988 in a part of the cemetery known colloquially as Lanatabad, (the place of the damned), reserved for the bodies of executed political prisoners.

In October and November 1988, the authorities began to inform families of the execution of their relatives. In a few cases prison officials informed relatives of the execution when they went to the prison for a normal family visit. This led to protests by prisoners' relatives who gathered outside prisons, so other methods were devised. The majority of relatives appear to have been informed by telephone that they should go to an Islamic Revolutionary Committee office to receive news about their imprisoned relatives. There they were informed of the execution and required to sign undertakings that they would not hold a funeral or any other mourning ceremony. Family members were not informed where their relatives were buried, and even if they managed to find out they were not permitted to erect a gravestone.

Prisoners in Gohardasht Prison in Karaj appear to have had a much clearer picture of the events which were taking place. Former prisoners have described to Amnesty International how a commission made up of representatives from the Islamic Revolutionary Courts, the Revolutionary Prosecutor's Office and the Ministry of Intelligence began to subject all political prisoners to a form of retrial in July 1988.

These ‘retrials’ bore little resemblance to judicial proceedings aimed at establishing the guilt or innocence of a defendant with regard to a recognized criminal offence under the law. Instead, they appear to have been formalized interrogation sessions designed to discover the political views of the prisoner in order that prisoners who did not “repent” should be executed -- the punishment of all those who continued to oppose the government.”

The majority of prisoners were reportedly unwilling to give the desired responses and were consequently sent for execution. Some 200 out of 300 PMOI prisoners in Sections 3 and 4 of Gohardasht Prison were killed following this type of interrogation. The interrogations were reportedly conducted in such a way as to trick prisoners into making statements revealing their opposition to the government.

The prisoners named the interrogators the ‘Death Commission.’ It came to Gohardasht Prison three times a week, arriving by helicopter. The same commission was also reportedly at work in Evin Prison.

At the end of August 1988 the ‘Death Commission’ turned its attention to the prisoners from leftist groups held in Gohardasht Prison. These included supporters of the Tudeh Party, various factions of the PFOI, and others. The interrogations followed a similar pattern, with prisoners being asked if they were prepared to make public statements criticizing the political organization with which they had been associated. The leftist prisoners were also asked about their religious faith. They were asked such questions as: Do you pray? Do you read the Qur'an? Did your father read the Qur'an?

According to another eye-witness account of this period in Gohardasht Prison, the decisions about which prisoners were to be executed and which spared were arbitrary in the extreme. Some prisoners who had been sentenced to death by the commission were spared because prison guards sent prisoners whom they disliked to be executed in their place. There was also a great deal of confusion as prisoners were transferred from different prisons, and from section to section within the prison. As a result of such confusion, prisoners were sometimes executed by mistake.

The same eye-witness estimates that out of 900 PMOI and 600 leftist prisoners in Gohardasht Prison at the beginning of the summer of 1988, 600 PMOI prisoners and 200 leftist prisoners were executed. In Evin Prison, where the execution of prisoners was going on simultaneously, the proportion of executions carried out from the total population of political prisoners was much higher. One reason suggested for this is that in Evin there was no way for prisoners to communicate with each other, so they were unable to prepare answers to questions put to them by the ‘Death Commission’ as prisoners in Gohardasht had done.

Related Material: Amnesty International issued a second report in August 2008. Iran: The 20th anniversary of 1988 "prison massacre"

Related Material: Amnesty International issued a third report in December 2018. Iran: blood-soaked secrets: why Iran's 1988 prison massacres are ongoing crimes against humanity

Abdorrahman Boroumand Center

The Tehran ‘Death Committee’ of Nayyeri, Eshraqi (sometimes replaced by his Deputy, Ebrahim Raisi) and an intelligence official (usually Pourmohammadi) went into immediate operation in both Evin and Gohardasht Prisons. There is evidence that its decision were sometimes taken by majority, with the intelligence official invariably holding out for execution. Eshraqi was, reportedly, the member who intervened favorably on behalf of several prisoners from families descended from the prophet. It may not have been an altogether comfortable task for Tehran’s Revolutionary Prosecutor, only a fortnight after he had been holding press conferences about the need to crack down on drug dealers and commenting that his office merely ‘continued to investigate’ acts by the mini-groups. Some religious judges appointed to Death Committees in the provinces had reservations, and contacted Ayatollah Montazeri for guidance – this was the first he knew about the fatwa, which concluded with this chilling exhortation to cruelty:

“It is naive to show mercy to Moharebs (“those who wage war on God”). The decisiveness of Islam before the enemies of God is among the unquestionable tenets of the Islamic regime. I hope that you satisfy almighty God with your revolutionary rage and rancor against the enemies of Islam. The gentlemen who are responsible for making the decisions must not hesitate, nor show any doubt or concerns with detail. They must try to be “most ferocious against infidels.” To hesitate in the judicial process of revolutionary Islam is to ignore the pure and holy blood of the martyrs.

This was an order from the highest authority, and its existence has not been denied, although the regime has not made any direct statement on the subject. During the 2009 election campaign Mir Hossein Mousavi replied to questions about his involvement in the massacres with a standard response that as he was the head of the civil administration he had nothing to do with them. Another opposition figure, ex-President Khatami said that he and his fellow reformists should not have remained silent about this “tragedy” but was not forthcoming further.

However, some corroboration was accidentally provided in 2004 by the Secretary of the Islamic Motalefeh Party, in an interview with a student newspaper about Lajevardi, the brutal prosecutor of Evin, who had been “martyred” (i.e. assassinated) on the 10th anniversary of the massacres by the Mujahedeen. He admitted that Lajevardi’s hardline conduct in the prisons had been opposed by Montazeri, but the former had been vindicated by the Supreme Leader: “With his decree regarding the Monafeqin prisoners after the Mersad operation the Imam demonstrated his displeasure at the lax attitude of the judiciary towards the Monafeqin and the pardon policy it was implementing... of course the content of this decree is of a sensitive nature and it cannot be discussed here.”

There could be no going back, and the very next day – 29 July – the implementation measures began. The prisons were put on lockdown, with all family visits cancelled and radios and televisions removed from wards. The Death Committee hearings commenced.

Center for Human Rights in Iran

The exact number of political prisoners who have been executed in Iran since 1979 is unknown; if any records exist, the government has concealed them. But an investigation by the British Broadcasting Corporation Persian (BBC Persian) from 2013 estimated that—based on interviews with human rights groups and the families of the victims—close to 11,000 people were executed between 1981 and 1985 and more than 4,000 in the summer of 1988.

Montazeri, who was Khomeini’s deputy before being sidelined for opposing the executions, provided some detail about the 1988 prison massacre in his memoir.

“After the MEK, with Iraq’s backing, launched the Mersad Operation against the Islamic Republic of Iran [in July 1988 during the Iran-Iraq war], a number of them were killed and some were taken prisoner. Presumably, they were put on trial. But that is not the issue,” Montazeri wrote. “What prompted me to write a letter at the time was the fact that some individuals had decided to wipe out the MEK and be done with them. They got the imam [Khomeini] to issue an order to deal with their members in prison. A three-member tribunal was formed and if two of the judges decided that such and such prisoner was still adamant on his views, she/he would be executed… The imam’s order does not have a date on it. But it was written on a Thursday and on the following Saturday it was given to me by a judge who was very upset. I studied the order. It had a very angry tone in response to the MEK’s Mersad Operation. It was said that the order was in Ahmad [Khomeini’s] handwriting.” [Ahmad Khomeini was the son of the supreme leader.]

Montazeri added: ‘Finally, they cancelled prison visitations, and based on what I heard from the officials in charge, [Khomeini’s] order resulted in the execution of 2,800 or 3,800 men and women prisoners, but I’m not certain [of the number]. There were even some prisoners who prayed and fasted and were asked to repent and they would be insulted and refuse and then they would be judged for remaining adamant on their views and executed. In Qom, one of the judicial officials came to me and complained about the Intelligence Ministry representative in the city who wanted to quickly kill [MEK prisoners] and get rid of them.’

Human Rights Watch

In 1988, Mustafa Pourmohammadi represented the Ministry of Information on a three-person committee that ordered the execution of thousands of political prisoners. These systematic killings constitute a crime against humanity under international human rights law. In his role as a deputy and designated acting minister of information in 1998, Pourmohammadi is also suspected of ordering the murders of several dissident writers and intellectuals by agents of the Ministry of Information. In addition, while Pourmohammadi headed the foreign intelligence section of the Ministry of Information, government agents carried out assassinations of numerous opposition figures abroad. Mustafa Pour-Mohammadi also served as prosecutor of the Revolutionary Court (1979- 1986) and prosecutor of the Armed Forces Revolutionary Court in the western regions (1986).”

In 1988, the Iranian government summarily and extrajudicially executed thousands of political prisoners held in Iranian jails. The government has never acknowledged these executions, or provided any information as to how many prisoners were killed. The majority of those executed were serving prison sentences for their political activities after unfair trials in revolutionary courts. Those who had been sentenced, however, had not been sentenced to death. The deliberate and systematic manner in which these extrajudicial executions took place constitutes a crime against humanity under international law.

On July 18, 1988, Iran accepted the United Nations Security Council Resolution 598, calling for a cease-fire in the eight-year war between Iran and Iraq. On July 24, the largest Iranian armed opposition group, the Mujahedeen-e Khalq Organization, based in Iraq since 1986, launched an incursion into Iran in an attempt to topple the government. Although this offensive was easily repelled by Iranian forces, it provided a pretext for the authorities to physically eliminate many political opponents then in prison, including many [MEK] members captured and sentenced years earlier.

In the absence of any official acknowledgement of the 1988 prison massacre, the most credible account of these events comes from the memoirs of Ayatollah Hussein Ali Montazeri, who was at the time one of the highest-ranking government officials in Iran and the designated successor of Ayatollah Khomeini, then the Supreme Leader.

Ayatollah Montazeri, citing officials in charge of carrying out the executions, puts the number of executed prisoners between 2,800 and 3,800, but he acknowledges that his recollection is not exact. Iranian activists have published the names of 4,481 executed prisoners. As long as the government refuses to announce a complete list of those executed or even to acknowledge that these executions took place, the extent of this massacre remains unknown.

State Department

Exiles and human rights monitors allege that many of those executed for criminal offenses, such as narcotics trafficking, are actually political dissidents. Supporters of outlawed political organizations, such as the Mujahedeen-e Khalq organization, are believed to make up a large number of those executed each year.

There were reports that some persons have been held in prison for years and charged with sympathizing with outlawed groups, such as the domestic terrorist organization, the Mujahedeen-e- Khalq.

On September 8, a revolutionary court sentenced Misagh Yazdan-Nejad, a 23-year-old university student, to 14 years in Gohardasht Prison in Karaj for participating in a ceremony in 2007 to commemorate those killed in the 1988 mass executions of political prisoners reportedly associated with the MEK. The government had previously executed three of Yazdan-Nejad's uncles and imprisoned both his parents on political grounds.

Impunity for past unlawful killings remained a serious problem. On August 8, several international human rights groups, including the international NGO Human Rights Watch (HRW), issued a joint statement protesting President Rouhani’s nomination of Mostafa Pourmohammadi for the post of justice minister, citing documentation implying his involvement in the extrajudicial executions of thousands of political dissidents in 1988 and in the killings of several prominent dissident intellectuals in 1998. On August 15, parliament confirmed Pourmohammadi’s appointment.

Impunity for past unlawful killings remained a serious problem. Human rights groups, including Human Rights Watch, cited documentation implying that Justice Minister Mostafa Pourmohammadi was involved in the extrajudicial executions of thousands of political dissidents in 1988 and in the killings of several prominent dissident intellectuals in 1998.

Local media reported on the November 27 sentencing of prominent cleric, Hojjatoleslam Ahmad Montazeri, to 21 years in prison by the Qom branch of the Special Clerical Court for “endangering national security” and “leaking secrets of the Islamic system” after he posted audio recordings of his father, the late dissident cleric, Hossein Ali Montazeri, condemning the 1988 mass execution of political prisoners.

Human rights groups highlighted the case of children’s rights activist Atena Daemi, serving a seven-year sentence for meeting with the families of political prisoners, criticizing the government on Facebook, and condemning the 1988 mass executions of prisoners in the country.

Treasury

Today, OFAC designated Ebrahim Raisi, the head of Iran’s Judiciary, who was appointed by the Supreme Leader in March 2019…. According to a United Nations report, Iran’s Judiciary sanctioned the execution of seven child offenders last year, and two so far in 2019, despite human rights law prohibitions against the death penalty for anyone under age 18. There are at least 90 child offenders currently on death row in Iran. In addition, between September 2018 and July 2019, at least eight prominent lawyers were arrested for defending political prisoners and human rights defenders, many of whom have received lengthy sentences by Iran’s Judiciary.

Prior to Raisi’s appointment as head of the Judiciary, he served as prosecutor general of Tehran between 1989 and 1994, first deputy head of the judiciary from 2004 to 2014, and Iran’s prosecutor general from 2014 to 2016. Raisi was involved in the regime’s brutal crackdown on Iran’s Green Movement protests that followed the chaotic and disorderly 2009 election. Previously, as deputy prosecutor general of Tehran, Raisi participated in a so-called ‘death commission’ that ordered the extrajudicial executions of thousands of political prisoners in 1988.

United Nations

Between July and September 1988, the Iranian authorities forcibly disappeared and extrajudicially executed thousands of imprisoned political dissidents affiliated with political opposition groups in 32 cities in secret and discarded their bodies, mostly in unmarked mass graves.”

The mass killings of prisoners took place in 16 cities across Iran, in particular in Ahvaz in Khuzestan province, Dezful in Khuzestan province, Esfahan in Esfahan province, Hamedan in Hamedan province, Khorramabad in Lorestan province, Lahijan in Gilan province, Mashhad in Razavi Khorasan province, Rasht in Gilan province, Sanandaj in Kurdistan province, Sari in Mazandaran province, Semnan in Semnan province, Shiraz in Fars province, Tabriz in East Azerbaijan province and Urumieh in West Azerbaijan province, Zahedan in Sistan and Baluchistan province, and Zanjan in Zanjan province.

Additionally, prisoners were targeted in at least 16 other cities across the country: Arak in Arak province, Ardabil in Ardabil province, Babol, Behshahr and Ghaemshahr in Mazandaran province, Behbahan in Khuzestan province, Bushehr in Bushehr province, Gorgan in Golestan province, Ilam in Ilam province, Karaj in Alborz province, Saqqez in Kurdistan province, Kermanshah in Kermanshah province, Kerman in Kerman province, Roudsar in Gilan province, Tehran in Tehran province and Qazvin in Qazvin province.

While it is believed that all of the individuals who disappeared during this period have been killed, individual information has not been provided to families about the fate and whereabouts of their relatives, the circumstances leading to their execution and the location of their remains. This continues to cause extreme anguish to the families of the victims, some of whom still disbelieve that their relatives are dead.

Regarding the location of their loved one’s remains, families either remained uninformed about the location or learnt about their burial in suspected or known mass grave sites through informal contact with prison guards and officials, cemetery workers or locals. It is also alleged that many prisoners were transferred to different locations prior to their enforced disappearance and execution.

For some cities such as Ahvaz, Ardabil, Ilam, Mashhad and Roudsar, the authorities ultimately told some families verbally that their loved ones were buried in mass graves and revealed their locations. However, publicly and officially, the authorities have never acknowledged these mass grave sites, which have been subjected to desecration and destruction. This includes by bulldozing them and then constructing new burial plots, buildings or roads over them.

Regarding seven other cities, specifically Bandar Anzali, Esfahan, Hamedan, Masjed Soleiman, Shiraz, Semnan, and Tehran, the authorities gave a few families the location of individual graves and allowed them to install headstones, but many fear that the authorities may have deceived them and that some of these graves may be empty.

In some cities such as Ahvaz, Karaj, Rasht, Tehran and Mashhad, more than one mass grave site was reported. It is likely that the real number of mass graves across the country which resulted from the alleged mass secret extrajudicial executions of 1988 is far higher. The Iranian authorities have also excluded the names of the overwhelming majority of the victims from publicly available burial registers to conceal the location of the remains.