Tensions between the United States and Iran created a political crisis in Baghdad in September after months of attacks on U.S. personnel and facilities by Iraqi militias armed, trained and aided by Tehran. The militias targeted U.S. bases, supply convoys and diplomatic facilities almost daily in September. “We have had more indirect fire attacks around and against our bases the first half of this year than we did the first half of last year,” General Kenneth McKenzie Jr., the head of U.S. Central Command, told NBC News on September 10. The escalation follows the U.S. assassination in January of General Qassem Soleimani, the head of Iran’s elite Qods Force, and Abu Mahdi al Muhandis, chief of Iraq’s Kataib Hezbollah militia and the deputy head of Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF). The PMF is an umbrella for some 60 militias that operate in separate brigades.

The crisis reached a peak on September 20 when Washington warned Baghdad that it would soon close its fortified embassy in Baghdad unless Iraq stopped the militia attacks and brought the diverse PMF factions under state control. Secretary of State Pompeo’s warning, given in separate phone calls with President Barham Salih and Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al Kadhimi, was reportedly a surprise to Iraqi officials. “We hope the American administration will reconsider it,” Ahmed Mulla Talal, a spokesman for Kadhimi said on September 27. “There are outlaw groups that try to shake this relationship, and closing the embassy would send a negative message to them.”

The crisis reached a peak on September 20 when Washington warned Baghdad that it would soon close its fortified embassy in Baghdad unless Iraq stopped the militia attacks and brought the diverse PMF factions under state control. Secretary of State Pompeo’s warning, given in separate phone calls with President Barham Salih and Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al Kadhimi, was reportedly a surprise to Iraqi officials. “We hope the American administration will reconsider it,” Ahmed Mulla Talal, a spokesman for Kadhimi said on September 27. “There are outlaw groups that try to shake this relationship, and closing the embassy would send a negative message to them.”

Some U.S. media reported that the militias were plotting a direct attack on U.S. diplomats. More than 3,000 troops are deployed in Iraq; the U.S. Embassy, which has hundreds of diplomats and employees, is one of the biggest in the world.

Pompeo’s ultimatum came just four weeks after Prime Minister Kadhimi’s first visit to Washington signaled improved relations. The U.S.-Iraq relationship “is better than ever before,” President Donald Trump said during his Oval Office meeting with Kadhimi on August 20.

Kadhimi later acknowledged that U.S. officials were worried about Iraq’s militias. The new government, formed in May, had started to confront the broader “militarization” of Iraqi society, Kadhimi told journalists after seeing Trump. “Any weapons outside government control will not be tolerated.” But Iraqi security forces also need to be strengthened to contain the array of militias—Sunni, Shiite, Kurdish and Christian—that have proliferated since the 2003 U.S. invasion toppled President Saddam Hussein. “I have a paper sword. I need to turn it into a wooden sword, then eventually a metal sword,” he said. “I cannot afford to go to a confrontation while my tools are insufficient.”

Iran has emerged as the most influential foreign player in Iraq – politically, militarily and economically – since U.S.-led forces toppled Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003. Predominantly Shiite Iran took advantage of deep cultural and religious ties with Iraq’s Shiite majority – and a 900-mile border – to spread its influence. Since 2003, successive Iraqi governments have been caught in the middle of the U.S.-Iran rivalry. “It is a bitter fact that sometimes both countries were deciding who will be the next prime minister” in Iraq, Foreign Minister Hussein said on August 21. “The conflict between Washington and Tehran reflects itself inside Iraq... But we need both of you. One of them is our neighbor and a big power in the region. And the other one is our ally and a big power in the world.”

Iran also fostered the creation of dozens of predominantly Shiite militias that became pivotal in countering ISIS in 2014 and later in menacing U.S. troops. On December 27, 2019, Kataib Hezbollah launched rockets at the K1 military base near Kirkuk, which housed U.S. military service members and Iraqi personnel. The attack killed a U.S. civilian contractor and wounded four U.S. service members and two Iraqis. The death of the contractor led to an escalation in U.S.-Iran tensions resulting in the U.S. killing of Soleimani and Muhandis. Iran retaliated by firing more than a dozen missiles at two Iraqi military bases housing U.S. troops.

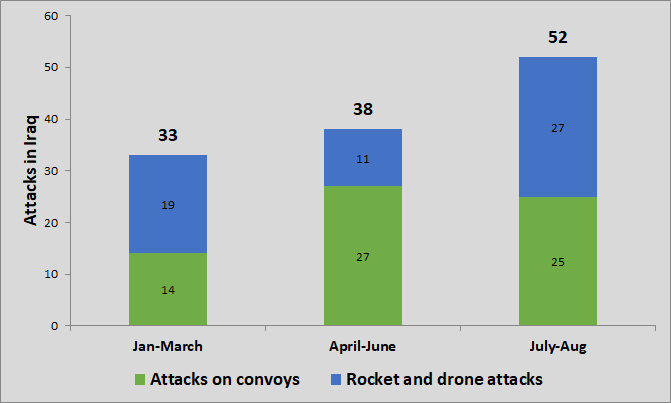

From January to September 2020, Iraqi militias carried out more than 120 attacks, according to Michael Knights at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. They included:

- 66 attacks on truck convoys carrying supplies for U.S. diplomatic facilities or U.S.-led coalition forces

- 57 rocket and drone attacks on other U.S. targets, including the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad

Source: Knights, Washington Institute for Near East Policy

The U.S.-led coalition “acknowledges an increase in low level attacks this summer against the Iraqi Security Forces by outlaw armed factions,” according to a statement by U.S. Central Command Combined Joint Task Force – Operation Inherent Resolve. “These outlaw groups are attacking Iraqi contracted civilian logistics convoys who are transporting logistical support of the ISF and Coalition in the fight against Daesh [ISIS].” U.S. Central Command uses the term “outlaw groups” to refer to the full range of militias operating in Iraq.

The attacks have been “steady harassment” but do not pose a serious threat to U.S. military forces, according to Knights. But the U.S. embassy in Baghdad was highly vulnerable to attack or hostage-taking in the run-up to the U.S. election, a “high-threat period,” he said. Kataib Hezbollah supporters stormed the U.S. Embassy in December 2019, one of the incidents that triggered the assassination of Soleimani and started the ongoing cycle.

Iraq reacted with major diplomatic and military initiatives. On September 24, Falih al Fayadh, the chairman of the PMF and a former Iraqi national security adviser, condemned attacks carried out in the name of the group. Attacks on diplomatic missions “undermine the state and its authority,” the Fatah Alliance, a parliamentary block of pro-Iran parties, said in a statement. Fayadh also fired two leaders of separate PMF factions—Sayyed Hamed al Jazaeri of Saraya al Khorasani (the 18th PMF Brigade) and Waad Qaddo of Shabak in the Nineveh Plains (the 30th PMF Brigade).

Kadhimi also dispatched Foreign Minister Fuad Hussein to Iran to help deescalate tensions. Iranian President Hassan Rouhani told Hussein that the presence of U.S. forces in the region was “detrimental to regional security and stability.” After two days of talks, Iraq’s foreign ministry said that Iraq and Iran agreed that all Iraqi factions and parties should cooperate with the Baghdad government “to face the crises on Iraq and the region, as conflicts on the Iraqi arena may negatively affect stability in the region.” Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif said that he emphasized the “imperative of protection of diplomatic posts” in his meeting with Hussein.

Pleased to host my friend Iraqi FM @Fuad_Hussein1. Reviewed practical steps to further enhance bilateral cooperation. Discussed US terrorist murder of our hero—General Soleimani—and attacks on Iranian diplomatic premises. Underlined imperative of protection of diplomatic posts. pic.twitter.com/1EYzWPn5J3

— Javad Zarif (@JZarif) September 26, 2020

“Iraq is keen on enforcing the rule of law, the state's monopoly on having weapons, protecting foreign missions, and diplomatic buildings,” Kadhimi told the foreign diplomatic corps in Baghdad on September 30. “Those who carry out attacks on foreign missions are seeking to destabilize Iraq and sabotage its regional and international relations.”

On October 10, a group of militias, the “Iraqi Resistance Coordination Commission,” released a statement saying that they would suspend attacks on U.S. targets if the Iraqi government presents a timetable for the departure of U.S. troops. The conditional ceasefire “includes all factions of the (anti-U.S.) resistance, including those who have been targeting U.S. forces,” Kataib Hezbollah spokesman Mohammed Mohi told Reuters. He urged the government to implement a non-binding resolution passed by parliament in January to expel foreign troops from Iraq. If U.S. troops do not leave, the militias “will use all the weapons at their disposal,” Mohi warned.

On September 10, McKenzie praised Iraq for doing a “pretty good job” of protecting U.S. forces. “They've been responsive when people have fired rockets at us. They've gone out there to try to find them.” The attacks had not been “particularly lethal,” he said. The Iraqi militias backed by Iran have not been using their “high-end weapon systems. For whatever reason, it may be by design, we don't know, they're just not that successful at hitting anyone. And that's a blessing.”

A second issue between Washington and Baghdad is Iraq’s dependence on Iranian energy. The United States has sanctioned all Iranian oil exports but has been forced to give Iraq short-term waivers because it has no convenient or affordable alternatives. During Kadhimi’s visit to Washington, Iraq’s oil and electricity ministers signed agreements with five U.S. companies, including Chevron Corp and General Electric, to develop Iraq’s energy sector. The deals are worth $8 billion to the American companies. But they may take months or longer to fulfill. “Iraq currently has no choice but to import natural gas and electricity from Iran,” Kadhimi acknowledged on August 20. In late September, the United States extended a sanctions waiver, but for 60 days instead of the 120 days granted in May. In November, the United States extended it again but only for 45 days.

On October 12, Abdolanser Hemmati, the head of Iran’s central bank, reportedly finalized a deal to allow Iran to buy essential goods from Iraq using payments for electricity and natural gas. As of June 2020, Iraq owed Iran at least $800 million for electricity, according to Iranian Energy Minister Reza Ardakanian. In February 2019, Iranian Oil Minister Bijan Zanganeh said that Iraq owed Iran some $2 billion for natural gas purchases.

On October 22, the United States sanctioned Iran’s ambassador to Baghdad, Iraj Masjedi. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo described Masjedi a senior Qods Force general who had helped train and support Iraqi militias for many years. Masjedi “has exploited his diplomatic position to facilitate financial transfers in Iraq for Qods Force,” Pompeo said.

Iran responded with sanctions on top U.S. officials in Iraq, including Ambassador Matthew Tueller, Deputy Chief of Mission Steven Fagin and Consul General in Erbil, the capital of the Kurdish region, Rob Waller. The foreign ministry alleged that the three men were involved in “acts of terror” against Iranian interests, including the U.S. killing of Soleimani.

The following are profiles of militias that have been the most aggressive against U.S. forces, according to Knights. All were part of the PMF, an umbrella group of some 60 old and new militias formed in mid-2014 in response to ISIS’ capture of wide swaths of Iraqi territory.

- Kataib Hezbollah, or the Brigades of the Party of God (PMF Brigade 45, 56 and 57) dates back to 2004, when the Shiite militias began attacks on the U.S.-led coalition. Five small armed groups united to form Kataib Hezbollah in 2007 under the tutelage of Iran, which provided weapons, funding and military advice; some of its fighters trained in Iran. Its fighters were held responsible for attacks on the U.S.-led coalition in Iraq. After the 2011 U.S. withdrawal from Iraq, Kataib Hezbollah dispatched fighters to defend the Assad regime in Syria at the behest of Iran. Kataib Hezbollah joined the PMF 2014. It has been responsible for some of the deadliest attacks on U.S. forces.

- Asaib Ahl al Haq, or League of the Righteous (PMF Brigade 41, 42 and 43, also known as the Khazali Network) was founded in Iraq in 2006. AAH was an off-shoot of Muqtada al Sadr’s Mahdi Army. It was initially equipped, funded and trained by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Qods Force, with support from Lebanese Hezbollah, in Iranian camps. It became one of the largest and most prominent militias in the PMF.

- Harakat Hezbollah al Nujaba (HHN), or Movement of the Party of God’s Nobles (PMF Brigade 12) is an offshoot of AAH and KH. It is an Iraqi group that was originally formed in 2013 to support the Assad regime in Syria. In 2014, its mission expanded to fight ISIS. HHN leaders have publicly acknowledged Iran’s support.

- Kataib Sayyad al Shuhada (KSS), or The Masters of the Martyrs Brigade (PMF Brigade 14) was established in May 2013 to fight alongside the Assad regime in Syria. Similar to HHN, KSS expanded its operations to Iraq after the rise of the Islamic State in 2014. KSS has been supported and funded by the IRGC since its inception.

- Kataib Jund al Imam (KJI), or The Imam's Soldiers' Brigades (PMF Brigade 6) was formed during the uprising against Saddam Hussein’s government in southern Iraq in 1991. It is affiliated with the pro-Iran “Islamic Movement in Iraq.”

- Saraya al Khorasan, or Khorosani Brigades (PMF Brigade 18) dates back to Iran-backed elements in the 1990s. It announced deployments to Syria starting in 2013 and later jointed the fight against ISIS.

- Saraya al Jihad, or the Jihad Brigades (PMF Brigade 17) was established in 2014 soon after ISIS captured Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city. It is affiliated with the Jihad and Development Movement, a political party, and reportedly deployed to Syria to fight for the Assad regime.

Garrett Nada is the managing editor of The Iran Primer at the U.S. Institute of Peace. Follow him on Twitter @GarrettNada.