Garrett Nada

President Hassan Rouhani faces growing pressure from hardliners for trying to improve Iran’s pariah status and, even tepidly, open up Iranian society. In recent weeks, politicians and media critics have lambasted Rouhani in the run-up to the latest nuclear talks between Iran and the world’s six major powers, which began on May 13. “We fundamentally disapprove of this administration” which is made up of “radical reformists,” lawmaker Ruhollah Hosseinian told Arya News on April 23.

President Hassan Rouhani faces growing pressure from hardliners for trying to improve Iran’s pariah status and, even tepidly, open up Iranian society. In recent weeks, politicians and media critics have lambasted Rouhani in the run-up to the latest nuclear talks between Iran and the world’s six major powers, which began on May 13. “We fundamentally disapprove of this administration” which is made up of “radical reformists,” lawmaker Ruhollah Hosseinian told Arya News on April 23.

The president countered with a tough defense of his foreign and domestic policies in a television address on April 29. Rouhani dismissed his critics and said that his government had created an atmosphere in which citizens could actually criticize policies – “even though sometimes [they] make a mountain out of a molehill.”

Hardliners fear that nuclear talks could enhance Rouhani’s leverage on human rights and social issues. The president, who will mark the first anniversary of his election in mid-June, is under fire especially on four fronts.

Nuclear Talks

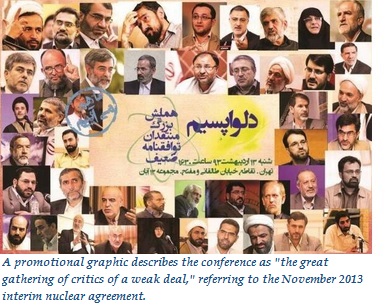

Hardliners have accused the Rouhani administration’s negotiators of caving to Western demands. In the run-up to the mid-May negotiations between Iran and the six major world powers, Rouhani’s critics held a conference entitled “We’re Worried.” The event — advertised as “the great gathering of critics of a weak deal”— was held at the former U.S. Embassy in Tehran on May 3-4. Speakers vowed to retain Iran’s “nuclear rights” and warned the government of President Hassan Rouhani against giving too many concessions. They claimed that Iran’s negotiating team may sacrifice national interests to secure a final deal.

Hardliners have accused the Rouhani administration’s negotiators of caving to Western demands. In the run-up to the mid-May negotiations between Iran and the six major world powers, Rouhani’s critics held a conference entitled “We’re Worried.” The event — advertised as “the great gathering of critics of a weak deal”— was held at the former U.S. Embassy in Tehran on May 3-4. Speakers vowed to retain Iran’s “nuclear rights” and warned the government of President Hassan Rouhani against giving too many concessions. They claimed that Iran’s negotiating team may sacrifice national interests to secure a final deal. More than 100 lawmakers, students, academics and activists attended the event, which was reportedly organized by Basij paramilitary. Officials of former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s administration attended. Participants carried placards which vowed "Nuclear energy is our absolute right" and "Economic reform does not mean political capitulation."

The conference communique included several demands:

•Clear recognition of Iran’s right to enrich uranium

•Continued development of peaceful nuclear activities

•Refusal of additional measures requested by the United Nations beyond the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty

•Imminent removal of financial and banking sanctions

•Release of Iran’s frozen properties

•Transparency on the negotiations and timelines

•Advance approval by parliament and the Supreme National Security Council of any deal with the U.N. nuclear watchdog

The hardliners followed up the conference with a rally after Friday prayers on May 9. Demonstrators calling themselves the “Committee for the Preservation of Iran’s interests” reportedly chanted slogans including “Nuclear development is our absolute right!” and “No Compromise! No surrender! Battle with America!” The group issued a statement accusing the nuclear negotiators of acting with “haste” and lacking expertise.

Internet Censorship

Rouhani campaigned for better access to information and less government oversight. After his June 2013 election, Rouhani warned, “In the age of digital revolution, one cannot live or govern in a quarantine.” But hardliners have sabotaged efforts by his administration to ease web censorship.

Rouhani reversed the decision. “Until the time that we have a replacement for these sites, the government opposes filtering them,” Telecommunications Minister Mahmoud Vaezi told the press.

But Rouhani has failed to unblock Facebook, Twitter and other social media. Last year, Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance Ali Jannati said that social media should be “accessible for everyone” and called for filtering to be reduced. In January, he told Al Jazeera that the judiciary was holding back the new government’s attempts to open up society. He has since been publicly chastised. Prosecutor General Gholamhossein Mohseni Ejehi told the press that Jannati “is not at the level to define the judiciary’s responsibilities.”

Women’s Dress Code

Although he is a cleric, Rouhani has criticized police enforcement of Iran’s strict Islamic dress code, which requires women to cover their head and shoulders. “If there is a need for a warning on the hijab issue, the police should be the last to give it,” he told police academy graduates in October. “Our virtuous women should feel safe and relaxed in the presence of the police,” he added.

But hardliners have fought against relaxation of dress code enforcement. On May 7, some 4,000 men and women reportedly took to Tehran’s streets to protest “bad veiling.” “Preserving public chastity, observing Islamic hijab and moral security are strategic matters which shall not be forgotten under the pretext of economic sanctions or government change,” the demonstrators warned in a statement. The group dispersed after Tehran’s police chief talked with the group, which did not have an official permit to gather.

Cultural Issues

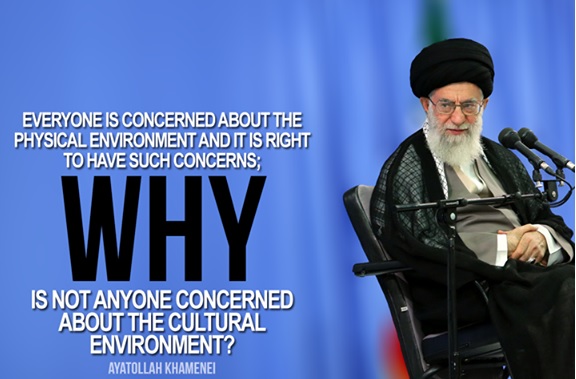

Shortly after his election, Rouhani said, “A strong government does not mean a government that interferes and intervenes in all affairs.” But Khamenei and other conservatives have warned Rouhani’s government against loosening cultural controls. “Entrusting cultural issues to the people does not negate the regulatory role and guidance of the administration,” Khamenei said at High Council of Cultural Revolution meeting in December. In March, Khamenei said the Rouhani administration should pay attention to cultural issues and advised officials to not be “reckless.”

Shortly after his election, Rouhani said, “A strong government does not mean a government that interferes and intervenes in all affairs.” But Khamenei and other conservatives have warned Rouhani’s government against loosening cultural controls. “Entrusting cultural issues to the people does not negate the regulatory role and guidance of the administration,” Khamenei said at High Council of Cultural Revolution meeting in December. In March, Khamenei said the Rouhani administration should pay attention to cultural issues and advised officials to not be “reckless.” Even the Revolutionary Guards have weighed in. In April, General Mohammad Ali Jafari said that cultural threats are “the most important threats presently facing the Islamic Revolution” and that the revolution’s “fundamental essence” is “opposing the dominant [Western] system.”

On May 9, two influential hardliners warned Rouhani’s government against expanding freedoms. Tehran’s Friday prayer leader Ayatollah Movahedi Kermani told Rouhani’s culture and science ministers in a sermon to avoid “returning to the Reformist period in the fields of culture and morality.”

Ayatollah Mesbah Yazdi, one of Rouhani’s harshest critics and the leader of the ultraconservative Endurance Front, warned against following the teachings of the West. He had earlier blamed “those who were educated in the United Kingdom, United States and France” for the cultural division in Iran. The comment appeared to be an indirect potshot at Rouhani and his cabinet, which includes several ministers who earned university degrees in the West—including the U.S.-educated head nuclear negotiator and foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif. Rouhani earned a law degree from Glasgow Caledonian University in Scotland.

Photo credit: Rouhani via President.ir, Tehran bazaar photo by Robin Wright, Khamenei.ir via Facebook

Garrett Nada is the assistant editor of The Iran Primer at USIP.