Gary Sick

A government negotiating with another government is almost inevitably required to conduct a second negotiation with its own domestic constituents whose own interests will be affected by the outcome. The classic image is the negotiator facing his foreign adversary over one table, then swiveling around to confront his domestic adversaries at a second table.

A government negotiating with another government is almost inevitably required to conduct a second negotiation with its own domestic constituents whose own interests will be affected by the outcome. The classic image is the negotiator facing his foreign adversary over one table, then swiveling around to confront his domestic adversaries at a second table. In the current negotiations with Iran over the future of its nuclear program, the United States is facing something even more daunting. It is engaged in at least four separate negotiations at the same time:

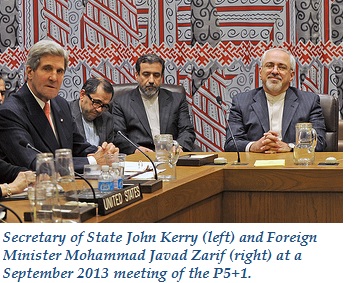

1) Direct talks with Iran

2) Consultations with its negotiating partners in the so-called P5+1 – the five Permanent Members of the United Nations Security Council plus Germany – who must develop a unified bargaining position

3) Congress of the United States

4) Allies such as Israel and Saudi Arabia, whose interests will be impacted by the outcome.

Success in one dimension of this chess match does not necessarily guarantee success in any of the others, although in the end a successful final outcome will require at least a measure of success in all four dimensions. Ironically, crafting an agreement with Iran could prove to be the easiest part of the diplomatic game. The most difficult challenge may be in the domestic political arena, particularly in the United States. Iran’s hardliners are also poised to challenge potential concessions.

The following is a brief snapshot of the board so far:

Engagement with Iran

By almost any measure, direct contact between U.S. negotiators and their counterparts in Iran has exceeded expectations. American official contact with Iranian officials has been rare, sporadic, and often almost illicit for most of the past 35 years, since the Iranian revolution and the subsequent hostage crisis. U.S. diplomats were often instructed to avoid even casual contact with Iranian dignitaries at routine diplomatic functions. The United States and Iran occasionally worked together openly, such as at the Bonn conference in December 2001, when Hamid Karzai was selected as the president of a new Afghan government. But the relationship had never been able to transcend longstanding political animosity.

By almost any measure, direct contact between U.S. negotiators and their counterparts in Iran has exceeded expectations. American official contact with Iranian officials has been rare, sporadic, and often almost illicit for most of the past 35 years, since the Iranian revolution and the subsequent hostage crisis. U.S. diplomats were often instructed to avoid even casual contact with Iranian dignitaries at routine diplomatic functions. The United States and Iran occasionally worked together openly, such as at the Bonn conference in December 2001, when Hamid Karzai was selected as the president of a new Afghan government. But the relationship had never been able to transcend longstanding political animosity. That has now changed. A senior U.S. official, who regularly briefs the media on the progress of the negotiations, said the United States and Iran no longer need to hold secret meetings. “When we need to solve problems, [we] email with the Iranians,” the official said. That kind of routine contact suggests that a return to the tensions of the past is progressively less likely – whether or not the current negotiations succeed.

Coordination with Allies

The progress of negotiations so far has been achieved by coordination and discipline among the six major powers—Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia and the United States—who sit on the same side of the table opposite Iran. The cohesion appears to be genuine. The talks have also not been contaminated by policy clashes—especially between Washington and Moscow—over Syria, the Crimea, and East Asia, which could have intruded on the Iran negotiations.

The progress of negotiations so far has been achieved by coordination and discipline among the six major powers—Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia and the United States—who sit on the same side of the table opposite Iran. The cohesion appears to be genuine. The talks have also not been contaminated by policy clashes—especially between Washington and Moscow—over Syria, the Crimea, and East Asia, which could have intruded on the Iran negotiations. The senior U.S. administration official, speaking on background, addressed those issues after the meetings in Vienna on March 19, at a time when the Crimean crisis was dominating the media: “The P5+1… is very united. We may have some different ideas, we may even have national positions which aren’t identical, but when we are in the room together, we are completely united. . . Everybody is very professional, very serious, very focused. If there is any humor, it’s of the good-natured variety. There are no histrionics. There’s no walking out. There’s no yelling and screaming. It is very professional, very workmanlike.”

The parties have also not digressed from the main topic into other important but tangential issues, such as human rights abuses, ties to extremist forces such as Hezbollah, and Tehran’s support for the Syrian government. The major powers appear to have decided to defer such discussions until the nuclear issue has been resolved one way or another.

The U.S. Congress

Many senators, both Republicans and Democrats, are intensely skeptical of the talks. Even before negotiations had begun in earnest, 59 senators from both parties supported a new round of sanctions, including a commitment to support Israel in the event it should attack Iran, a clear signal about potential future opposition. The Obama administration strongly opposed the bill, which did not get sufficient Democratic support to bring it to a vote.

Many senators, both Republicans and Democrats, are intensely skeptical of the talks. Even before negotiations had begun in earnest, 59 senators from both parties supported a new round of sanctions, including a commitment to support Israel in the event it should attack Iran, a clear signal about potential future opposition. The Obama administration strongly opposed the bill, which did not get sufficient Democratic support to bring it to a vote. The administration has been careful to brief members of Congress throughout the negotiations, and the executive branch has diligently enforced existing sanctions during talks. Yet Congress may still intervene once terms of a deal are known. In the past, legislators have called for Iran’s program--including all centrifuges and enrichment sites—to be completely dismantled. Opposition has invoked “the four no’s: no enrichment, no centrifuges, no stockpile of enriched uranium, and no heavy water reactor.”

The administration has signaled that those terms exceed the requirements of the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty. It is expected to present any agreement with Iran as an executive agreement not requiring a two-thirds vote of the Senate for ratification. Nevertheless, cooperation with the Congress will be required in order to remove the many layers of sanctions imposed on Iran over the past 35 years. Most observers expect this domestic negotiation to be even more rancorous than the actual negotiations with Iran.

Regional Allies

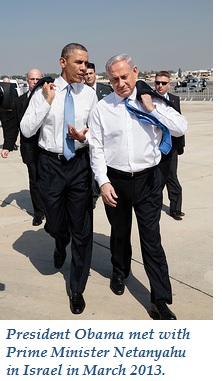

The concerns of regional states – notably Israel and Saudi Arabia– constitute the fourth dimension of this complex negotiation that a senior U.S. official has described as a Rubik’s Cube. Prime Minister Netanyahu has been outspoken in questioning the prospective nuclear deal, especially if Tehran is allowed to retain any ability to enrich uranium. In a CNN interview on April 27, he denounced it as “a terrible deal,” since it would leave Iran as a nuclear threshold state. He told an American audience: “Don’t let it happen.” That perspective could influence Congressional opposition.

The concerns of regional states – notably Israel and Saudi Arabia– constitute the fourth dimension of this complex negotiation that a senior U.S. official has described as a Rubik’s Cube. Prime Minister Netanyahu has been outspoken in questioning the prospective nuclear deal, especially if Tehran is allowed to retain any ability to enrich uranium. In a CNN interview on April 27, he denounced it as “a terrible deal,” since it would leave Iran as a nuclear threshold state. He told an American audience: “Don’t let it happen.” That perspective could influence Congressional opposition.

Gary Sick, principal White House aide for Iran and the Persian Gulf on the Carter administration’s National Security Council, is now executive director of Gulf/2000, an international online research project on the Persian Gulf at Columbia University.

Click here to read his chapter on the Carter administration and Iran.

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org

Photo credits: Chess board by Prayitno/ more than 1.5 millions views: thank you! (Flickr: Chess) [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, UNGA Ashton Security Council by European External Action Service via Flickr