Garrett Nada

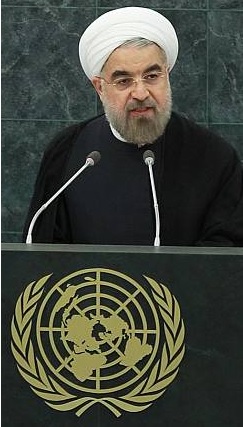

Israel is the most skeptical country about diplomacy to ensure Iran does not develop a nuclear weapon. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has generally dismissed Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s diplomatic overtures to the outside world as a deceptive “charm offensive.” In his U.N. address, Netanyahu called Rouhani a “wolf in sheep’s clothing” and then went on a media blitz to warn world leaders against trusting the new president’s more conciliatory tone.

Israel and Iran differ on a key issue: Iran insists that it retain the right to enrich uranium, a process for its peaceful nuclear energy program. But Israel insists that it end all enrichment because the fuel cycle could also be used to eventually develop a nuclear bomb.

Israel and Iran differ on a key issue: Iran insists that it retain the right to enrich uranium, a process for its peaceful nuclear energy program. But Israel insists that it end all enrichment because the fuel cycle could also be used to eventually develop a nuclear bomb. On November 8, Netanyahu warned against an interim agreement being discussed by world’s six major powers and Iran in Geneva. The agreement reportedly would relax some financial sanctions in return for Iran halting its nuclear program. “Iran is not required to take apart even one centrifuge,” Netanyahu said. “It’s the deal of a century for Iran; it’s a very dangerous and bad deal for peace and the international community."

After the Geneva talks ended, Israel stepped up its campaign against what it considered premature sanctions relief for Iran. Economy Minister Naftali Bennett said that he would use a previously scheduled visit to Washington to warn Congress about the dangers of an interim deal. “Before the talks resume [on November 20], we will lobby dozens of members of the U.S. Congress to whom I will personally explain during a visit beginning on Tuesday that Israel's security is in jeopardy,” he said on November 10.

In an English-language press conference, Strategic Affairs Minister Yuval Steinitz claimed that the United States, China, Britain, France, Germany, and Russia were considering “significant relief for the Iranians.” He estimated that U.S. and E.U. sanctions had cost Iran some $100 billion annually and that the proposed sanctions relief package could be worth up to $40 billion— or 40 percent of the overall impact. But State Department Spokesperson Jennifer Psaki dismissed the estimate as “inaccurate, exaggerated, and not based on reality” in a briefing on November 13.Two days later, Netanyahu's office released the above graphic warning against an interim deal ahead of the third round of talks since Rouhani took office.

In an English-language press conference, Strategic Affairs Minister Yuval Steinitz claimed that the United States, China, Britain, France, Germany, and Russia were considering “significant relief for the Iranians.” He estimated that U.S. and E.U. sanctions had cost Iran some $100 billion annually and that the proposed sanctions relief package could be worth up to $40 billion— or 40 percent of the overall impact. But State Department Spokesperson Jennifer Psaki dismissed the estimate as “inaccurate, exaggerated, and not based on reality” in a briefing on November 13.Two days later, Netanyahu's office released the above graphic warning against an interim deal ahead of the third round of talks since Rouhani took office. Israel is also concerned that a diplomatic deal between Iran and the world’s six major powers—the United States, Britain, China, France, Germany and Russia—would allow Iran to reemerge as a regional powerhouse.

Israel’s opposition to a deal are based on Iran’s potential to:

• Improve its military capabilities

• Ramp up support for extremist groups

• Improve ties with the United States

• Gain international legitimacy

The Military Balance

Israel is concerned that Iran might use the knowledge and technology used for building a nuclear weapon as leverage to expand its sphere of influence. As an undeclared nuclear power, Israel would still have the military edge. It is widely reported to have at least 80 nuclear warheads, with materiel to make up between 155 to 190 more. And unlike the Gulf sheikhdoms, Israel is hundreds of miles from Iran. So it is not primarily worried about potential land or sea battles in the conventional sense. Jerusalem is mainly focused on how Iran could threaten it from a distance, particularly via long-range missiles, or by increasing its influence with Israel’s neighbors.

Iran “continues to develop missiles of various ranges, including intercontinental ballistic missiles designed to carry nuclear warheads. These missiles pose a threat to the Middle East, Europe, the United States and other countries,” Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu warned in his U.N. address on Oct. 1, 2013.

The Islamic Republic has the largest and most diverse arsenal of long-range rockets and ballistic missiles in the Middle East. Tehran already possesses missiles, such as the Shahab-3 and Ghadr-1, that are theoretically capable of hitting Israel. They are, however, also highly inaccurate. Israel is concerned that Tehran is capable of producing longer range missiles. In an unprecedented display in September, Tehran paraded 30 missiles with a range of 1,200 miles to mark the anniversary of Iraq’s 1980 invasion.

The Islamic Republic has the largest and most diverse arsenal of long-range rockets and ballistic missiles in the Middle East. Tehran already possesses missiles, such as the Shahab-3 and Ghadr-1, that are theoretically capable of hitting Israel. They are, however, also highly inaccurate. Israel is concerned that Tehran is capable of producing longer range missiles. In an unprecedented display in September, Tehran paraded 30 missiles with a range of 1,200 miles to mark the anniversary of Iraq’s 1980 invasion. For now, Israel’s missiles are much more advanced and accurate. The Jericho II, with its estimated 900-mile range, could hit Tehran. In July 2013, Israel reportedly tested a new generation missile that could be the Jericho III. It has a range of between 3,100 miles and 6,800 miles, capable of hitting all corners of Iran. Israel may still worry that an emboldened Iran could deliver missiles to proxies closer to Israel’s borders, such as Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Side Effects of a Deal

Israel and Iran were the two main pillars of U.S. policy in the Middle East until the 1979 revolution. Since then, Israel and the United States have had a shared interest in containing Iran. They reportedly worked together on cyber warfare to slow or disrupt Iran’s nuclear program. The Stuxnet worm reportedly attacked Iran’s centrifuges in late 2009 or early 2010, while the Flame virus collected information on Iranian officials in 2012.

But Tehran’s new diplomatic initiative — including the first meeting between Iranian and American foreign ministers and a telephone call between Presidents Obama and Rouhani in September —unnerved Israeli leaders. They are concerned about the side-effects of any deal, including lifting sanctions and potential rapprochement with the United States.

A deal that lifts the world’s toughest sanctions could in turn improve Iran’s economic health and generating new income to support extremist groups, such as Hezbollah and Hamas. By October 2013, sanctions had cost Iran at least $100 billion just over the previous 18 months, Israeli Intelligence Minister Yuval Steinitz told Foreign Policy magazine. In 2006, Israel fought its longest war with Hezbollah; it ended without a clear victory for either side. Israel has a strategic interest in making sure Tehran does not replenish Hezbollah’s stock of weapons.

International Legitimacy

Israel is also concerned that a nuclear deal could lead to Iran’s acceptance by a wider international community. Tehran has had pariah status, particularly under former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Even Iran’s powerful allies Russia and China backed punitive U.N. sanctions when Tehran refused to comply with international resolutions. But a deal on Tehran’s controversial nuclear program could be a game changer—and even draw unwanted attention on Israel’s undeclared nuclear weapons.

Israel is also concerned that a nuclear deal could lead to Iran’s acceptance by a wider international community. Tehran has had pariah status, particularly under former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Even Iran’s powerful allies Russia and China backed punitive U.N. sanctions when Tehran refused to comply with international resolutions. But a deal on Tehran’s controversial nuclear program could be a game changer—and even draw unwanted attention on Israel’s undeclared nuclear weapons. President Rouhani has already called for Israeli transparency on its program. “Almost four decades of international efforts to establish a nuclear-weapon-free zone in the Middle East have regrettably failed,” Rouhani said in his speech to a U.N. disarmament conference. “Israel, the only non-party to the Non-Proliferation Treaty in this region, should join thereto without any further delay.”

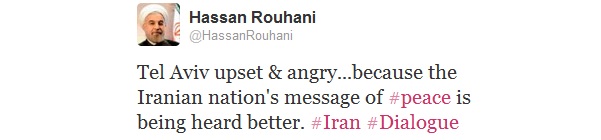

Iran's Take on Israel's Reaction

Tehran is aware of Israel’s growing anxiety over nuclear negotiations and new U.S.-Iran interaction. In an October 3 tweet, President Rouhani’s office suggested that Israel was jealous of the attention Iran’s diplomatic overtures have received.

Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif interpreted Israel’s media blitz as a “sign of the frustration of warmongers.” He also implied that Jerusalem’s position would be diminished by a nuclear agreement. On October 18, he wrote on his Facebook page, “Zionists have the most fear about the success of the talks.”

Garrett Nada is a senior program assistant at USIP.

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org