By Garrett Nada and Helia Ighani

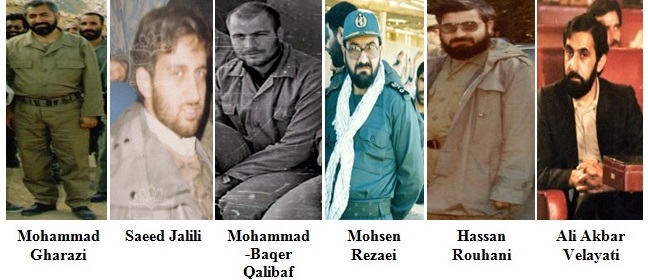

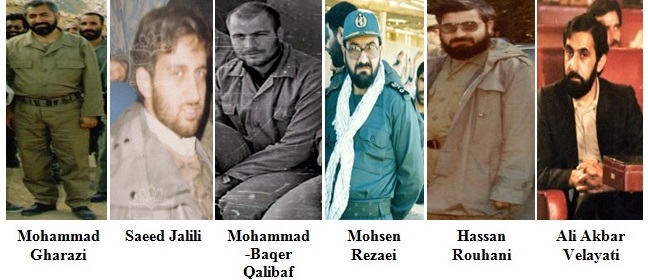

A quarter century later, the Iran-Iraq War looms over Iran’s presidential election as if it happened yesterday. All six candidates participated in the grizzliest modern Middle East conflict as fighters, commanders or officials. Over the past month, the campaign has evolved into a feisty competition over who sacrificed and served the most in the eight-year war.

A leading candidate lost a leg. Another candidate commanded the Revolutionary Guards. A third liberated an oil-rich frontline city. A fourth brokered the dramatic ceasefire.

During the final debate on June 7, candidates invoked their wartime experience during the “Holy Defense,” as it is officially dubbed in Iran, as a top credential for taking office. It clearly shaped the worldviews of all six, despite their disparate political affiliations as reformists, hardliners or independents.

But experience during the 1980-1988 war is also emerging as an unspoken credential in facing the future, specifically a confrontation with the outside world over Iran’s controversial nuclear program. The debate resonated with language of resistance that echoed from the war, which claimed up to 1 million casualties.

Iran’s presidential contest illustrates how the war generation is now competing to take over the leadership from the first generation of revolutionaries. Four out of the six candidates were connected to the Revolutionary Guards, Iran’s most powerful military organization. Over the past decade, the Guards have also played an increasing role in the economy and politics. Veterans won nearly a fifth of parliament’s 290 seats in 2004.

The six candidates had vastly different roles.

Saeed Jalili, a hardliner who is today Iran’s chief nuclear negotiator and secretary of Supreme National Security Council, earned the title of “living martyr” when he lost part of his right leg fighting on the front. He served in the Basij paramilitary under the Guards.

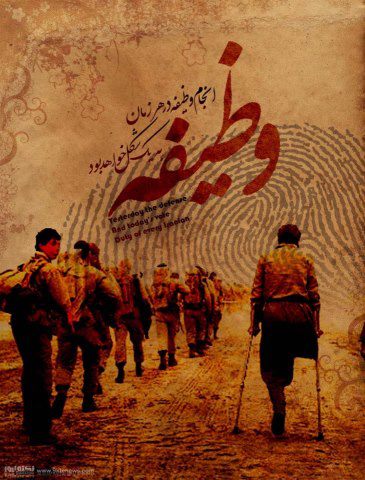

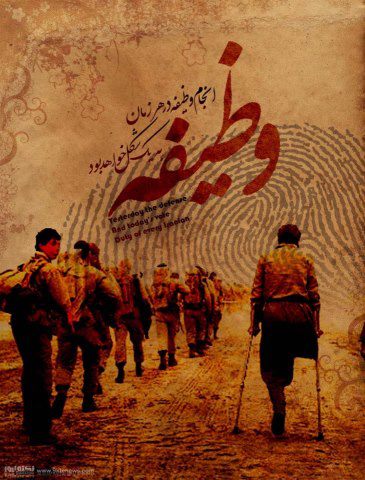

Jalili’s campaign has centered on war imagery and language in his campaign. His slogan — plastered across posters, his website and social media — is “Resistance is the key to success.”

A promotional video shows Iranian forces destroying an Iraqi tank during the war. Jalili’s campaign tweeted

a picture of himself in a military uniform labeled, “A former soldier, a current diplomat.” His campaign posted a graphic (left) encouraging Iranians to fulfill “today’s” national duty to vote while recalling the past duty to defend the nation.

He implies the same toughness from his war years will form his foreign policy. “We will not retreat one iota from our basic rights” to nuclear technology, Jalili told supporters on June 3.

Mohammad-Baqer Qalibaf, the current mayor of Tehran and another hardliner, has invoked his war experience as much as his eight years running Iran’s largest city. He claims to have played a leading role in recapturing the city of Khorramshahr from Iraqi forces in 1982, a turning point commemorated annually in Iran. He climbed the ranks of the Revolutionary Guards during the war and in 1998 became commander of its air force.

A posting on his campaign Google Plus profile argued that only “a culture of jihad and martyrdom” can save Iran. He has used his war credentials to reject attempts to label him a technocrat. “I believe that a person is a technocrat [if they have] not seen the color of the front,” he said on June 6.

Of all the candidates, Mohsen Rezaei (left) arguably played the most high-profile role in the war. He was named chief Revolutionary Guards commander in 1981, a position he held until 1997. An independent, Rezaei regularly cites his military leadership as a qualification for president. In the final debate on June 7, he called for the end of partisan politics, claiming that he engaged with all factions as Revolutionary Guards chief.

Of all the candidates, Mohsen Rezaei (left) arguably played the most high-profile role in the war. He was named chief Revolutionary Guards commander in 1981, a position he held until 1997. An independent, Rezaei regularly cites his military leadership as a qualification for president. In the final debate on June 7, he called for the end of partisan politics, claiming that he engaged with all factions as Revolutionary Guards chief. Rezaei’s website features a

gallery devoted to pictures of him from the conflict with Iraq. “During the war, I was nearly captured three times. I like to fully examine the enemy before an operation,”Rezaei said.

Mohammad Gharazi, an independent, helped build the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps to support the new theocracy. But it ended up playing the pivotal role in the war. During the war’s early years, Gharazi was governor of southwestern Khuzestan province, where some of the bloodiest battles took place. He also served in various ministerial posts. In the first presidential debate on May 31, he claimed that his generation “carried out a revolution, fought a war, and brought peace.”

Even Hassan Rouhani — a reformist and the only cleric in the race — has compared his fearlessness on the war front to the presidential race. From 1982 to 1988, he was a member of the Supreme Defense Council. He was named chief of Iran’s air defense in 1985. After the war, he became head of Iran’s National Security Council from 1989 to 2005. Rouhani recently tweeted that he’s “not afraid of anybody in the world,” and that he’s “the same solider who served 8 years in the Iran-Iraq war.”

Former Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Velayati, a hardliner, was Iran’s chief diplomat during the war, dealing with repeated peace efforts by the international community. He presided over the negotiations that led to a ceasefire. He now claims that his diplomatic experience makes him the best person to solve Iran’s dispute with the international community over Tehran’s nuclear program. “What we did during the Iran-Iraq War in international diplomacy was much more difficult than nuclear negotiations,” he claimed during the June 7 debate.

Ironically, negotiating the ceasefire made Velayati vulnerable. In the last debate, Qalibaf accused the former foreign minister of drinking coffee with the French president in Elysee Palace while he and other soldiers were dodging missiles on the front.

Although the war ended twenty-five years ago, its haunting memories may still impact voters when they go to the polls on Friday. Virtually every family suffered a death or a casualty. Billboards of martyrs along streets of cities across the country keep their memory fresh. Many towns have special cemeteries for “martyrs” in the war and museums to the dead, complete with their bloodied uniforms and letters from the war front. Iran’s youth learn about the “Holy Defense” in school.

The war also cost Iran dearly in economic terms. It cost Iran approximately $637 billion, according to one estimate. The total damage to the economy was equivalent to 77 percent of the country’s total economic output during those eight years.

The young Islamic Republic resisted a ceasefire that would cede territory or rights to a strategic waterway, the issue that led to Saddam Hussein’s invasion. Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini only grudgingly accepted a U.N.-brokered ceasefire in August 1988. He said ending the war without a clear victory was “more deadly than drinking hemlock.”

Iranians want to avoid having to drink hemlock — or compromising on principle or sovereignty — again. The candidates, whatever their politics, are playing to that popular sentiment.

Garrett Nada is a Program Assistant in the Center for Conflict Management at the United States Institute of Peace.

Helia Ighani is recent graduate from the George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs and a research assistant at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org

Saeed Jalili, a hardliner who is today Iran’s chief nuclear negotiator and secretary of Supreme National Security Council, earned the title of “living martyr” when he lost part of his right leg fighting on the front. He served in the Basij paramilitary under the Guards.

Saeed Jalili, a hardliner who is today Iran’s chief nuclear negotiator and secretary of Supreme National Security Council, earned the title of “living martyr” when he lost part of his right leg fighting on the front. He served in the Basij paramilitary under the Guards. Of all the candidates, Mohsen Rezaei (left) arguably played the most high-profile role in the war. He was named chief Revolutionary Guards commander in 1981, a position he held until 1997. An independent, Rezaei regularly cites his military leadership as a qualification for president. In the final debate on June 7, he called for the end of partisan politics, claiming that he engaged with all factions as Revolutionary Guards chief.

Of all the candidates, Mohsen Rezaei (left) arguably played the most high-profile role in the war. He was named chief Revolutionary Guards commander in 1981, a position he held until 1997. An independent, Rezaei regularly cites his military leadership as a qualification for president. In the final debate on June 7, he called for the end of partisan politics, claiming that he engaged with all factions as Revolutionary Guards chief.