Mehdi Khalaji

Iran and Syria are unlikely bedfellows. Iran has been an Islamic republic—and the world’s only modern theocracy—since the 1979 revolution. Syria has been a rigidly secular and socialist country since Hafez Assad took over in 1970. Ethnically, Iran is predominantly Persian, while Syria is predominantly Arab. Yet Tehran and Damascus have one of the region’s strongest alliances—based in part on religion. Iran is Shiite-dominated and Syria is predominantly ruled by Alawites, a Shiite offshoot. They share a common interest in the survival of a minority in the Middle East, which is about 85 percent Sunni Muslim.

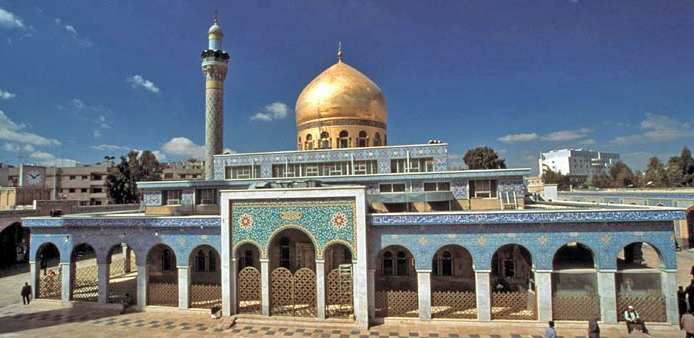

The ties were again reflected in the Iranian regime’s call for volunteers to protect Shiite shrines in Syria in early May 2013, after Syrian rebels reportedly ransacked the shrine of Hojr Ibn Oday, a revered Shiite figure, in Damascus. The Nusra Front, a Sunni militia affiliated with al Qaeda, claimed responsibility for exhuming Oday’s remains. Syria is home to some 50 Shiite shrines and holy places. For centuries, Iranians have performed pilgrimages to Syria. The holiest is the Tomb of Zaynab (left) on the outskirts of Damascus. Mehdi Khalaji explains the religious ties that bind two of the most strategically important countries in the Middle East.

The ties were again reflected in the Iranian regime’s call for volunteers to protect Shiite shrines in Syria in early May 2013, after Syrian rebels reportedly ransacked the shrine of Hojr Ibn Oday, a revered Shiite figure, in Damascus. The Nusra Front, a Sunni militia affiliated with al Qaeda, claimed responsibility for exhuming Oday’s remains. Syria is home to some 50 Shiite shrines and holy places. For centuries, Iranians have performed pilgrimages to Syria. The holiest is the Tomb of Zaynab (left) on the outskirts of Damascus. Mehdi Khalaji explains the religious ties that bind two of the most strategically important countries in the Middle East. What religious doctrines do Shiites and Alawites share? How have the Iranian and Syrian regimes bonded through belief?

The Alawite sect is a relatively minor branch of Shiism. Alawis share the Shiite belief that leadership of the Islamic world—and rights to interpret the faith—should have descended through Prophet Mohammed’s family after his death. They believed that Ali—who was both the prophet’s cousin and son-in-law—should have become the first caliph in the 7th century. Shiite literally means “follower of Ali.” In contrast, Sunnis believe that leadership should instead be inherited by the prophet’s early advisers. Ali was briefly the fourth caliph, but otherwise leadership of the Islamic world has since been largely dominated by Sunnis.

Since the 9th century, Alawites struggled for legitimacy and recognition from other Muslims. One important breakthrough was a fatwa issued in the 1970s by Musa Sadr, an Iranian cleric and head of Lebanon’s Shiite community. He formally announced the acceptance of Alawites as Shiites, a move that significantly opened the way for the sect’s recognition within the general Shiite community.

In recent decades, Twelver Shiites have also made serious efforts to minimize theological differences between mainstream Shiism and Alawites. This has been partly due to the decline of Arab nationalism and rise of the religious factor in making political alliances and defining identity. The shift is palpable in many ways. Shiite clergy use Damascus as a bridge to connect Shiites in Iran, Iraq, Kuwait and Lebanon together. The Syrian government has allowed Shiites to visit various holy sites, especially the Sayyidah Zaynab Mosque.

How are Alawites different from Shiites?

Alawites, or “Alawis,” are primarily known in the Islamic orthodoxy as “Nusayris.” Nusayri-Alawi is an esoteric sect that is relatively unstudied because members have historically kept core beliefs secret.

In terms of theological principles, rituals, and jurisprudence, Twelver Shiism and the Nusayri-Alawi faith have few commonalities. (Iran practices Twelver Shiism, so named because of the belief in twelve divinely ordained Imams, or leaders.) For centuries, Nusayri-Alawis were actually considered heretics by both Shiites and Sunnis and often faced persecution. For instance, they venerate Ali as a supreme and eternal God.

They were only embraced by Muslims under certain advantageous political circumstances. Their historical position is similar to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints among Christians. Both experienced difficulties being recognized by the orthodoxy. Both are secret sects. And outsiders have minimal access to their core beliefs and administration.

One major difference between the two Shiite branches is the source of religious authority. Twelver Shiites are led by an ayatollah, who is the source of emulation on juridical issues and rituals. The faithful are also obligated to pay religious taxes to their ayatollahs. But Alawis do not have ayatollahs. So the two sects have not historically had the same religious-financial bonds.

What are the political bonds between Iran’s Shiites and Syria’s Alawites?

The political bonds between Shiites and Alawites are more about identity and survival of a minority than about religious doctrine. The Middle East is dominated by Sunnis. Iran and Iraq are the only Shiite majority countries in the region, while Syria was for decades the only major Arab country ruled by the Shiite offshoot. Iraq was ruled for nearly a quarter century by Saddam Hussein, a Sunni. So Iran and Syria have had natural psychological bonds that turned into a political alliance over common religious identity. The bonds were further fostered after the rise of a Shiite-dominated government in Iraq—the country that separates them—in 2003. This nascent Shiite bloc was dubbed the “Shiite crescent” by Jordan’s King Abdullah.

The bonds are also strategic for two isolated governments. The Assad regime’s need for allies in Iran and Lebanon made it ignore the theological differences between Twelver Shiism and Nusari-Alawis. The Islamic Republic of Iran, spurned by the region’s Sunni-led governments, made ties with Alawite brethren in Syria particularly appealing—even though Tehran has actually never referred to Damascus as an Alawi regime. Its official policy toward Muslim countries has been to highlight Islam rather than its specific branches.

In the end, Iran and Syria actually have very different types of government. Syria’s ruling elite may be Alawite, but the government’s official ideology is Ba’athism, a secular mix of socialism and pan-Arabism. The Ba’ath party is also not only Alawite. It also includes some Sunnis and Christians.

The governments in Syria and Iran also have different ties to their constituencies. The Alawites are only about 12 percent of the Syrian population. Syrians are predominantly Sunni. In Iran, more than 90 percent of the population is Shiite.

Mehdi Khalaji, a senior fellow at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, studied Shiite theology in the Qom seminary of Iran.

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org