John Limbert

What is the lesson of “Argo” when it comes to dealing with Iran?

The historical thriller has swept the awards season. “Argo” probably has a better chance of winning an Oscar on February 24 than the negotiators have of breaking their long deadlock. The film’s real lesson is that the events of 1979 still have the power to affect events today. The hostage crisis casts its shadow over Iran’s relations with the United States and other nations.

Attitudes shaped by those events have led both sides to expect rapprochement efforts to fail— including the upcoming negotiations between the six world powers and Iran scheduled for February 26. Both Iran and the United States must deal with their past grievances to move on.

How does the 1979 hostage ordeal shape Iran and U.S. attitudes today?

How does the 1979 hostage ordeal shape Iran and U.S. attitudes today? “Argo” highlights the negative attitudes that the two countries have held toward each other for the past three decades. Its brief introduction attempted to provide historical context behind the embassy takeover. But the film did not convey the prevailing Iranian sense of grievance—real or imagined—that led to the attack, and to the emotional response in the streets of Tehran.

Jimmy Carter’s administration was oblivious to the depths of resentment and fury in revolutionary Iran, and to the suspicion that would greet the October 1979 decision to admit the shah to the United States for medical treatment. Many Americans still do not understand that resentment, which many Iranians still hold. The film may have reinforced stereotypes of Iranians as violent, fanatical and deceitful.

The Iranian government has also been oblivious to the effect of issuing commemorative stamps and holding annual rallies to mark the embassy takeover. These actions have reinforced the perception that Iranians are irrational or that they will not negotiate in good faith with the United States. Mohammad Khatami’s presidency from 1997 to 2005 was a notable exception, as turnouts for rallies were significantly lower at that time.

The current presidents of both countries have noted the importance of perceptions and attitudes. In a 2009 interview with Al Arabiya, President Obama said that negative “preconceptions” hamper peace efforts in the Middle East. President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad decried the “negative mentality” (zehniyat-e manfi) between Iran and the United States in comments to American academics in October 2012.

What has been the Iranian response to “Argo”?

“Argo” has ripped a scab off an old wound and reminded many Iranians of an ugly chapter in their history. The film has forced Iranians to confront the events of 1979. Until now, many Iranians, including Ahmadinejad, had treated the events surrounding the embassy takeover as ancient history. In September 2010, I asked Ahmadinejad about the hostage crisis. “You were treated well, weren’t you?” he said. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei expressed the same attitude in April 1980, while I was a hostage with 51 other Americans. He visited the hostages and told the press that they were “very happy and even thanked their captors for treating them so well.”

The film has exacerbated a deep divide among Iranians. Private showings of “Argo” have reportedly revived the debate on the wisdom or folly of the embassy takeover, and how the government allowed the student sit-in to become a major international crisis.

Critics of the embassy takeover claim it sent Iran careening down a course of war, brutality, extremism, repression, and international isolation. They argue that it unleashed a torrent of hysteria that destroyed any chance that the revolution would lead to something better for most Iranians. The takeover is a source of shame for some. But others seem proud of the students who stormed the embassy.

Some Iranians have criticized “Argo” for its portrayal of post-revolution Iran. “We Iranians look stupid, backward, and simple-minded in this movie,” a self-described film specialist told The New York Times at a conference in Tehran in February. Participants of the third annual “Hollywoodism” conference claim there is a hidden agenda behind American films like “Argo.”

How might the outcome of the upcoming negotiations be based on past fears and lack of trust?

Iranian distrust of the United States could be an obstacle to multilateral negotiations. “There are many reasons for this distrust,” said Supreme Leader Khamenei in a February 2013 speech. He claimed that Iranian officials have been harmed whenever they trusted the United States during the past 60 years. Secretary of the Expediency Council Mohsen Rezai claimed the United States has “stonewalled” negotiations with the P5+1 in remarks to Fars News Agency in February.

The next round of negotiations is unlikely to produce a breakthrough in this atmosphere of suspicion, mistrust, and festering wounds. Negotiators from Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia and the United States—the so-called P5+1—are scheduled to discuss the nuclear issue with their Iranian counterparts in Kazakhstan on February 26.

Iran and the United States need to leave their old resentments and suspicions behind to move forward. On the nuclear issue, both sides have painted themselves into rhetorical corners. Officials frame the conversation in terms of one side’s rights and the other’s obligations. There is little room for progress as long as the two sides confine their discussions to this difficult issue.

Neither side can afford to make concessions that the other could accept. The United States cannot backtrack on sanctions and Iran cannot suspend uranium enrichment. Simply put, the Iranians want what the Americans cannot give them.

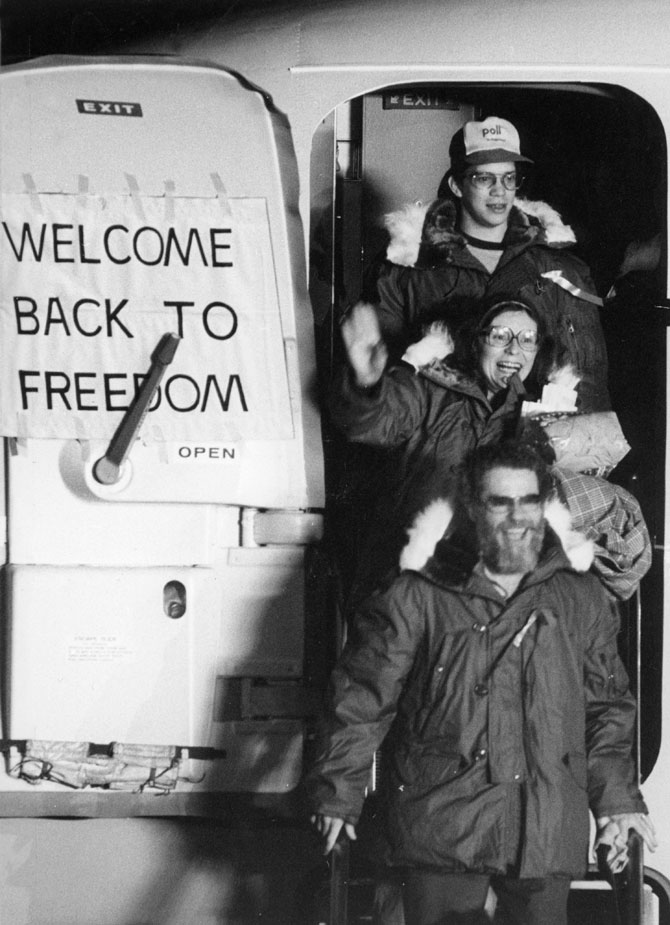

John Limbert was appointed Distinguished Professor of International Affairs at the U.S. Naval Academy in 2006 after 33 years of service with the State Department. The ambassador briefly returned to the State Department and served as deputy assistant secretary for Iran from November 2009 through July 2010. In 1979, he was posted at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and was captured along with 51 other Americans. They were held hostage for 444 days.

Photo Credit: The New York Times

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org