The following article first appeared in Time magazine.

Robin Wright

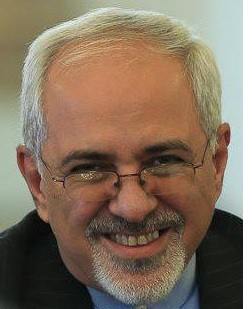

In a wide-ranging interview with TIME in Tehran on Dec. 7, Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammed Javad Zarif spoke to writer and Iran expert Robin Wright about how the Geneva nuclear deal came together, how the government has to appeal to Iran’s own parliament not to undermine the interim pact, and how any new sanctions passed by the United States Congress would kill the deal. The agreement, reached between Iran and six world powers in November, calls for a freeze on parts of Iran’s nuclear program in exchange for an easing of sanctions. It is meant to pave the way for a final settlement between Iran and the international community on Iran’s nuclear program. Iran says the program is for civilian purposes only; world powers fear that it has a military component. Speaking in the ornate Foreign Ministry building, Zarif also indicated that Iran might not be wedded to Syria’s President Bashar Assad, a long-time ally, and he said that Iran hoped for a “duly monitored” democratic election in Syria. Iran’s most high-profile cabinet official warned that the deepening sectarianism playing out in Syria does not recognize borders and has implications “on the streets of Europe and America.”

In a wide-ranging interview with TIME in Tehran on Dec. 7, Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammed Javad Zarif spoke to writer and Iran expert Robin Wright about how the Geneva nuclear deal came together, how the government has to appeal to Iran’s own parliament not to undermine the interim pact, and how any new sanctions passed by the United States Congress would kill the deal. The agreement, reached between Iran and six world powers in November, calls for a freeze on parts of Iran’s nuclear program in exchange for an easing of sanctions. It is meant to pave the way for a final settlement between Iran and the international community on Iran’s nuclear program. Iran says the program is for civilian purposes only; world powers fear that it has a military component. Speaking in the ornate Foreign Ministry building, Zarif also indicated that Iran might not be wedded to Syria’s President Bashar Assad, a long-time ally, and he said that Iran hoped for a “duly monitored” democratic election in Syria. Iran’s most high-profile cabinet official warned that the deepening sectarianism playing out in Syria does not recognize borders and has implications “on the streets of Europe and America.”What are biggest differences between Iran and the six major powers in making a permanent agreement? The biggest issues and obstacles?

There are a number of issues. One is the removal of all sanctions – both U.N. Security Council sanctions as well as national and multilateral sanctions outside the U.N. – and second is the issue of Iran having an enrichment program.

These are the two elements of the final deal that are going to be there. How we shape the final deal to include all these elements will be a matter for discussion. The two other members, Russia and China, may also have concerns but they are more confident about the peaceful nature of our nuclear program.

But what are the obstacles then?

I don’t see any obstacles. I believe it’s rather straightforward. We can reach an agreement but there are some areas which are more difficult than others. One of those areas may be how we make sure that [Iran’s heavy water production plant at] Arak will remain peaceful. It is our intention that it will remain exclusively peaceful but how we give them the necessary assurances that it will remain peaceful that may be one of the more difficult areas.

Why do you even need Arak?

Why do we even need Arak? Because we need to produce radio isotopes for medical purposes and even Arak alone is not enough for us. This was the technology that was available to us. Some people believe that we chose this technology because it provided other options. They’re badly mistaken.

You see you have to look at Iran’s nuclear program from the perspective of denial, the fact that Iran was denied access to technology. And we used or we tried to get access to whatever was available to us and this technology was available to us. Other technologies were not. And we made a lot investment both in terms of human capital as well as in terms of material resources and we have reached almost the end game of getting this research reactor into actual operation. So it’s too late in the game for somebody to come and tell us that we have concerns that cannot be addressed. We have to find solutions. We believe there are scientific solutions for this and we are open to discussing them but that will be one of the more difficult issues.

Are you willing to accept a level of enrichment that is only for facilities that Iran has constructed?

We are going to accept measures that would ensure that our program will remain exclusively peaceful but the rest will have to be decided in the negotiations in good faith. We have no intention of producing weapons or fissile material programs. We do not consider that to be in our interests or within our security doctrine.

What are the prospects that Iran will be part of the Geneva talks on Syria?

If Iran is invited without preconditions Iran will be a part of the talks. I think people will decide to invite Iran if they are interested in having a helpful hand in finding a resolution to the Syrian tragedy and they will decide not to invite Iran to their own detriment. Iran believes that what is happening in Syria can have a huge impact on the future of our region and the future beyond the region. Because we believe that if the sectarian divide that some people are trying to fan in Syria becomes a major issue it will not recognize any boundaries. It will go beyond the boundaries of Syria. It will go beyond the boundaries of this region. You will find implications of this on the streets of Europe and America.

Did you or any other Iranian diplomats discuss Iran’s position on Syria with American diplomats?

No, we didn’t except for a very, very brief sort of reference en passé in my first meeting with John Kerry.

Do you think it’s possible that the many different sides of the Syrian conflict and the outside parties to that conflict can find common ground?

It’s up to the Syrians to decide; we can only help. We can only facilitate. And I think Iran will not be an impediment to a political settlement in Syria. We have every interest in helping the process in a peaceful direction. We are satisfied, totally satisfied, convinced that there is no military solution in Syria and that there is a need to find a political solution in Syria. If you want to prevent a void, the types of consequences that we are talking about, I mean if you want to avoid extremism in this region, if you want to prevent a Syria becoming a breeding ground for extremists who will use Syria basically as a staging ground to attack other countries – be it Lebanon, be it Iraq, be it Jordan, Saudi Arabia, even Turkey – these countries are going to be susceptible to a wave of extremism that will find its origins in Syria and the continuation of this tragedy in Syria can only provide the best breeding ground for extremists who use this basically as a justification, as a recruiting climate in order to wage the same type of activity in other parts of this region.

Is Iran going to stick at the side of Bashar Assad?

We will stick to the side of stability and resolution to Syria. But at the end of the day, we are not going to decide who will rule Syria. It should be the Syrian people to decide. We’re proposing that we should not give ourselves the role that the Syrian people should play.

We’re hearing that you’re still facing tough opposition in the Gulf and that Saudi Arabia doesn’t even want to see you yet.

I was well received by every country in the Persian Gulf that I visited [on a recent trip]. I had extremely positive discussions both on regional issues, the fact that all of them welcomed the Geneva agreement, the fact that all of them considered that as a positive development for security and cooperation in our region, the fact that everyone expected a new chapter in relations between Iran and countries on the southern shore of the Persian Gulf. And that was very encouraging for me.

As for Saudi Arabia, I indicated to them that I was prepared to go to Saudi Arabia. Meetings were arranged. But there was a problem with the meetings. We could not arrange all of the meetings that should have been arranged. We decided to go at a time that was more convenient. It doesn’t mean a political problem between Iran and Saudi Arabia. Now we have differences. In every family you have differences of views, even between brothers and sisters. And we all have our differences. There are issues on which we have different opinions, different approaches, different strategies, different tactics. It wasn’t that they were not prepared to see me.

But you did mention the deepening sectarian gap in the region personified by the differences between Iran and Saudi Arabia.

We both have members of both sects among our population and it’s in our interest to avoid this, to have a cordial and brotherly relations between various Islamic sects. So for Iran and Saudi Arabia, it is important and very significant to reach a common understanding on how to avoid this and not to personify such a sectarian difference.

What opposition are you facing at home to the Geneva deal? And what are you doing about it?

The most opposition here emanates from the lack of trust because we do not have a past on which we can build. It’s a psychological barrier to interaction that we need to overcome. The fundamental reason for opposition: they believe the West and particularly the United States are not sincere, are not interested about reaching an agreement. They believe that they will try to use the mechanism of negotiations in order to derail the process, in order to find new excuses. And some of the statements out of Washington give them every reason to be concerned. Now we know that Washington is catering to various constituencies and is trying to address these various constituencies. We read their statements in the light of their domestic constituency process. But not everybody in Iran does that. We believe that the U.S. government should stick to its words, should remain committed to what it stated in Geneva, both on the paper as well as in the discussions leading to the plan of action.

After all these negotiations, do you see the prospect for working together with the United States on other subjects, including Afghanistan?

We have to wait and see whether the behavior that will be exhibited in the course of negotiations and implementation of our agreements on the nuclear issue creates the necessary confidence for us to move to other areas.

Is there anything different now between Iran and the United States after the talks in Geneva after the process that’s been launched?

In terms of using these talks to foster confidence, I don’t think we have been very successful in that process. Because the talks have been followed by public statements that have not differed that significantly from statements that used to be made before the talks. Basically in this day and age, you don’t have secret negotiations, everything is done is out in the open. You cannot pick and choose your audience. And that is one of the beauties of globalization and one of the hazards of globalization whichever way you want to say it. When Secretary Kerry talks to the U.S. Congress, the most conservative constituencies in Iran also hear him andinterpret his remarks. So it’s important for everyone to be careful what they say to their constituencies because others are listening and others are drawing their own conclusions.

What happens if Congress imposes new sanctions, even if they don’t go into effect for six months?

The entire deal is dead. We do not like to negotiate under duress. And if Congress adopts sanctions, it shows lack of seriousness and lack of a desire to achieve a resolution on the part of the United States. I know the domestic complications and various issues inside the United States, but for me that is no justification. I have a parliament. My parliament can also adopt various legislation that can go into effect if negotiations fail. But if we start doing that, I don’t think that we will be getting anywhere. Now we have tried to ask our members of parliament to avoid that. We may not succeed. The U.S. government may not succeed. If we don’t try, then we can’t expect the other side to accept that we are serious about the process.

What can you tell us about the back channel that began last March?

I can tell you that we started discussing this issue on the sidelines of the P5+1 with various countries but with all the countries that were involved we have normal diplomatic relations. It may become more interesting when it involves the United States. That started a long time ago – probably three years ago. Our nuclear negotiator at that time, Dr. [Saeed] Jalili, met with [Undersecretary of State] Bill Burns on the sidelines of Geneva. And since then, there have been back and forth discussions between Iran and the U.S. inside and on the sidelines of P5+1. So that has taken place and I think with some positive outcome.

Did it make possible, did it facilitate Geneva?

I think had it not been for bilateral discussions between Iran and various members of P5+1 we would not have had a positive outcome. Formal meetings of Iran plus six countries and [Senior E.U. foreign policy official] Cathy Ashton usually remain very formal. If you want to reach agreement you need to talk to all of these individually as well as collectively. So we did talk to all members of the P5+1 individually. But as it was not a big deal for us to talk to France or Russia or even the U.K. For the U.S., it was a different issue. And our discussions with the U.S. on the sidelines of P5+1 became a story in themselves.

How alive is that channel now?

When my colleagues go to Vienna, probably they’ll have side discussions with the U.S. and that’s a very important channel. The U.S. is probably the most important player because it has the largest amount of sanctions against Iran, most of them or all of them illegal in our view. But nevertheless it has a lot of sanctions. It imposes a lot of sanctions on various countries that do business with Iran and that is why it has to do the most. In the resolution, it had a lot to do in the creation of the trouble so it has a lot to do in the resolution of the trouble. So that requires Iran and the U.S. to have a lot of discussions on the sides.

Would you have had Geneva without that back channel with the United States?

Well, hypothetical questions: we would not have been able to reach an agreement without having discussed all various issues on the sidelines of P5+1 with various members, particularly the United States.

This article is reposted from Time magazine.

Robin Wright has traveled to Iran dozens of times since 1973. She has covered several elections, including the 2009 presidential vote. She is the author of several books on Iran, including "The Last Great Revolution: Turmoil and transformation in Iran" and "The Iran Primer: Power, Politics and US Policy." She is a joint scholar at USIP and the Woodrow Wilson Center.