On March 1, Iranians will vote in elections for Parliament and the Assembly of Experts, a body charged with selecting and overseeing the supreme leader. Iranian leaders consider voting a national duty because it represents a commitment to the 1979 revolution and its values. “Everyone should participate in elections,” Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei said on February 18. “It is important to choose the best person, but the priority is for people to participate.”

But the public has been apathetic toward the elections, the first since Mahsa Amini – the young woman arrested by the morality police for an improper head covering – died in police custody in September 2022. The bloody crackdown on the ensuing nationwide protests only added to the public’s disenchantment with the government, which has been building for decades. In 2024, Iranians don't expect an ineffectual parliament to “manifest initiative or the moral fortitude required to address their fundamental socioeconomic challenges and shrinking civil liberties,” Kourosh Ziabari, an Iranian journalist studying at Columbia University, told The Iran Primer.

Voters have grown frustrated with leaders, both conservative and reformist. Despite popular mandates, reformist President Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005) and centrist Hassan Rouhani (2013-2021) were unable to overcome the entrenched resistance of hardliners. Both presidents and “failed to bring meaningful changes during their tenures,” Sina Azodi, a lecturer at George Washington University, told The Iran Primer.

The public grew even more disillusioned after the 2021 presidential election. The powerful Guardian Council – an unelected panel of 12 Islamic jurists and scholars – paved the way for hardliner Ebrahim Raisi’s victory by barring any serious competitors. The turnout, just 48.8 percent, was the lowest for a presidential election in the history of the Islamic Republic. The result “showed that elections in Iran have lost their meaning,” Azodi explained. Failed attempts to rejuvenate the economy and successive crackdowns on protests in 2017, 2019 and 2022 also “eliminated any shred of legitimacy that the government had.”

As in 2021, the 2024 elections failed to attract public interest in part because of the lack of diversity in candidates. Conservatives and hardliners – who already controlled the legislature, the judiciary and the presidency – enjoyed an insurmountable advantage because the Guardian Council barred nearly all prominent reformists and centrists from both races.

Rather than put up a meaningless opposition, some reformists refused to provide a smokescreen for the governing circle. “Reformists cannot participate in meaningless, non-competitive, unfair, and ineffective elections in governing the country,” declared the Reformist Front, an umbrella of political parties and organizations. Three political prisoners – sociologist Saeed Madani, media activist Hosein Razzaq and reformist politician Mostafa Tajzadeh – also boycotted the elections.

In July 2023, Faezeh Hashemi, a former lawmaker and the daughter of former President Hashemi Rafsanjani (1989-1997), had warned reformists against participating in the 2024 election. “Any kind of presence in the upcoming elections is collaboration with lies and hypocrisy,” she wrote in a letter from infamous Evin Prison, where she was serving a sentence for encouraging anti-government protests.

On Jan. 24, 2024, former President Rouhani warned that the council’s “politically biased” rejection of his candidacy for the Assembly of Experts will “undermine the nations’ confidence in the system.” He alleged that the ruling elite was seeking to “reduce public participation in elections ... intending to dictate the people’s fate through their decisions.” On February 19, former President Khatami stopped short of calling for a boycott but said that Iran was “very far from free, participatory, and competitive elections.”

Key Issues for Parliament

Iran’s outgoing parliament faced the COVID-19 pandemic, tightened U.S. sanctions, water and energy shortages, terrorist attacks, the mysterious poisoning of thousands of schoolgirls, and nationwide anti-government protests after Amini’s death in police custody. In 2023, it passed the controversial “hijab and chastity” bill, which increased penalties for women not adhering to the rigid Islamic dress code.

The next parliament will also face a daunting array of challenges, including high inflation and unemployment, international isolation, and growing discontent at home. “The cumulative impact of U.S. sanctions, fluctuating oil prices, mismanagement, and rampant corruption have impacted all strata of society,” Hadi Semati, a former Tehran University professor, told The Iran Primer. “The middle class, once robust, has been shrinking as families struggle to deal with the high cost of living.” Annual inflation stood at 38.4 percent in January 2024.

Key Issues for the Assembly of Experts

The Assembly of Experts has historically served as a rubber stamp. It has never seriously opposed the decisions of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini (1979-1989) or his successor, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (1989-present). The coming election “is important mainly because of the looming succession,” Semati said. The body would be responsible for officially naming Khamenei's successor should he, age 84, die or become unable to fulfill his duties during the eight-year term of the next assembly. The next supreme leader could well come from the body’s ranks.

Iran’s deep state – including the powerful Revolutionary Guards, the Guardian Council, the Assembly of Experts, and the Office of the Supreme Leader – is tightening the “circle of trust” to make sure the succession goes as smoothly as possible, Azodi said. The Guardian Council barred all candidates who might not fall in line with the deep state’s eventual selection. The council rejected former President Rouhani even though he had served on the body for 24 years. It also barred Hassan Khomeini, the reform-leaning grandson and heir apparent of late revolutionary leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

Parliament Facts and Figures

The unicameral Majles has 290 seats for 31 provinces; 285 seats are directly elected and five are reserved for the following minorities:

- One seat for Zoroastrians

- One seat for Jews

- One seat for Assyrian and Chaldean Christians

- One seat for Armenian Christians in the north of the country

- One seat for Armenian Christians in the south of the country

Each seat represents 190,000 Iranians on average. But Semnan Province has one seat for every 123,000 voters. Alborz Province, which includes the city of Karaj, a massive suburb of Tehran, elects one lawmaker for every 493,000 voters.

Iran has more than 240 political parties and associations. Some are local and some are national. But party membership is not disciplined, and Iranians mainly vote along factional lines. Individual candidates can also appear on multiple electoral lists. In parliament, lawmakers do not necessarily follow their party leadership.

Elections are held every four years. In 2024, the campaign period ran from February 22 through February 28. If no candidate for a seat receives at least 25 percent of the vote on March 1, a second round of elections will be held with the two leading candidates. The winner is then determined by a simple majority. More than 61 million Iranians were eligible to vote in the 2024 elections, according to the government.

Vetting Process for Parliamentary Elections

To be approved by the Ministry of Interior, a candidate must:

- Be an Iranian citizen

- Support the Islamic Republic and pledge loyalty to the constitution

- Be a practicing Muslim (except religious minorities candidates)

- Be in good health and between the ages of 30 and 75

- Hold at least a Master’s degree or the equivalent

The registration period for the 2024 elections opened on Oct. 19, 2023. A record number of people – 48,847 – registered using a new online system. About 14 percent of the candidates were women. The Interior Ministry then passed the names of 21,000 candidates who met the basic criteria to the Guardian Council for further vetting.

The Guardian Council approved a record 15,200 candidates after the vetting and appeals process. It barred 26 incumbents and nearly all prominent reformists, but allowed two notable exceptions to run for office. They were Mohammad Baqer Nobakht, a former vice president under Rouhani, and incumbent Massoud Pezeshkian, who has represented the northwestern city of Tabriz since 2008. Before serving in Parliament, Pezeshkian – a heart surgeon – was health minister under Khatami’s reformist government.

After an appeal, the Guardian Council also approved conservative Ali Motahari, a former lawmaker who was barred from the 2020 election. He had served as deputy speaker of Parliament from 2016 to 2019. Although socially conservative, Motahari was controversial for frequently challenging hardliners on issues of political freedoms.

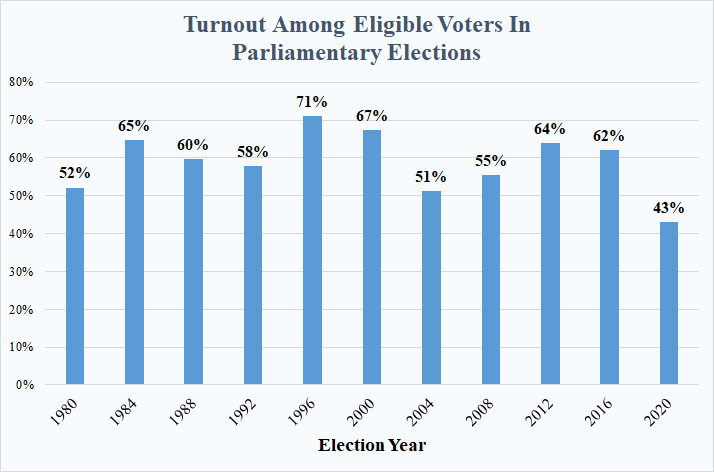

Trends in Turnout for Parliamentary Elections

From 1980 to 2016, turnout for parliamentary elections hovered between 52 percent and 71 percent. But turnout was only 42.6 percent in 2020, the lowest since the 1979 revolution. The turnout in Tehran was a dismal 26 percent. Rather than acknowledge public dissatisfaction, the regime blamed the COVID-19 pandemic. The election came just days after the outbreak of the first cases in Iran.

Supreme Leader Khamenei said that Iran’s “enemies” had exaggerated the threat. “This negative propaganda about the virus began a couple of months ago and grew larger ahead of the election,” he said during a lecture on Feb. 23, 2020. “Their media did not miss the tiniest opportunity for dissuading Iranian voters and resorting to the excuse of disease and the virus.”

Aside from the end of the pandemic, the backdrop for the 2024 election mirrors the 2020 election. In both cases, the elections followed months of internal protests and showdowns with the outside world. Many Iranians were also apathetic after the disqualification of seemingly qualified candidates candidates. And some reformist politicians in Iran called for a boycott of the election. Parliament “has evolved into a largely ceremonial body devoid of those who should originally be its members, namely lawmakers and professionals capable of drafting solid legislation,” Ziabari explained. “In consecutive editions, the Majles has been staffed by ideologues, mandarins and military figures who have risen to its ranks courtesy of their unregulated connections or lavish campaign expenditures.”

Some 68 percent of Iranians were dissatisfied with Parliament, according to a state media poll conducted in July 2023. Furthermore, 53 percent could not name Speaker of Parliament Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf. The results reflected the lack of interest in the body. In January 2024, a newspaper published an Interior Ministry poll that suggested national turnout could be 30 percent, which would be a new low, and just 22 percent in Tehran. A survey by the Iranian Student Polling Agency indicated a turnout of 27.9 percent.

Assembly of Experts Facts and Figures

The body is comprised of 88 clerics and Islamic scholars who are popularly elected every eight years. Members represent provinces, which each have delegations based on population size. The constitution defines the assembly’s tasks to be:

- Select the supreme leader (Article 107 and 111).

- Dismiss him if he is unable to perform his constitutional duties or it becomes known that he did not possess some of the initial qualifications such as “social and political wisdom, prudence, courage, administrative facilities and adequate capability for leadership (Article 111).”

- Supervise the supreme leader’s capabilities to determine whether he is able to perform his duties. The assembly also has a committee to oversee “the continuation of qualifications for the leader specified in the constitution.”

Vetting Process for the Assembly of Experts

From Nov. 6 to Nov. 11, 2023, 510 candidates registered. “Usually, most of the candidates are elderly and conservative clerics who do not have national name recognition,” Semati, the former Tehran University professor, said. The outgoing chairman, Ahmad Jannati, turned 97 in February 2024. To qualify, candidates had to pass written and oral exams on Islamic jurisprudence and exhibit qualities including piety, prudence, political discernment, social perspicacity, and a commitment to justice. The Guardian Council qualified 144 candidates, including President Raisi. It notably barred former President Rouhani, former Intelligence Minister Mahmoud Alavi, former head of IRGC Intelligence Hossein Taeb, and Intelligence Minister Heydar Moslehi.

Trends in Turnout for the Assembly of Experts Elections

The turnout rate for Assembly of Experts elections has wildly fluctuated from as high as 77 percent in 1982 to as low as 37 percent in 1990. In 2009, the government decided to postpone the 2015 election to align it with 2016 parliamentary elections in an attempt to save costs and ensure a decent turnout. The two elections are now paired every eight years.

Photo Credits: Map of Iran's Provinces via Wikimedia Commons (CC by 4.0); Khamenei and Hashemi via Tasnim News Agency (CC BY 4.0);