Garrett Nada

Iran has a numbers problem. Over the past 35 years, Tehran’s family planning policy has gyrated so radically—from encouraging too many babies to producing too few—that the Islamic Republic faces existential economic dangers.

The origin of the problem dates to the 1979 revolution. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini called on women to produce a new Islamic generation for both cultural and security reasons. Khomeini wanted to create a paramilitary force of 20 million religious volunteers to protect Iran from foreign influence. Over the next decade, a baby boom almost doubled the population from 34 to 62 million.

The origin of the problem dates to the 1979 revolution. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini called on women to produce a new Islamic generation for both cultural and security reasons. Khomeini wanted to create a paramilitary force of 20 million religious volunteers to protect Iran from foreign influence. Over the next decade, a baby boom almost doubled the population from 34 to 62 million. But the theocracy, drained by the costs of the 1980-1988 war with Iraq, gradually realized that it could not feed, cloth, house, educate and eventually employ the growing numbers. So with the supreme leader’s approval, Tehran enacted one of the world’s most progressive family planning programs to slow population growth.

The program broke many taboos in a culture that favored large families. Clerics gave sermons on reducing family size, while female volunteers were sent door-to-door to encourage women to have fewer children. New billboards declared, “Fewer Children, Better Life.” Before marriage, couples had to take family planning classes. Health centers dispensed free birth control pills and condoms.

Ironically, the world’s only modern theocracy was home to the only state-supported condom factory in the Middle East, which reportedly produced 45 million condoms a year in 30 different shapes, colors and flavors by 2006. The United Nations and population organizations cited Iran’s program as a model for the Islamic world and developing nations. The United Nations bestowed awards on Iranian practitioners three times from 1999 to 2011.

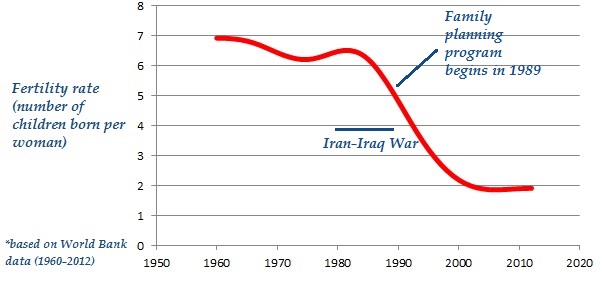

The program worked. The fertility rate plummeted—from 5.5 births per woman in 1988 to about 2.22 births in 2000.

But the initiative was almost too successful. By 2006, the birthrate dropped to 1.9 births per woman—below replacement rate. As a result, Iran’s population is aging. The average age is now 28.3 years. It is expected to increase to 37 years by 2030, according to a U.N. projection. An increasingly elderly and dependent population would heavily tax public infrastructure and social services.

But the initiative was almost too successful. By 2006, the birthrate dropped to 1.9 births per woman—below replacement rate. As a result, Iran’s population is aging. The average age is now 28.3 years. It is expected to increase to 37 years by 2030, according to a U.N. projection. An increasingly elderly and dependent population would heavily tax public infrastructure and social services. Last year, the government began debating steps to prevent the kind of population crisis facing Japan, where sales of adult diapers are expected to exceed baby diapers this year. So far, however, the executive and legislative branches have not agreed on how to raise the birthrate. Some lawmakers want to criminalize permanent forms of birth control, while health officials and experts favor creating government incentives for couples to have more children.

The trend towards having small families may be difficult to reverse, especially without improvement in Iran’s struggling economy. The costs of getting married, let alone having children, are prohibitive for many youth, almost one quarter of whom are unemployed.

In 2010, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad tried to reverse the trend with new financial rewards. Every newborn was to receive a $950 award deposited into a government bank account, with another $95 added annually until the age of 18. The idea was that children could withdraw funds at age 20 for education, marriage, health and housing expenses. But the initiative was halted during its first year of implementation due to lack of funds and coordination across government institutions.

Khamenei’s Call to Action

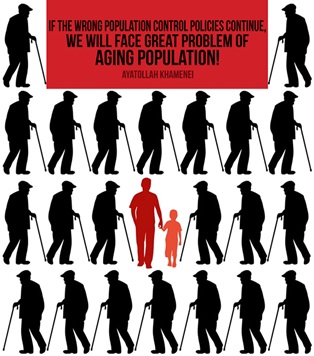

The government introduced more substantive changes in 2012, after Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei said the family planning program had been “wrong” and “one of the mistakes” of the 1990s. “Government officials were wrong on this matter, and I, too, had a part. May God and history forgive us,” he said. “If we move forward like this, we will be a country of elderly people in a not-too-distant future,” he warned.

Khamenei urged the government to introduce measures to boost the population—now almost 80 million — to 150 million or more. The Ministry of Health then pulled funding from the family planning program and ended free vasectomies to encourage larger families. It eventually replaced birth control classes with ones that urged having more children.

In late 2013, billboards depicting happy-looking families with four children were plastered across Tehran. Single fathers with one son were shown lagging behind larger families propelling canoes or bicycles. In 2013 and 2014, Khamenei’s office turned to social media to promoted idyllic visions of marriage and life in large families.

In the spring of 2014, Khamenei began pushing even harder for an increase in Iran’s fertility rate. “A country without a young population is tantamount to a country without creativity, progress, excitement and enthusiasm,” he warned on May 5, which is International Midwives’ Day. Two weeks later, he issued a 14-point decree in letters to the heads of the legislative, judicial and executive branches as well as the Assembly of Experts. Key points included:

· Removing barriers to marriage,

· Encouraging marrying at an earlier age,

· Dedicating new facilities for pregnant and breastfeeding women,

· Providing insurance coverage for childbirth,

· Treatment for male and female infertility

Government Response

Since Khamenei’s decree, the government has reportedly added new incentives, which include lengthening maternity leave, ensuring female job security after childbirth, and subsidizing hospital care. In June, parliament debated controversial legislation aimed at criminalizing male and female sterilization. The bill, approved by 143 out of 231 members of parliament in August, must be reviewed by the Guardian Council to determine its compatibility with Islam.

But the bill has produced a backlash from health officials and women’s groups. Mohammad Esmail Motlagh, a senior health official, argued that the legislation would violate citizens’ rights. He instead called on lawmakers to use voluntary incentives to encourage couples to have more children.

Reformists particularly fear major changes to the family program could negatively impact women’s status, especially in the workplace, where they are already underrepresented. Some 60 percent of university students are female, but only about 12 percent of the workforce, according to the Statistical Center of Iran. Vice President for Women and Family Affairs, Shahindokht Molaverdi, noted that no other country has ever used punitive measures to increase fertility rates. She also warned that outlawing surgical procedures could push contraceptive services underground.

The new policies may also be a hard sell, given changes in society over the past two decades—partly due to the smaller average family size, urbanization and spread of higher education, especially among women. In 2014, the government heralded Qassem Ali-Loui on state television as a national hero for having the country’s largest family—19 children. But nearly 70 percent of Iran’s population is urban and therefore unlikely to see the family’s pastoral lifestyle in Western Azerbaijan province as relevant or inspiring.

Dream comes true for Iranian largest family #Iran http://t.co/KEY0BrRc7Z pic.twitter.com/krgk52BM0C

— Iran (@Iran) January 27, 2014Garrett Nada is the assistant editor of The Iran Primer at USIP.

Online news media are welcome to republish original blog postings from this website in full, with a citation and link back to The Iran Primer website (www.iranprimer.com) as the original source. Any edits must be authorized by the author. Permission to reprint excerpts from The Iran Primer book should be directed to permissions@usip.org