Robin Wright

They’re the determinators—the politically savvy, socially sassy, and media astute young of Iran. And they count, quite literally, as never before as a new president takes over.

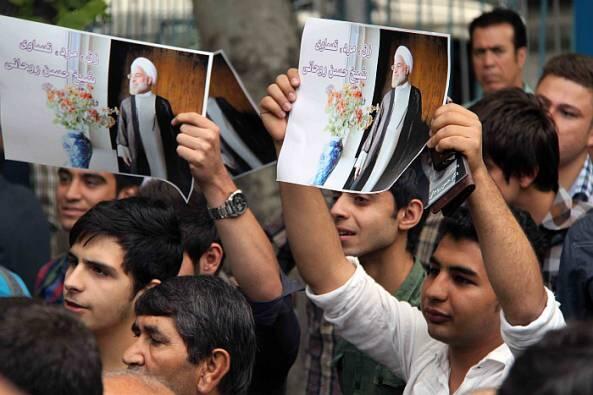

President Hassan Rouhani owes his election to the young, who are Iran’s largest voting bloc. At the last minute, vast numbers opted to back him rather than boycott the poll. They’re also now the centrist cleric’s biggest headache, as he has to meet their expectations. Two-thirds of Iran’s 75 million people are under 35—and they vote again in four years.

President Hassan Rouhani owes his election to the young, who are Iran’s largest voting bloc. At the last minute, vast numbers opted to back him rather than boycott the poll. They’re also now the centrist cleric’s biggest headache, as he has to meet their expectations. Two-thirds of Iran’s 75 million people are under 35—and they vote again in four years. But the Islamic Republic’s long-term survival may also be determined by the first post-revolution generation, born in the 1980s and now coming of age. For Iran’s baby boomers reflect the regime’s almost existential conundrum—and the nexus between economic and nuclear policies.

To be credible, the world’s only modern theocracy must better the lives of its struggling young majority. And to jumpstart the economy, Tehran will have to compromise with the outside world on its controversial nuclear program to get punitive international sanctions lifted. It’s a huge—but increasingly inescapable—price to pay for keeping the determinators on board.

The regime has limited time to act. Iran’s young are antsy because they are better educated and more skilled than any earlier generation. Literacy has almost doubled since the revolution—to over 95 percent, even among females. Iran won a U.N. award for closing the gender gap.

Yet one of the theocracy’s biggest successes has proven to be one of its greatest vulnerabilities. It can’t absorb the post-revolution babies.

Iran’s young face rampant unemployment, estimated officially at up to 30 percent but unofficially at up to 50 percent. During his first appearance at parliament, Iran’s new president acknowledged in June that 4 million university graduates were jobless—and a mushrooming problem.

Iran’s young face rampant unemployment, estimated officially at up to 30 percent but unofficially at up to 50 percent. During his first appearance at parliament, Iran’s new president acknowledged in June that 4 million university graduates were jobless—and a mushrooming problem. The core economic issue has had a rippling effect. In a country where the median age is 27, vast numbers can’t afford to marry or move out of their parents’ homes. One-third of females and one-half of all males between 20 and 34 are now unmarried, according to the Statistical Center of Iran.

Frustration is reflected in soaring drug use. The State Welfare Organization reported this year that almost 72 percent of Iran’s drug addicts are between 18 and 25.

Born after both the monarchy and the revolution, the young often refer to themselves as the lost generation because they have little to do and even less to inspire them. Revolutionary leader Ayatollah Khomeini died when they were in diapers. And most were tots during the traumatic eight-year war with Iraq, which produced more than 1 million casualties in the 1980s. The conflict shaped the goals, fears and nationalism of their parents and the current political leadership.

But for the young, the war is relegated to history—and the now fading public billboards of the previous generation’s war “martyrs.”

Sixty percent of Iran’s young now say the Islamic Republic needs to adopt new ways of thinking to secure its future, according to an Intermedia Young Publics survey released in May. One-third of those polled between the ages of 16 and 25 said they would abandon Iran if given the option.

The implications can’t be overstated. Iran’s post-revolution generation is the largest baby boom in Iran’s 5,000-year history. Its influence will only grow due to one of the world’s most unique population bumps.

Iran’s twenty-somethings were born during a decade-long blip in between two ambitious family planning programs. The shah promoted birth control during his final decade. By the end of the 1970s, 37 percent of women practiced family planning.

After the 1979 revolution, the ruling clerics reversed course and called on Iranian women to breed, breed, breed an Islamic generation. And they did. The population almost doubled from 34 to 62 million in about a decade.

But the theocracy soon realized that it couldn’t feed, cloth, house, educate or eventually employ those swelling numbers—and voters. So it launched a novel (and free) birth control program, including required family planning classes for newlyweds. By the 1990s, the average family fell from six children to less than two—lower than during the monarchy.

Iran’s 70 percent drop was “one of the most rapid and pronounced fertility declines ever recorded in human history,” according to Nicholas Eberstadt of the American Enterprise Institute. The birth rate plummeted so far that former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad warned in 2010 that Iran would be stuck with a “dangerous” aging population in another 30 years.

By actuarial standards, Iran’s baby boomers will have disproportionate clout for at least the next half century on most aspects of Iranian life. Politically, their impact could even be more enduring than the current ruling theocrats. They’ve already shown demonstrated in many forms how far they’re willing to go.

By actuarial standards, Iran’s baby boomers will have disproportionate clout for at least the next half century on most aspects of Iranian life. Politically, their impact could even be more enduring than the current ruling theocrats. They’ve already shown demonstrated in many forms how far they’re willing to go. In 2009, students led eight months of Green Movement protests after the disputed presidential reelection of former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. They mobilized millions in cities across Iran during the “Where My Vote?” campaign, the largest challenge to the regime since the 1979 revolution.

The determinators may no longer be able to protest on the streets. But can make or break politicians. Their interest and energy turned the 2013 presidential campaign around in the final days, boosting Rouhani to a surprise, come-from-behind victory over five other candidates.

Their voices resonate across Iran in other ways too. As the region’s largest network of bloggers, they boldly diss on their revolution, daring to post criticism, jibes, jokes and political cartoons on banned social media through circuitous routes.

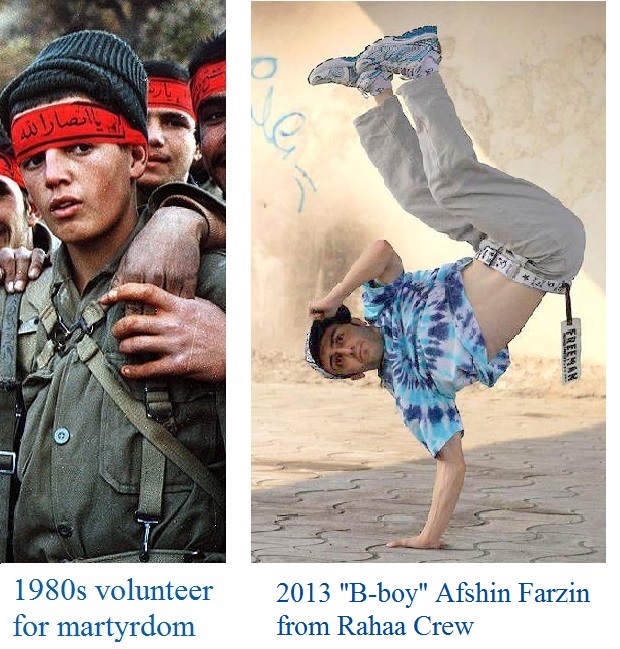

They’re increasingly creating an alternative culture, pushing boundaries further than any time since the 1979 revolution. The stereotype of their parents’ generation was a black-shrouded woman or a young man sporting a headband that vowed martyrdom for Islam.

Images of the young today are more likely to be mall-hopping, increasingly in flashier fashions that defy conservative Islamic dress. Or they may be at play, including performing parkour, a holistic sport that combines running, climbing, swinging, vaulting, jumping and rolling that resembles open-air gymnastics but in public places.

In a telling sign of changing times, Iran’s young have even popularized rap as the rhythm of dissent in the world’s only modern theocracy. They hold back little in their warnings to the regime, as Yas, Iran’s leading hip-hop artist, rapped defiantly,

“Listen to my words and see the agonies I suffered

What my generation has seen, made our tears fall

Those without such pains—how they saw ours,

They became even more cruel, what a pity for our land!”

Robin Wright has traveled to Iran dozens of times since 1973. She has covered several elections, including the 2009 presidential vote. She is the author of several books on Iran, including "The Last Great Revolution: Turmoil and transformation in Iran" and "The Iran Primer: Power, Politics and US Policy." She is a joint scholar at USIP and the Woodrow Wilson Center.

This piece first appeared on www.foreignpolicy.com

Photo credits: Afshin Farzin from Rahaa Crew via Facebook, Basij volunteer via Wikimedia Commons, @HassanRouhani via Twitter, Hijab-3 by Pooyan Tabatabaei via Flickr, Isfahan University graduates by gire_3pich2005 (Own work) [FAL] via Wikimedia Commons, Coralin Design